Subscribe to Jackson Unpacked. Available wherever you get your podcasts.

A new healthcare reality set in on Thursday as Congress blocked proposals that could have kept insurance costs lower for marketplace users. Now, Biden-era premium subsidies are all but expected to expire by the end of the year meaning individual premiums could surge by upwards of two-to-three fold.

Wyomingites will face the highest price hikes in the country unless lawmakers can squeeze through a solution with bipartisan support by Jan. 1, according to KFF.

Sadie Frank, a Jackson resident of five years, is one of many caught in the congressional crossfire.

Frank, 28, first followed a wave of newcomers to mountain towns during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. After a yearlong stint working at Jackson restaurants, she landed a job at a small community theater in 2021, too small to offer employee health insurance.

This year, Frank paid $348 a month for Mountain Health Co-Op’s cheapest plan. Should the subsidies expire as expected, her sticker price will start at $676 a month, or nearly double, for the cheapest Blue Cross Blue Shield plan. Gold and Silver plans offer more coverage, but for even more money.

“It’s a huge monthly expense,” Frank said. “I love my job and I think that I’m paid well, but this is an expensive place to live and it doesn’t help.”

For those like Frank who can’t get insurance at work, the Affordable Care Act marketplace offered an option. It also brought down the country’s rate of uninsured to historic lows.

Congress rejected two proposals that could have offered a solution to the surge in prices, or at least a stalemate.

Democrats in the senate had opted for a three-year extension to keep the Affordable Care Act marketplace afloat. Wyoming Sens. John Barrasso and Cynthia Lummis instead supported a GOP-backed proposal to shift federal funds to Health Savings Accounts to eventually allow for an overhaul. Neither responded to KHOL’s request for comment.

Without some sort of subsidy, most marketplace plans could soon be out of reach for working-class Wyomingites, according to Katie Befus at Enroll Wyoming, a nonprofit that helps people navigate the marketplace.

“We have the farmers and the ranchers and the independent business owners and it’s going to have an extremely high impact on them,” Befus said. “It’s going to hit Wyomingites very, very hard.”

With the expiration of the enhanced premium tax credits, she said out-of-pocket premiums have “[gone] up quite a bit, in some instances, upwards of 200%.”

With the co-op leaving Wyoming by the end of the year, Frank, and all other Teton County marketplace consumers only have Blue Cross Blue Shield plans to choose from this year. Much of the rest of the state will, as of this year, have limited access to United plans.

Jackson resident Haley Whittaker, 28, also works at a small nonprofit that doesn’t offer employee health insurance. Her new rate is now $720 a month. That’s more than double her former rate and more than half her rent. She feels like her “hands are tied” and she’s forced into a “lose-lose situation.”

Whittaker already works two part-time jobs — one as an adaptive ski instructor and the other in yoga — on top of a full-time nonprofit job. She’s considering taking on more work or forgoing insurance altogether as a last resort.

“However, I also don’t want to be living with that much insecurity,” she said.

To make ends meet, Frank also plans to take on more side gigs, like bartending.

“What a fool to be cautiously optimistic,” Frank said as the reality of the new cost began to sink in.

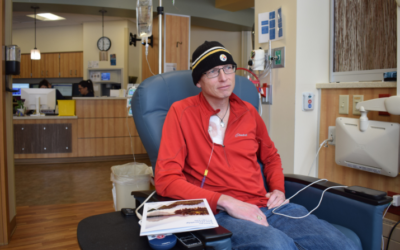

Sadie Frank, 28, checks her premium increases in KHOL’s studio. A near doubling of her monthly costs means Frank will pick up more bartending after her full-time job. (Jenna McMurtry / KHOL)

Both have until January to sign up for a plan to avoid a lapse in coverage.

Even with the option of taking on more work, Dr. Bruce Hayse, is worried that some will still fall through the cracks.

“The Affordable Care Act has been a huge boon for my patients,” the healthcare practitioner of over four decades told KHOL.

His primary concern is the working people of Jackson, whom he said are already struggling to secure reasonable plans. But not having insurance isn’t a good option, either, he said.

“It’s unfortunately a little delusional to think that you can get away without having insurance and nothing bad’s gonna happen,” Hayse said. “That’s faith-based thinking but unfortunately it collides with reality too often.”

In Jackson, that reality means all the risks that come with a lifestyle dominated by activities such as skiing, hiking and climbing.

About a quarter of his patients face more expensive price points on the marketplace, he said.

Hayse expects some to cut back on coverage. Others might visit the doctor less. While that’s not a concern for his office finances, it could be for St. John’s Health, where he sits on the board.

“The hospital’s in somewhat of a difficult situation these days financially, because we are up against some forces that are causing rural hospitals to be in a very economically precarious position,” Hayse said.

Those forces include growing rates of uncompensated care, a loss in federal funding and Wyoming legislators’ plan to slash property taxes even more this spring. Hayse summed it up this way: having a small community hospital in rural America is “not a very financially viable endeavor.”

When patients ask Hayse what to do these days, he doesn’t have an easy answer.

“I can’t say, ‘You should just buck up and spend fifty percent of your income on insurance and the other fifty percent on housing, and you’ll be fine. Go out and go get food from the food bank.’”

That, Hayse said, is “not a nice thing to say to people.”

If Wyomingites want to see change, he thinks it may take pressure on those in power.