Earlier this year, in Montana’s Tendoy Mountains near the Idaho border, a mob of bighorn sheep was released into the wilderness in an attempt to reestablish a herd that previously dominated the range. In video captured by the news site Montana Standard, the sheep sprang out of trucks and onto snow-packed fields, sprinting into a new life.

But the wilderness those sheep and local outdoorsmen enjoy could face numbered days. The Tendoy Mountains are on a shortlist of Western destinations that face potential fossil fuel development after the recent unpausing of Biden’s pause on the federal oil and gas leasing program.

Aaron Weiss is deputy director of the Center for Western Priorities, a public lands advocacy group. When federal parcels are leased by oil and gas companies, he said it means they can’t be preserved in any other way.

“That’s where the rubber really hits the road,” Weiss said. “In the case of oil and gas leasing, these parcels that are leased off for nothing. I mean, less than the cost of a hamburger and are then locked up.”

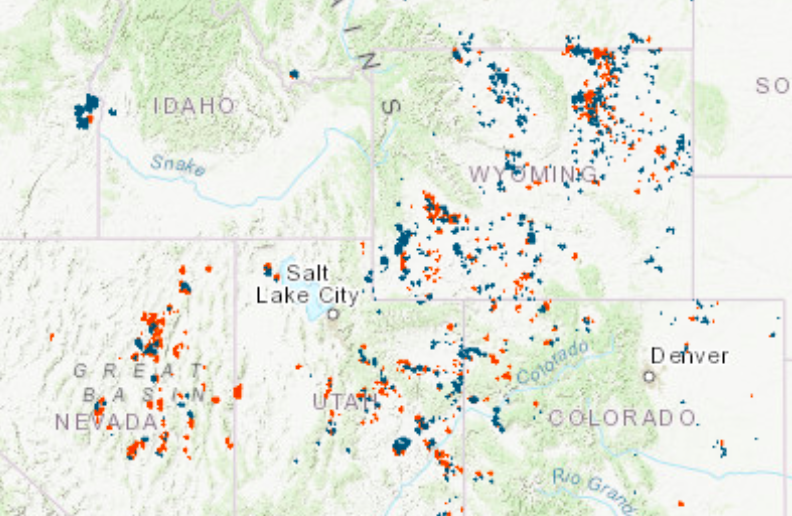

In Wyoming, thousands of acres have already been sold for potential future development, according to a recent mapping project from the Center for Western Priorities.

“Even if all leasing stopped right now—never resumed—you would have a decade or more of production, more or less where it is now, because of everything that the oil and gas industry has already leased and is already sitting on. So, really, it’s a question of what happens to these state economies over the next 10, 20 years. But that is a fundamental question anyway, because of climate change,” Weiss said.

Swaths of public lands in Wyoming have already been scooped up by oil and gas companies for potential future development. (Courtesy of the Center for Western Priorities and the Wilderness Society)

President Biden enacted a moratorium on new oil and gas leases on federal lands within the first few weeks of his administration, citing the need to rein in the fossil fuel industry due to concerns about climate change. But in the months since that decision, local politicians such as Wyoming Gov. Mark Gordon and both of the state’s senators have been extremely critical of the moratorium.

“I want to make clear that the leasing ban is having an impact on the economy and is doing nothing to solve the environmental problems that they’re trying to address,” Gordon said in a press conference last week.

“The oil and natural gas industry supports 11.3 million jobs across the country and contributes nearly $1.7 trillion to the American economy. It makes no sense to send production to other countries when we could be doing it here,” Junior Sen. Cynthia Lummis said in Congress earlier this month.

“Wyoming’s energy has powered this nation for decades. So today, Wyoming and the Mountain West is under attack,” Senior Sen. John Barrasso said in a recent speech.

Not surprisingly, fossil fuel companies have been equally critical. On Aug. 16, the American Petroleum Institute filed a lawsuit against the Biden administration claiming that the federal government is obligated to hold lease sales. State mineral interests have also alleged that 160,000 acres of public lands in Wyoming alone would have gone up for auction last quarter had the moratorium not been in place, which Gov. Gordon argues will cost the state around $6 million.

But Weiss said these companies are crying wolf about the moratorium’s impact.

“It has had zero effect on state economies. Oil and gas companies are sitting on years and years of existing oil and gas leasing and years of already approved permits to drill. So, anyone who says that this leasing pause has caused any effect to state economies is just simply full of it,” he said.

In fact, active drilling rigs increased in Wyoming over the past year, according to Gordon and the Casper Star-Tribune. But a federal judge in Louisiana still ruled back in June that new oil and gas leasing must resume on public lands after yet another lawsuit. The Department of the Interior has said it will appeal the ruling, but in the meantime, some public lands will officially go back up for sale starting this month.

Speculative interests in public lands for potential oil and gas development are rampant across the Mountain West. (Courtesy of the Center for Western Priorities and the Wilderness Society)

“But that is not a process where you can just snap your fingers and lease a couple hundred thousand acres tomorrow. There is a big, long involved process there,” Weiss said. “And with how long these things usually take, it means the first possible oil and gas sales that we could see could be coming up in the fourth quarter of this year.”

Weiss thinks it’s possible that the Louisiana ruling could be reversed in court. But what’s more important, he said, is a fundamental rethinking of the value of our public lands.

“We cannot treat oil and gas development—we cannot treat mining—as the primary desired use of our public lands. There are more important uses of them, including conservation, including hunting and fishing, including recreation,” he said.

A number of bills that would update the federal oil and gas leasing program are currently on the table before Congress, including options that would increase royalty rates for extracted minerals, boost subsidies for renewable energy sources and protect valuable wilderness areas like the Tendoy Mountains. But one thing’s for sure, according to Weiss: the fossil fuel industry hasn’t shown that it’s willing to compromise with politicians or advocacy organizations like his.

“At the end of the day, oil and gas CEOs are responsible to their shareholders and not to their kids and grandkids. We’ve seen no interest in actually being responsible when it comes to fixing the system,” he said.

So, intense legal battles between Biden and fossil fuel companies are going to persist for months, possibly years, to come.

The Department of the Interior announced on Aug. 19 that it’ll review its coal leasing program as well. Whatever comes of this effort will likely have a huge effect on the Northern Rockies, as 85% of coal mined on federal lands comes from the Powder River Basin in Wyoming and Montana. However, the Biden administration has already said a pause on new coal leases, previously put in place under Obama and reversed under Trump, won’t happen on his watch.