This story comes through a content-sharing partnership with Wyoming Public Media.

Wyoming is talking about the greater sage grouse again: a polarizing topic that has been in conversation amongst western states over the last couple of decades. The federal government wants to expand the bird’s protected range, and the state is skeptical about that plan. So, state officials and locals recently put their heads together about it to craft their own plan.

How did we get here?

Every spring, male sage grouse perform a mating ritual where they strut around and flare their chest to create a unique air popping sound. They only do the ritual on what they consider sacred mating grounds, which are called leks. There are over 1,000 in Wyoming. Once a group of sage grouse picks a lek, they will return time and time again.

“Because that’s what they know,” said Linda Baker, executive director of the Upper Green River Alliance. “And that’s where they feel comfortable. And that’s where they find what they need to have a healthy, happy life.”

But once the leks are disturbed, sage grouse will not always return, as they are not very adaptable. Their habitat – big, wide open sagebrush landscapes – is popular for ranching, energy development and even the occasional wildfire. And all of those things can cause the bird to not return and not breed.

“Once it’s gone, it’s gone,” said Baker.

Today, best estimates show that sage grouse populations have declined by 80 percent since the 1960s – putting the current day population under half a million.

The bird is not listed as an endangered species. Instead, Wyoming stepped up and figured out their own conservation methods and that kept them from getting listed back in 2015. If they had gotten listed, many say it would have changed how people use the sagebrush landscape across the West. So, Wyoming brought a group of people together and hammered out a way to protect both the leks and the energy economy.

The basis of their plan was the ‘core area’ – land listed as core means it is critical to the bird’s livelihood, so development is limited.

The trouble is, population numbers are still dwindling, so more updates are being proposed.

What can be done?

Recently, a few dozen Pinedale residents gathered to hear about the state’s new sage grouse map. The area is a mecca for both sage grouse and natural gas development.

This time, Wyoming is proposing to add onto the already 15 million acres of protected area.

Bob Budd, executive director of the Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust, has spent years working on the state’s sage grouse management plan. Budd said to the room of people that the state is updating the map because the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is also updating its sage grouse conservation strategy.

“It is a very severe plan compared to what we’re going to talk about today,” Budd said.

From left to right, Bob Budd, Angie Bruce and Randall Luthi explain the state’s sage grouse plan and answer the public’s questions. (Caitlin Tan/WPM)

He said the hope is that, once again, the BLM will adopt Wyoming’s revisions instead.

“Their mapping is based on models based on a whole lot of conjecture,” Budd said. “Whereas what we’re going to show you today is based on actual data, actual birds, actual numbers.”

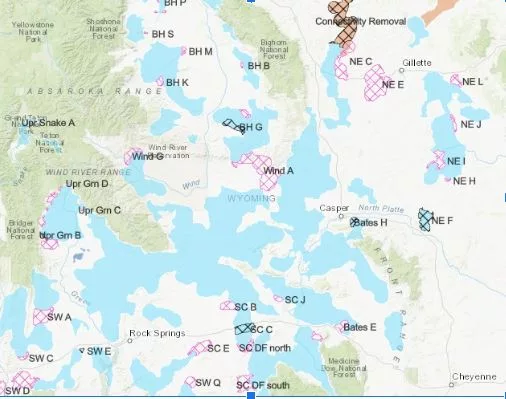

Angie Bruce, deputy director for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, showed the new map to the crowd.

“You can see that pink or red [on the map]. Those are the proposed additions to the core area,” Bruce said.

It looked like little blobs of land tacked onto the already existing protected areas.

“We’re not trying to protect every single acre that they use throughout their entire lifecycle,” she said. “If we did that, a lot of this state would be covered.”

Once land is deemed ‘core,’ only five percent of that area can be developed. There are also restrictions on land use during the grouse’s breeding season – it can limit things like energy development.

Randall Luthi, energy advisor to Wyoming’s Governor Mark Gordon, said that both the bird and development can coexist if managed right.

“Federal Government [should] stay out of it,” Luthi said. “Let the state continue to manage the sage grouse.”

The pink, checkered areas are the additional proposed core areas. The blue is already designated core. (Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

Dylan Bear, a local Pinedale resident who attended the meeting, said he does not think the state’s current sage grouse plan is working. Otherwise, populations wouldn’t keep dropping.

“A lot of those leks are just disappearing,” Bear said. “So as we go with that, I think landowners and industry have a good chance right now to step up and say we want the core areas to expand.”

Other stakeholders

But some groups feel like the state’s current plan offers enough protection. Ryan McConnaughey, vice president of the Petroleum Association of Wyoming, pointed to the mitigation work done by the industry, like decreasing surface disturbance through horizontal drilling.

“Wyoming’s primary economic driver is the oil and gas industry, and we continue to see increased barriers, both financially and things such as these regulatory changes coming with the sage grouse,” he said. “Despite the fact that we continue to see improvements from the industry that mitigate those environmental factors.”

And others feel like even more land needs to be added than what Wyoming is proposing. Linda Baker with the Upper Green River Alliance, said the sage grouse are a keystone species.

“If we’re taking care of the annual cycle of sage grouse year round, then we’re also protecting habitats for mule deer and pronghorn,” she said.

Ultimately, the decision is up to the BLM, but, if Wyoming can negotiate a compromise like it did back in 2015, it might have a say in how sage grouse are managed going forward.

The state will issue its final map to the BLM and the federal plan will likely be released by the end of the year.