Kelsey Ruehling and her team were dressed in waders and boots on Aug. 11, carrying bags full of equipment from their van to Cache Creek, one of the many streams the researchers have been trudging around this summer.

Ruehling is a master’s student at the University of Wyoming studying zoology and physiology. This summer, she—along with fellow students Emma Román and Clara Bouley—is profiling microbial pollution in Teton County’s waterways, and she’s got lots of gadgets to do so.

“So, Clara’s using an ancient but reliable piece of equipment called a flow meter, and it measures the velocity of the stream using electrodes,” Ruehling explained to KHOL on a day out in the field.

Ruehling’s team is collecting many pieces of data as part of their research. There’s stream discharge, the volume of water moving through an area; turbidity, or the cloudiness of the water; and several more. Ruehling said she wants all these numbers in order to get an accurate profile of many of Teton County’s main waterways.

“Every stream is different and has various influences or potential, you know, environmental factors that may be related to bacteria. And so that’s what I’m kind of trying to understand,” Ruehling said.

The main event of course—the part of the project likely to cause controversy throughout Teton County—are the water samples themselves. To collect them, Ruehling’s team is using a long stick with a claw on the end to dip a jar into the middle of the stream.

“We’re going to process for E. coli and we will extract DNA from the water sample to do some microbial source tracking,” Ruehling said.

Ruehling’s been taking fecal samples on private and public land throughout Jackson Hole, and when she leaves in early September, she’ll have everything she needs to start crunching the numbers and doing lab work back in Laramie. Eventually, after checking and rechecking all of her work, Ruehling will develop a report to be presented back to the community outlining the sources of bacteria in local creeks.

“We’ve had a lot of contact with community members that are excited and are really interested in the work that we’re doing and happy that additional data is getting collected,” she said. “And, you know, one of the goals is to try and understand what some of the sources of contamination are. And so I think that that is reassuring to people, that they’ll get something beyond just E. coli counts.”

Most E. coli, as with many microbes, is actually harmless to humans or even good for us. But other strains are bad, according to Dan Leemon of Protect our Waters Jackson Hole, a group that advocates for protecting and restoring water resources in Teton County.

“The primary sources, of course, are well-known,” Leemon said. “And they include wildlife, pet waste, septic systems, wastewater treatment plants and livestock.”

Protect Our Waters JH successfully lobbied in 2020 and 2021 to have the Teton District Board of Health install E. coli warning signs. (Protect Our Waters JH)

Serious strains of E. coli can cause stomach aches or diarrhea in a mild case, or urinary tract infections or pneumonia in severe cases. That’s why Leemon helped lobby to get signs put up around Fish and Flat creeks, which had “impaired” E. coli levels at the beginning of this year, according to the State Department of Environmental Quality and the Teton District Board of Health.

“I don’t think people quite understand the whole issue with E. coli. And that was one of the reasons for getting the signs out there on Fish Creek, was we felt it was so important that people had the information that they needed to make informed choices about recreating in waters that are impacted by E. coli,” Leemon said.

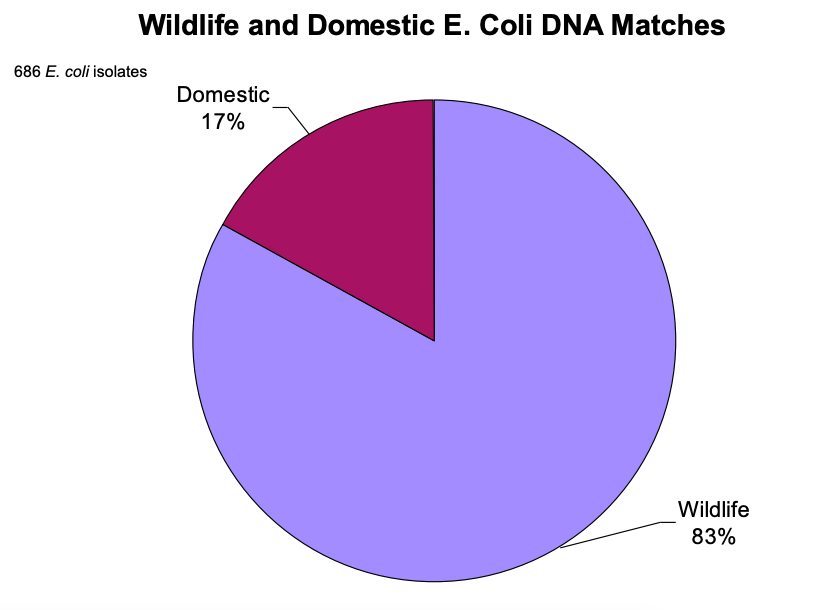

But elevated E. coli levels aren’t always the sole fault of humans, and most microbes found in streams are natural, not from feces. When Teton County’s waterways were last studied on a microbial level in 2003, 83% of the E. coli DNA matches studied came from local wildlife. Just 17% was human-caused. So, Leemon’s looking forward to Reuhling’s report: a much-needed update that will help give water managers a fuller understanding of where to focus their efforts in the future.

“E. coli in wildlife is something we can’t control,” Leemon said. “I hope the community will talk more about the sources that we actually can control.”

Ruehling said she regularly has people come up to her when she’s taking samples to ask what she’s doing and give their thoughts on water quality. Although she wants people to take her results with a grain of salt, she expects to get a lot of local attention once she publishes her findings.

When E. coli was last studied on a microbial level in 2003, it was determined that the majority of fecal bacteria came from local wildlife. (Teton Conservation District)

“Water is, like, incredibly political here in Wyoming. And, yeah, I will say a little bit taken for granted,” Ruehling said. “You know, we think, like, ‘Oh, there’s not that many people here. Like we have, you know, pristine clean water. Like we live right next to the Tetons.’ Yeah, but there’s also thousands of visitors here and there’s, you know, people that may not take as much accountability for what’s going on.”

Ruehling’s research will also build on separate water quality mapping projects released earlier this year on subjects like septic systems and drinking water. Her data will be another piece of the puzzle portraying an issue that’s concerned Teton County residents for decades.