By Mike Koshmrl, WyoFile.com

GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK—Laura Jones spoke from the grassy flats at the base of Blacktail Butte, a place where Mormon settlers made a go at homesteading the 6,600-foot-high heart of Jackson Hole nearly a century and a half ago.

A vegetation ecologist for the National Park Service, Jones was showcasing Teton Park’s long-running effort to do away with one undesired relic of the homesteading era: non-native smooth brome grasses planted by the cattle-raising newcomers who plowed up this slice of the valley. Park managers are trying to go back to what was, reestablishing the natural sagebrush-steppe plant community that elk, bison and other native species evolved alongside over millennia.

Laura Jones, Grand Teton National Park vegetation ecologist, guides Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff through native sagebrush habitat in Grand Teton National Park in August 2023. (Angus M. Thuermer Jr./WyoFile)

Their task isn’t straightforward or easy.

“There’s no blueprint,” Jones told the Park Service’s regional director, Kate Hammond, and a host of others for a Wyldlife for Tomorrow promotional field trip in late June. “What works? We don’t really know that. Some say, ‘It’s not rocket science — it’s harder.’”

Weeks later, members of Wyoming’s Sage Grouse Implementation Team, who met 70 miles away in Pinedale, spoke confidently about developing a “white paper roadmap” for successful sagebrush restoration. The process, team leader Bob Budd said, starts with ensuring healthy soils, reestablishing perennial flowers and grasses and then waiting patiently for sagebrush and other native shrubs to reemerge.

Bob Budd, who chairs Wyoming’s Sage Grouse Implementation Team, addresses a Sublette County audience during a July 2023 meeting to gather public feedback on sage grouse core area revisions. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

“That will be a game-changer for us, because now we’re looking at areas of the state where we can go in and do restoration,” Budd told residents who gathered for a sage grouse-focused meeting. “I think [the blueprint] is going to be a big step forward for us as far as reclamation and restoration.”

Which is it? Harder than rocket science or a simple process that requires patience? WyoFile asked around and found that land managers in Wyoming have had markedly different experiences attempting to bring back sagebrush-steppe where the embattled ecosystem has been degraded or lost, whether it was from a historic cattle pasture or expansive natural gas fields.

In the uninterrupted sagebrush sea of the Green River Basin, which remains dominated by native species, reviving tracts of sage lost to well pads and other industrial activity has come somewhat easier than it has in Teton Park, where millions of annual visitors potentially fling nonnative seeds from mud caked to their tires. Regardless, it’s unlikely that sagebrush restoration is the silver bullet solution to holding the line of a biome that’s in decline, along with its inhabitants.

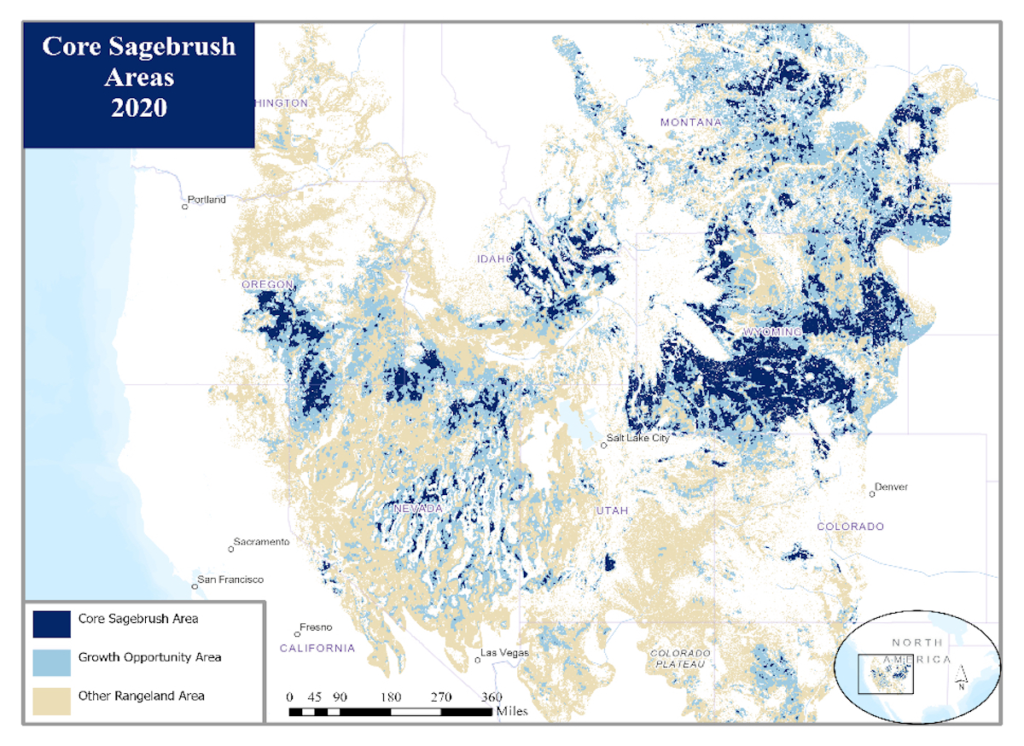

Sagebrush-steppe within 13 western states is disappearing and degrading at a rate of 1.3 million acres a year, recent research has found. There’s no better place to preserve what’s left than Wyoming.

“The core of the biome is Wyoming,” said Matt Cahill, who directs The Nature Conservancy’s sagebrush sea program. “It has the largest, most intact, least disturbed expanse of productive, resilient sagebrush sea, period.”

Sagebrush-dominated landscapes, home to 350 species of conservation concern, are declining in the West at a rate of 1.3 million acres per year. Wyoming is a stronghold for remaining sagebrush. (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Wyoming’s prized, still-uncompromised sagebrush expanse could benefit from more “preventative restoration,” he said. That includes measures like controlling the spread of cheatgrass. “We’ve got to get comfortable with the uncomfortable story of using chemicals to protect biodiversity,” Cahill said.

But Cahill was less convinced that “intensive traditional restoration” — putting seeds in the ground — is so important today in Wyoming on the landscape level. “There isn’t a huge footprint in Wyoming right now that needs those kinds of tools,” he said, “because there aren’t big expanses that are fully degraded.”

Saving unsullied sweeps of sagebrush from development and forces like wildfire is the cornerstone of a widely accepted conservation strategy for the biome, dubbed “Defend the core, grow the core.”

The Teton experience

While Wyoming’s sagebrush range is impressively intact, there are places where the biome was decimated or retreated, like in Grand Teton National Park. Along the eastern edge of the park, roughly 4,500 acres — about 7 square miles — of sagebrush was eliminated and replaced with non-native pasture grass a century or so ago.

Teton Park ecologists have made progress scrubbing out brome and other exotic plants from the Kelly hayfields, as that part of the park is known. But the process has proven costly, long-lasting, labor-intensive and full of ecological wrinkles. Since making hayfield restoration a goal in a 2007 bison and elk management plan, roughly 1,400 acres have been reseeded. That means about a third of the project has been completed some 16 years into the effort, putting it on pace for a half-century completion time.

The fence line separating sagebrush and historic pastureland marks the north end of the state of Wyoming’s school trust parcel in Grand Teton National Park, a tract known as the Kelly Parcel. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

There’s no one reason why Teton Park’s sagebrush restoration efforts have been so slow going. Typically, between 50 and 100 acres are being restored annually. But one constraining factor is the availability of native seeds. There’s no commercial market for buying native forb, grass and shrub seeds, and even if there was, Jones isn’t convinced it’d be wise to bring in seedstock from outside the region.

“We take our seeds, we hand collect it, we grow it out just for us,” Jones said. “It’s expensive.”

Grand Teton National Park harvests by hand the native seed mix used to replant pastureland that’s being slowly converted to native sagebrush-steppe. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

Teton Park does get outside help on the costs. The Wyldife for Tomorrow program — which lets businesses chip in to support environmental causes — has chipped in about $25,000, according to its website. And the Grand Teton National Park Foundation has been a steady supporter, partnering on the project since 2016 and providing nearly $1 million to date, communications manager Maddy Johnson said.

Still, the most recent annual budget for the restoration program eclipsed $350,000, meaning it’s running tens of thousands of dollars per acre to bring sagebrush back in Grand Teton Park.

However slowly, the remnant pastureland is gaining more semblance to what would have otherwise grown there, if not for the cattle-rearing residents of the park’s ghost town, once called Grosvont.

“It’s really difficult to do, but at the same time these fields of brome aren’t going to replace themselves,” said University of Wyoming botany professor Dan Laughlin, who’s experimenting with tilling and other techniques to try to get more sagebrush established.

Where Jones and Laughlin stood at the park’s “Slough South 1” restoration site, brome had been killed off with a herbicide, the ground tilled and the soil subsequently reseeded with the park’s native seed mix.

Oftentimes the first plants that emerge from treated, plowed and seeded hayfields in Grand Teton National Park aren’t the desired species. Instead, non-native plants like prickly lettuce and pennycress can dominate during the early years of sagebrush restoration. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

In places the native species were indeed coming back, but mostly the bare ground was sprouting with non-native plants that weren’t in the Park Service’s seed mix, like prickly lettuce and pennycress. Those “low priority” species aren’t particularly noxious, and they’re largely left to live and even dominate plots in the early years of restoration.

“They’re so interspersed that you’d be hard pressed to treat them,” Jones said. “That would be expected — that you’re going to have these ‘first arrivers.’”

Meanwhile in gas country

The spread of unwanted plants that aren’t in the seed mix has been less of a factor in the Green River basin, a sagebrush sea stronghold where restoration goes hand-in-hand with natural gas extraction.

“We’ve been very successful in the Sublette County gas fields at getting sagebrush reestablished,” said Mike Curran, an ecologist who’s worked with Jonah Energy and other companies on restoration research. “The good thing there is we don’t really have a lot of non-natives in that system to begin with.”

Reclamation teams have had success reestablishing sagebrush on gas pads in the Green River basin, like this site pictured. (Mike Curran)

Curran, who’s studied how insect communities have responded to reclaimed gas pads, said that industry reclamation teams have found success steering early successional plant communities, especially with one native flower called Rocky Mountain bee plant. Those flowers, which thrive in disturbed soil, fade as sagebrush sprouts and matures — which has happened relatively rapidly in places like the Jonah Field’s reclaimed pads, he said.

“We’ll see sagebrush come up in year one, year two, but it’s year three, four, five when you actually see it put on height and mass,” Curran said. “By year seven, eight, we have pretty good stands.”

About 91% of the plant cover in reclaimed swaths of the Jonah Field is taken up by native species, Curran said. Another 8% are non-natives that aren’t particularly concerning, like Russian thistle, he said, and the remaining percent or so are “invasive weeds.”

“So that’s pretty darn good, I think,” Curran said.

Tracts of unbroken sagebrush in the Green River basin, pictured, are part of the core of the biome. Restoration efforts have gone relatively smoothly in areas like Sublette County where non-native species haven’t gained major ground. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

Curran, who’s spearheading the in-the-works restoration white paper for the Wyoming Sage Grouse Implementation Team, is optimistic that sagebrush restoration is a tool that can be deployed widely to help hold the line of a declining ecosystem. About half of the shrubland biome has been eliminated from North America since the European settlement era, and roughly 14 million acres of what remains has been lost in the last quarter century, according to a 2022 multi-agency research report.

“The Green River basin, that is one of the harshest environments in the Lower 48,” Curran said. “We’re getting less than 50 frost-free days a year and 4 to 7 inches of precip on average down in the Jonah [Field]. If we’re able to do it there, I feel like it should be easier to do it in places like Colorado and Nevada, which are at a lower latitude and have longer growing seasons.”

Room for improvement

Wyoming has also been the setting for ongoing experiments intended to optimize sagebrush restoration. Maggie Eshleman, a restoration scientist for The Nature Conservancy’s Wyoming office, has spent years working with the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality and Bureau of Land Management on seed technologies and habitat modifications to improve sagebrush establishment.

“There’s a bunch of areas throughout Wyoming that have been reclaimed, and generally speaking grass comes back pretty well, and sagebrush hasn’t,” Eshleman said. “Are there ways we can make grass less competitive in those areas so that we can get sagebrush to establish?”

Sagebrush seeds are “super small, really weak, and love to fail,” said Cahill, Eshleman’s Nature Conservancy colleague.

And what Eshleman and others are trying to do is give sagebrush seeds a leg up in the race to establish amid grasses and weeds in soils with limited water and nutrients. They are experimenting with packaging small amounts of fertilizer with small amounts of seeds, ideally so that the added nutrients benefit the sagebrush plant and its root systems without stimulating weeds. It worked in the lab, but less so in their field sites: reclaimed mine land in the Gas Hills east of Riverton.

The trouble has been getting sagebrush seeds to emerge from their fertilizer-based pellet encasement: “Sagebrush needs light to germinate, and when they do germinate, they don’t have a lot of push-power to break out of anything,” Eshleman said.

Sagebrush seeds germinated better when seeds were bathed in a thin fertilizer film, she said, but that method couldn’t really deliver enough nutrients to stimulate germination and emergence.

Sagebrush has succesfully matured in one of Grand Teton National Park’s oldest reclamation sites, pictured. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

The latest method being tested uses “fertilizer balls.” Seeds are essentially painted onto the outside, so they don’t have to break out of anything and have access to light. Results are pending: the sagebrush seed-coated balls are going into the soil this fall.

“We’ll have some results next summer when we go on our hands and knees and look at tiny sagebrush seedlings that could be there or not,” Eshleman said. “But it could be that next spring and summer there is a horrible drought and then you don’t have seedlings.”

Then they’ll have to try again.

Whatever Eshleman and her partners devise could someday help improve restoration outcomes in Grand Teton National Park or any number of places in Wyoming. Although Cahill is emphasizing preservation and “preventative restoration” to ensure the persistence of Wyoming sagebrush — the “core of the biome” — he said there are places where more intensive, traditional restoration could play an important role. Sagebrush resources in the Bighorn Basin, for example, are in rough shape and under siege by cheatgrass.

“It looks like Nevada,” Cahill said. “People aren’t necessarily thinking proactively about what is the risk to the rest of the state? What is the risk to Pinedale, or the Bear River valley?

It’s worthwhile, Cahill said, to think about putting seeds in the ground in the “connecting corridors” that bridge and buffer compromised areas like the Bighorn Basin from the sagebrush-steppe biome’s intact core. Potential areas to consider, he said, include the Atlantic Rim and the Owl Creek Mountains.

“You’re going to put a ton of money on a few acres,” Cahill said. “So make sure that those [restoration] acres are just absolutely critical to a much bigger landscape strategy. I think Wyoming has those options in spades.”

Brome grass, treated with a herbicide, stands dead in the Kelly hayfields region of Grand Teton National Park. Next year, the land will be tilled and reseeded with a mix of native species that includes sagebrush. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

WyoFile is an independent nonprofit news organization focused on Wyoming people, places and policy.