This story comes through a content-sharing partnership with Wyoming Public Radio.

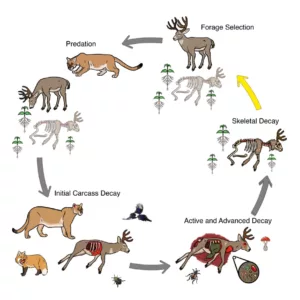

Mountain lions in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem might be actually changing habitat for the better, according to new research from Panthera, a global conservation group that mostly studies wildcats.

Most recently, researchers studied mountain lions in the Tetons, and they found that carcasses from their prey feed a whole ecosystem.

“There is a greater diversity of bird and mammal scavengers feeding on mountain lion kills than any other kind of carrion or meat resource ever documented in the world,” said Mark Elbroch, Panthera Puma program director and lead researcher.

They found that 215 species of beetles feed off the carcasses, but also hundreds of other species of animals.

“Everything from surprising things like flying squirrels, mice, chickadees and woodpeckers to what you might expect, like bears, wolves, vultures and eagles,” Elbroch said.

What sets the lions apart from other carnivores that often dismember the entire kill, is mountain lions leave it intact and only eat about a third, leaving the rest of the kill for other scavengers.

“Pumas contribute over a million kilograms of meat to ecosystems every day, improving the quality of soil and plant life, feeding hundreds of species, and supporting the health of their ecosystems and our planet’s overall web of life,” said Elbroch.

Elbroch fondly refers to mountain lions – or pumas – as ‘ecosystem engineers,’ because they are creating new habitat for species to live in.

“These beetles aren’t there just for food, they’re doing all sorts of other things. They’re using them [carcasses] as little communities to find mates and to hide from predators,” he said. “They’re laying eggs, they’re raising their young, they’re living their lives, on carcasses provided by mountain lions.”

He added that because so much of a mountain lion-kill carcass is left behind, it actually changes the chemistry of the soil – upping the nitrogen composition.

“These carcasses are changing the soil chemistry all around them or under them,” Elbroch said. “And then absolutely, we have strong evidence that the plants are sucking it all up as fast as possible.”

That creates better forage for ungulates, which then creates healthier prey for mountain lions – repeating the whole cycle over and over again.

Elbroch said he hopes the research helps communities appreciate lions – rather than fear them.

“You can hunt mountain lions and conserve them. You can raise sheep, and have mountain lions as neighbors,” he said. “You can have healthy children and have mountain lions in your systems.”

He advocates for ending unlimited hunting of them – and rather having quotas. Some hunt areas in northeast Wyoming have unlimited hunting. About 150 to 200 lions are killed annually in the state.

Elbroch and his colleagues’ research was published in Springer Nature and can be read here.