This story is part of a collaboration with Rocky Mountain Community Radio focusing on fossil fuel transitions in the West.

Ann Chambers Noble’s roots run deep in western Wyoming’s Sublette County. She’s owned a cattle ranch for years in Cora, population: 142.

Ann Chambers Noble has written several books and publications on the history of Sublette County. (Courtesy of Ann Chambers Noble)

“My husband and I have descendants of the longest continuous Black Angus herd in the State of Wyoming. It’s 101 years old,” she said.

One of Noble’s many side hustles is being a local writer and historian. And to her, it’s pretty hard to tell the story of Sublette County without mentioning fossil fuels, and in particular, a natural gas boom that occurred in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

“This was the best of times and the worst of times. And it really was that all in the same sentence,” she said.

Geologic discoveries in the area, plus a new pipeline network built all the way to California allowed surveyors to extract massive amounts of natural gas and oil. The local well count exploded from just 58 in 1997 to more than 1,300 only four years later. Noble said nearly every aspect of local life was affected by the boom.*

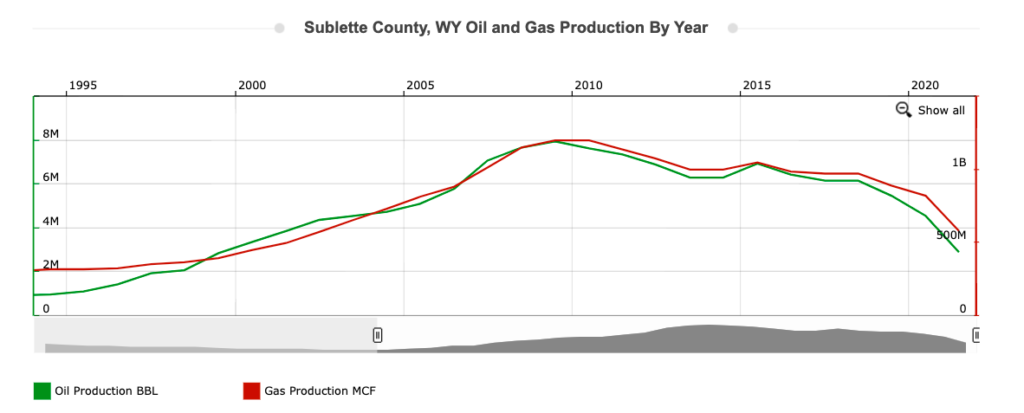

Oil and gas production peaked at the end of the 2000s in Sublette County and has slowly been declining since then. (Screenshot courtesy of DrillingEdge)

“The revenue that was generated was mind-boggling. And it quickly became very addictive. We went from barely being able to pay salaries for teachers to, within a very short amount of time, huge revenues available for our schools,” she said. “We were one of the first schools in the nation that bought every kid a computer.”

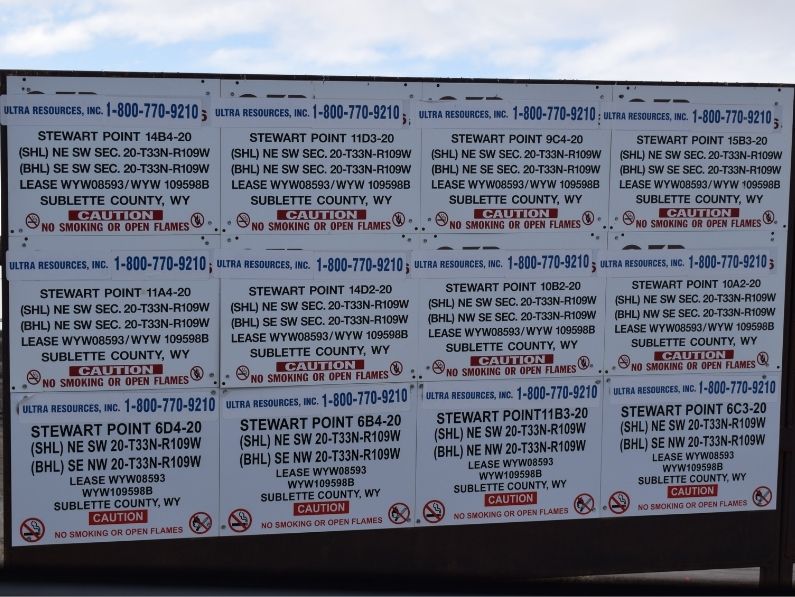

Active oil (green) and natural gas (red) rigs in southern Sublette County. (Screenshot courtesy of MineralAnswers)

But there were also downsides. Noble remembers feeling like all of a sudden she should lock her doors because she didn’t know all her neighbors. Impacts on wildlife and drinking water have also been well-documented.

“The pollution was terrible, and I remember that vividly,” Noble said. “I remember I had high school [age] daughters that we had to decide as parents whether we were going to have them go to ski practice or not. Because the ozone level was so dangerous, it wasn’t safe for them to be exercising outside.”

Ten miles from Noble’s ranch, there are still natural gas rigs dotting the sagebrush landscape over a decade after the boom died down. 80% of the land leased for drilling in Sublette County is federal, and several fossil fuel companies, looking for the next hot spot, think there might be more resources available there.

Steve Degenfelder is land manager for Kirkwood Oil and Gas, based in Casper. He prospects for new mining and drilling spots across the West, where millions of acres are owned by either the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) or U.S. Forest Service.

“Most of the actions that we propose involve the federal government. So, I deal with them on a daily, daily basis. Not just hypothetical,” Degenfelder said.

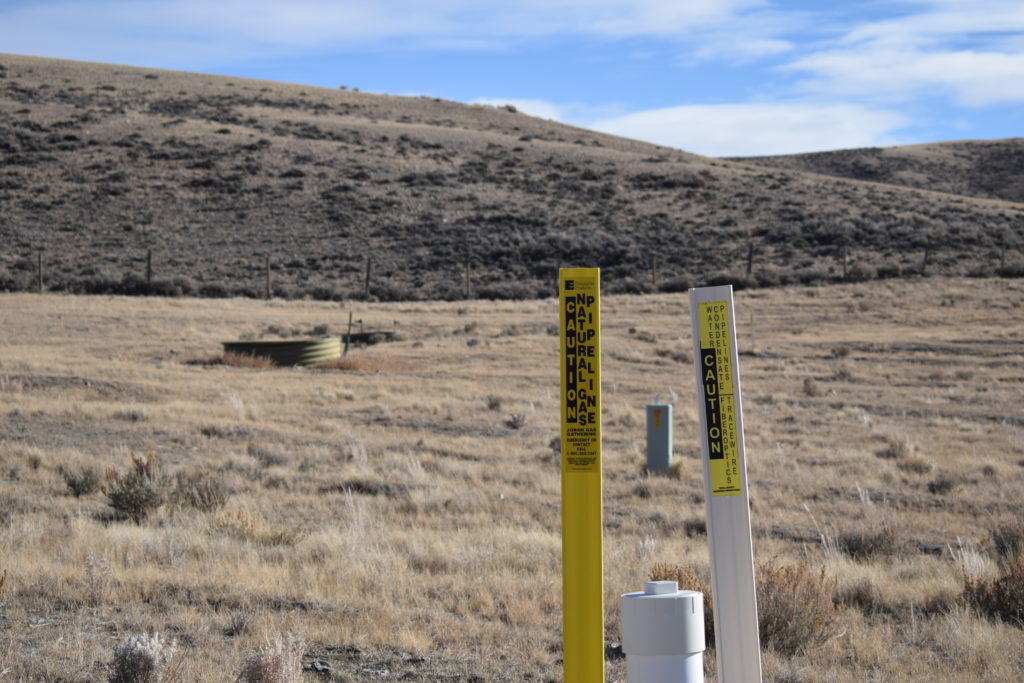

Natural gas infrastructure located on public lands near Pinedale, Wyoming. (Will Walkey/KHOL)

Degenfelder would like to acquire more land in Wyoming to try and spread out his chances of making money. Most oil leases, for example, have just a 5% chance of becoming economically successful. And the more land at once in an area Degenfelder can lease, the more likely it is that he finds a good vein of resources before his competitors do.

“When you’re looking at a geologic base, it’s also offered in such a jigsaw-puzzle type of offering. You might have a prospect that’s a general concept that covers 25,000 acres or more. That might be offered by the BLM in a number of sales over a five-year period,” Degenfelder said. “And so putting that lease picture together is so difficult over a period of years, especially when administrations change.”

Leasing permits issued by the federal government. (Will Walkey/KHOL)

And since the Biden administration came to power, Degenfelder said it’s been difficult to do his job. In early 2021, the U.S. Department of the Interior suspended oil and gas leasing on public land, a decision that was reversed later in the year due to various legal challenges. Leases Degenfelder purchased in a December 2020 sale have also still not been issued, he said.

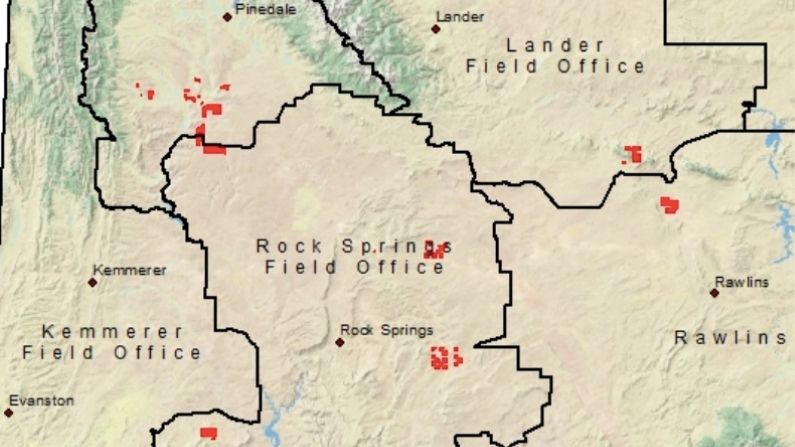

And while a delayed new lease auction is expected in 2022, hundreds of parcels, including many in Sublette County, are no longer on the market because of environmental concerns. Degenfelder disagrees with that policy choice.

“If we’ve made a sizable investment in an area, and we only have 25% of the area covered or leased, and [are] waiting for the BLM to offer the other 75%, you know, we’re in between a rock and a hard place,” he said. “We’ve exposed a bunch of money, but we can’t develop any prospects until we have the lease picture.”

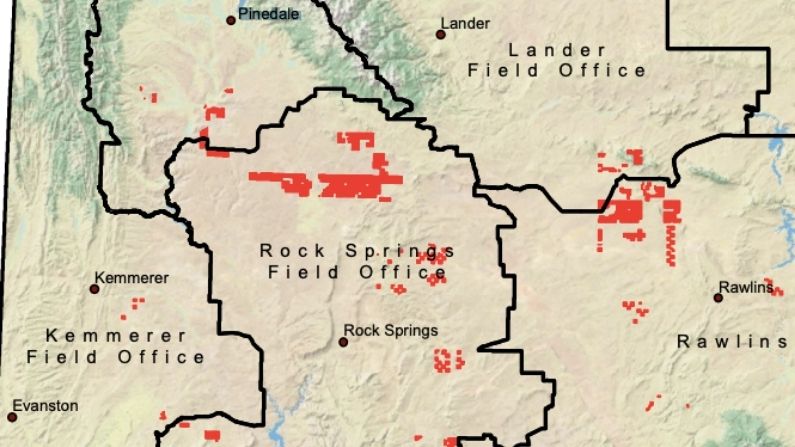

Proposed lease parcels for the 2022 BLM sale in southwestern Wyoming before land was taken off the table. (Screenshot courtesy of the BLM)

Proposed sales after parcels were taken off the table. (Screenshot courtesy of the BLM)

The Interior Department also recently announced that a complete overhaul of the federal oil and gas leasing system, on and off-shore, is in order. Many conservationists are welcoming of the move, including Jesse Prentice-Dunn, policy director for the Center for Western Priorities.

“The laws are 100 years old, and the industry gets to dictate almost every step, from where they want to drill, [to] the low rates they pay to get the leases, [to] the low rates they pay the taxpayers when they drill it, and then the requirements to clean it up,” he said. “And so that’s really what needs to change now.”

Prentice-Dunn argues that Wyoming’s other resources for recreation or renewable energy shouldn’t take a backseat to fossil fuels. He also said that the president’s actions haven’t been that disruptive thus far. In fact, the number of active oil and gas drilling rigs in Wyoming tripled during the leasing pause.

Small bits of pipelines, well pads and other drilling infrastructure frequently dot the open spaces of Sublette County. (Will Walkey/KHOL)

“There are more than 25 million acres of our public lands that are leased for oil and gas, and about half of those are just sitting idle. They’ve got a huge stockpile,” Prentice-Dunn said. “They’ve got thousands of drilling permits that have been approved, but they haven’t used.”

About a quarter of the climate-warming greenhouse gas emissions generated by the United States comes from fossil fuel extraction on federal lands and waters, according to a U.S. Geological Survey report. For that footprint to shrink, Prentice-Dunn advocates that tangible action needs to be taken during the current administration, including charging higher royalty rates for leases and making companies pay for cleanup costs when wells are abandoned. Both laws could incentivize greener business practices from the fossil fuel industry.

“As President Biden has said, we’ve got a code red with our climate. We need to take big action,” Prentice-Dunn said. “It’s absolutely imperative – and I think the administration can do it – to institute some of these reforms. And I think industry also has a big role to play in that, too.”

For now, the leasing system will continue as it has been, with minimal changes despite all the noise and debate on the federal level.

Back at her ranch, Noble said she thinks many locals would welcome future leasing for the jobs, but others are against any new development. Her opinion lands somewhere in the middle.

“I stand to directly benefit from this, so for me to be totally against it would be shooting myself in the foot,” she said. “Come on back. Not to the level you did before. And let’s all stay calm and be responsible.”

Noble also said squabbles over federal land policy can sometimes miss the bigger picture, which is that it’s us humans that need and use energy.

“We are part of the demand. And if we’re part of the demand, we’re enabling that drilling,” Noble said. “They got to get it somewhere. It’s here.”

The question is whether Sublette County will see another drilling boom, or if the country will decide Wyoming’s fossil fuels are better off staying in the ground.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Ann Chambers Noble participated in an extensive oral history project documenting the energy boom of the late 90s and early 2000s in Sublette County. Those resources, including photos and interviews with folks most affected by the boom, can be found here.

(Will Walkey/KHOL)