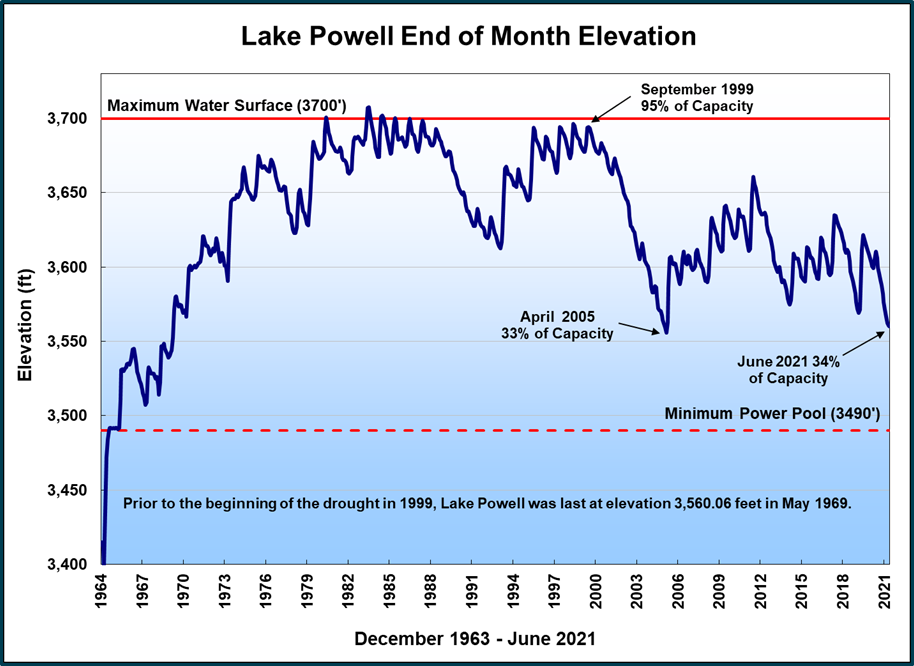

The nation’s second-largest reservoir, Lake Powell, is now at its lowest point since it was filled in the 1960s.

The massive reservoir on the Colorado River hit a new historic low on July 24, dropping below 3,555.1 feet in elevation. The previous low was set in 2005. The last time the reservoir was this low was in 1969, when it first filled. It’s currently at 33% of its capacity.

The popular southwestern recreation hotspot on the Arizona-Utah border, which plays host to houseboats, kayaks and speedboats, has fluctuated over the past 21 years. About 4.4 million people visited Lake Powell in 2019, and spent $427 million in nearby communities, according to the National Park Service.

Demand across the seven U.S. states and two Mexican states that rely on the river hasn’t declined fast enough to match the reduced supply, said Brad Udall, a climate scientist at Colorado State University.

“Basically every drop in the river is being utilized. And so everyone wants a piece of this river and there’s nothing left over,” Udall said.

Some of Udall’s work receives funding from the Walton Family Foundation, which also supports KUNC’s Colorado River coverage.

Forecasts for Lake Powell’s inflows from the Colorado River grew increasingly pessimistic during spring and early summer this year. Flows from April to July are projected to be 25% of the long-term average, placing 2021 into the top three driest on record for the watershed.

Lake Powell is now at its lowest point since it first filled in the late 1960s. (U.S. Bureau of Reclamation)

“The hard lesson we’re learning about climate change is that it’s not a gradual, slow descent to a new state of affairs,” Udall said.

Emergency water releases from smaller reservoirs upstream of Powell will take place over the next six months. They’re meant to maintain hydropower production at Powell’s Glen Canyon Dam.

“I’m very alarmed,” said Tanya Trujillo, assistant secretary for water and science at the U.S. Interior Department. “It’s not only focused on hydropower concerns, we’re concerned operationally in general. We’re acting in coordination with the states about these decisions.”

Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir, also on the Colorado River, is at a record low. Both Powell and Mead are projected to decline further this year. The reservoirs are part of a water delivery system on which more than 40 million people rely.

Lake Mead’s decline will for the first time trigger an official federal shortage declaration.

“The fact that we’ve reached this new record underscores the difficult situation that we’re in,” said Wayne Pullan, Upper Colorado River regional director for the Bureau of Reclamation.

The river’s current managing guidelines are set to expire in 2026. An update to those guidelines passed in 2019 included a potential demand management program in the river’s Upper Basin states of Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico. In its conceptual form, the program would pay water users to voluntarily forgo water deliveries in exchange for payment. The saved water could be banked in Lake Powell to buffer against a potential Colorado River Compact call from downstream states.

None of the Upper Basin states has committed to fully implementing a plan to rein in demands on the river’s water in order to fill Lake Powell with conserved water. The plan remains in an investigatory phase.

“That is one potential solution, or piece of a solution,” said Rebecca Mitchell, Colorado’s representative on the Upper Colorado River Commission. “This has put a sense of urgency in the work that we’re doing at the state level. And we’re going to continue to push forward as much as we can on that.”

This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced by KUNC, and supported by the Walton Family Foundation.