Like what you’re reading? Make our newscast part of your daily listening routine. Subscribe on Spotify (or wherever you listen to podcasts).

Just this year, the Jackson/Teton Housing Department opened 111 deed-restricted homes across three projects opened in partnership with private developers.

That number jumps to 165 with the inclusion of multi-unit projects from Jackson Hole Community Housing Trust and Habitat for Humanity of the Greater Teton Area, which aims to serve the least affluent households.

That means 67% of homes opened this year were completed through private partnerships, making the major driver of new housing, according to a presentation hosted by the Community Foundation of Jackson Hole last week.

That’s a hockey-stick increase since 2012, even as borrowing costs have increased.

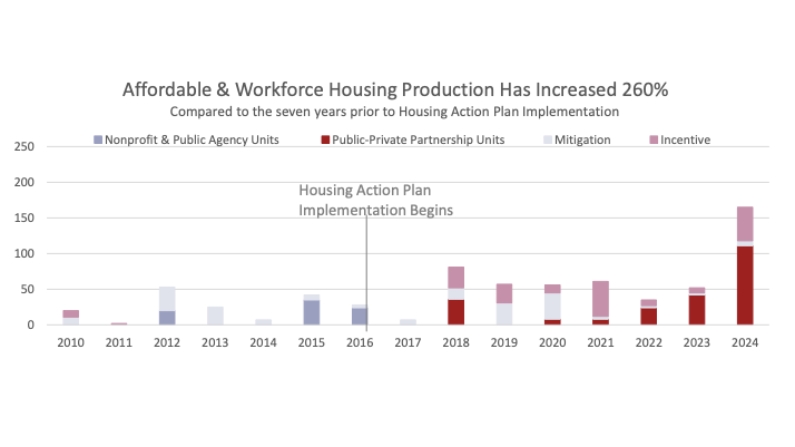

Since shifting to focus on public-private partnerships and incentivizing private sector development of deed-restricted homes, Affordable and Workforce annual housing production has increased 260% compared to the seven years prior. (Jackson / Teton County Housing Department)

“As our costs are going up, and inflation is going up, the project is bigger and bigger, the loans need to be bigger,” developer Tyler Davis said. “I passed on a lot of projects in the last couple of years.”

To build a modest 2-bedroom townhome in Teton County costs about $900,000 dollars. But a household of three earning middle-of-the-road income can afford a sticker price of less than half of that, leaving a “gap” of about $500,000. For rentals, that gap is even greater.

That gap money is cobbled together from many sources. Those include philanthropy, below-market debt, taxpayer funds, and policies like more square feet in exchange for deed-restricted workforce housing.

Joe Rice, who co-owns Blue Collar restaurant group, told the crowd of about 50 that the difference also comes from business owners. Rice is Davis’ father-in-law.

“As an employer, you have to subsidize, that’s the job,” Rice said. “It’s got to be part of your business plan.”

Private partnerships helped get the community out of a stall about a decade ago.

Before 2012, the three organizations that build below-market housing weren’t building enough to keep up with the community’s goals, according to April Norton, director of the Jackson/ Teton County Housing Department. In 2012, the community set the goal of 65% of the workforce to live in the county.

Private partnerships, Norton said, spread the public resources, whether that’s money, or land, or both. To continue the progress, policies always need to be scrutinized, she said, and sometimes tweaked.

Starting in 2025, Electeds are expected to debate the details of that workforce program, created in 2018. Workforce housing is not income-restricted like other affordable housing but still requires most of the household’s income to be earned locally, among other requirements.

A new category of “workforce” housing — serving those who make too much for current models and too little for the market — has become a new policy and will also be under examination.

Though he criticized elected town and county officials for not being in the room through the end of the presentation, Rice also urged electeds to keep the policies that have contributed to workforce projects, such as 30 condos that his son-in-law Davis opened last year.

If the density bonuses are taken away to curb growth, he said, “that will kill housing, maybe, not kill it, but it will hurt it very badly.”