Abbi Washakie’s body was found in a dumpster in Riverton, Wyoming in 1989. Her partner had pushed her hard enough to snap her neck and tried to hide his crime.

A member of the Eastern Shoshone tribe, Washakie — who was in her early 30s — is one of countless Indigenous women to meet similar fates, according to Jordan Dresser, who was family friends with Washakie.

“[This story] shows the danger of how things can just escalate so fast,” Dresser said.

Dresser, who chaired the Northern Arapaho Business Council, was heavily influenced by his personal experience seeing Indigenous women fall victim to violent crimes on the Wind River Reservation. So, he spent the last few years co-directing the film, “Who She Is,” which highlights four of the state’s Indigenous women who’ve gone missing or been murdered. This includes Washakie, as well as Sheila Hughes, Jocelyn Watt and Lela C’Hair.

Dresser is clear: This is not just a Wyoming issue. Across the country, murder is the third leading cause of death for Indigenous women, according to the Urban Indian Health Institute. The goal of “Who She Is” is to humanize the women behind those statistics.

The 40-minute animated movie will be screened in Jackson on Wednesday.

“I hope that this film sparks important conversations,” Dresser said. “But most of all, I hope it keeps these women’s memories going.”

An ‘epidemic’

The missing and murdered Indigenous women (MMIW) movement first started gaining steam in 2016, Dresser said, but it’s been an issue since “first contact” between Indigenous peoples and Europeans.

Dresser pointed toward exploitation from newcomers, churches and boarding schools as just some of the reasons behind the high number of cases. These different groups have taken advantage of Indigenous women, who face higher rates of rape and violent crimes than other races in the U.S.

“A person doesn’t wake up and think, ‘I’m going to go missing today,’” Dresser said. “[Are] there different things that have been built up that potentially that person can go missing?”

He added poverty, domestic violence and addiction also play a role.

These cases have been historically undercounted due to a lack of coordination between different levels of law enforcement and gaps in resources on reservations, among other factors. The Wind River Reservation, Dresser said, only has 16 to 18 full-time police officers for its 2.2 million acres.

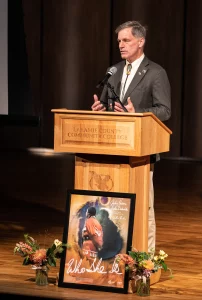

“Who She Is” directors Jordan Dresser and Sophie Barksdale speak at a Sept. 10 screening in Riverton. (Kyle Duba)

According to Dresser, collecting better data would help paint a picture of the severity of the MMIW issue, but that’s not all there is to these women’s stories. “Who She Is” dives into what happened to the women, but also seemingly mundane parts of their lives, such as their favorite colors and hobbies.

Washakie’s story, for example, dives into her relationship with her three children. All of the stories are narrated by family members of the women. Washakie’s is voiced by her granddaughter.

“We felt like it’s a way of keeping their memory alive and almost bringing them back to life,” Dresser said.

State and federal actions

“Who She Is” was funded by the Wyoming Division of Victim Services on behalf of the state’s Missing & Murdered Indigenous Persons Task Force. Gov. Mark Gordon created the task force in 2019, which released its first report two years later.

Gov. Gordon makes opening remarks at the Oct. 5 screening of “Who She Is” in Cheyenne. (Michael Shane Smith)

It found that Indigenous people account for 21% of homicides in Wyoming, even though less than 3% of the population is Indigenous.

This comes as the issue of Indigenous homicides receives more attention on the national level. In 2020, Congress signed into law Savanna’s Act, which aimed to increase coordination between different levels of law enforcement to improve responses to missing and murdered Indigenous persons.

Federal lawmakers also passed the Not Invisible Act in 2020, which established a commission to reduce violent crimes against Indigenous persons. Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland appointed Dresser to the committee, which aims to come up with solutions to combat the issue.

One of those solutions is the Ashanti alert system — which functions like AMBER alerts, but for active cases of missing Indigenous persons, and other at-risk adults. Dresser advocated for incorporating the system in Wyoming, and a bill to introduce it is currently making its way through the state legislature.

Dresser thinks that efforts such as the alert system and the film are a start to addressing the crisis.

“At the end of the day, we’re just trying to get these people who are missing home,” he said, “and also help people make healthier decisions about their lives.”

Event information

“Who She Is” will play at the Center for the Arts at 7 p.m. on Wednesday. The free showing will be followed by a conversation with filmmakers and film participants.