Late Friday evening on the final day of the 2022 legislative budget session, Wyoming lawmakers had done everything they needed to in order to go home, except one thing: Redistricting. It was one of the few legally-required objectives of the session, but still, it was being hashed out by a small committee behind closed doors. For everyone else, what else could you do to pass the time but watch the University of Wyoming play Boise State from the senate chambers?

“I understand they’re going to roll in a screen for a little basketball,” Senate President Dan Dockstader (R-Afton) announced to applause.

With less than two hours to spare before the deadline, the senate managed to pass a redistricting map by just three votes. That ended a more than six-month process featuring countless do-overs of maps and fierce debate. But Sen. Mike Gierau (D-Jackson) said the fights weren’t really about northwestern Wyoming.

“So, for folks in Teton County, I think the whole process worked,” Gierau said. “Unfortunately, I think for the state as a whole, I don’t think it worked as well as it should have.”

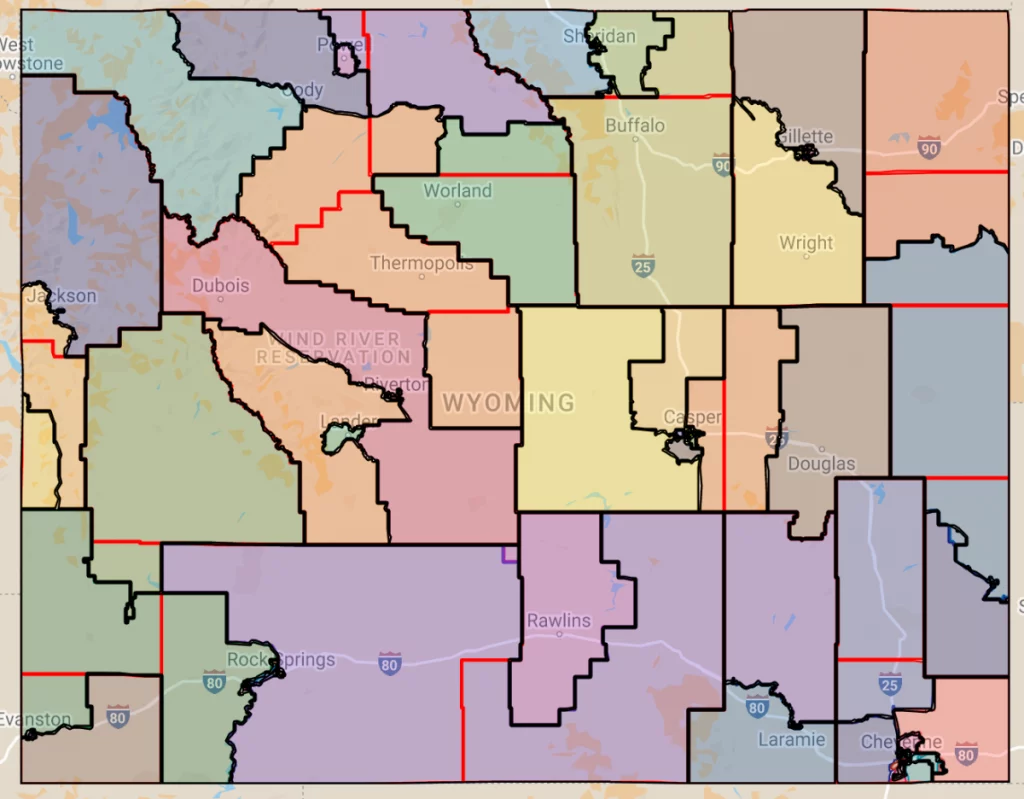

Wyoming’s final map features 62 State House districts, with two out of deviation. Gov. Mark Gordon let the plan go into law without his signature in late March. (Screenshot courtesy of the Wyoming Legislative Service Office)

Gierau voted ‘No’ on the final map, he said, because two districts ended up outside the deviation allowed during redrawing. That deviation rule comes straight from the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which requires that all votes should count equally and each seat should represent about the same amount of people.

In Sheridan and Johnson counties, the lines were drawn in a way that those citizens are actually underrepresented, and Gierau said he believes that could lead to lawsuits, though none have come up yet.

“If someone sues from who lives there and says, ‘Hey, you guys screwed this up,’ I think they stand a good chance of winning,” he said. “Then someone else is going to draw maps. Now a judge is going to draw a map.”

So, why would the legislature create something vulnerable to lawsuits? Well, the process of redistricting may have something to do with it. In the Cowboy State, lawmakers themselves draw the final lines, and Gierau said that can make things messy.

“This redistricting bill was important to every single senator and every single representative in that building. Whenever we talked about it, everybody was eyes front because it was personal. It was about them. It was about their supposed districts,” he said.

In the case of Sheridan and Johnson counties, no lawmakers from the areas were willing to compromise on the final lines, so they went with something that technically breaks the law.

“I mean, literally at one point one senator was talking about, you know, making sure his mother-in-law was in his district. I mean, this is not the way you’re supposed to do this,” Gierau said.

That’s why Gierau and other Jackson area representatives got inspired to look into how other states get redistricting done. And it turns out Wyoming is not the first place to deal with issues like these.

Nicole Borromeo serves as executive vice president of the Alaska Federation of Natives. She’s also one of five members of Alaska’s independent redistricting commission, which was established through a citizen’s vote in 1998.

“Before that, the governor used to draw the districts based on a board that he selected,” Borromeo said. “The citizens of Alaska wanted to make it as fair and equal representation as possible. So, we moved to an independent citizen’s commission.”

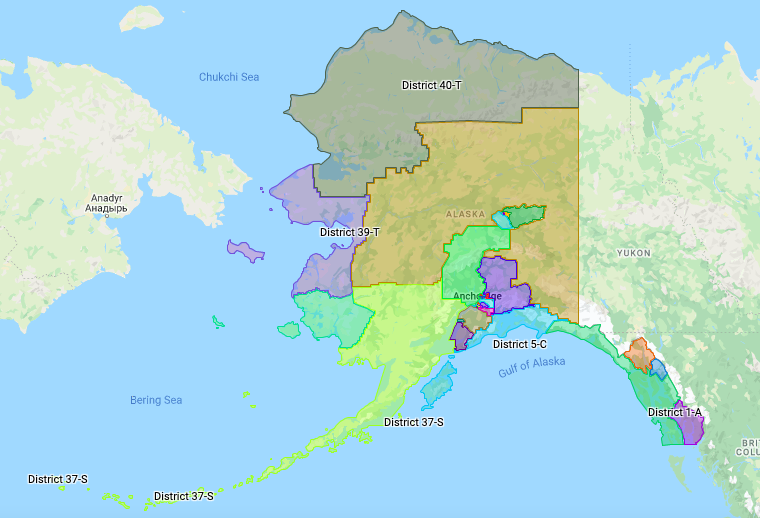

Alaska’s redistricting commission was tasked with the daunting task of drawing a fair map for what is by far the largest state in the U.S. (Screenshot courtesy of the Alaska Redistricting Commission)

Borromeo is a nonpartisan voter who currently lives in Anchorage but has worked all over the last frontier. In her role, she attended 23 public hearings and spent more than 300 hours working with mapping software to present a final map within deviation this year.

“My goals were very simple: I wanted a fair and equal map that represented all Alaskans in a way that we could be proud of,” Borromeo said. “I didn’t want to turn the process over to the courts.”

The way Alaska’s board works isn’t devoid of party politics. The governor appoints two members to the board, the senate and house speakers each make one choice, and the chief justice of the state supreme court makes the final pick. But, Borromeo said, together, board members are able to see the bigger, complicated picture.

“It’s like a maddening game of whack-a-mole,” Borromeo said, describing the challenge of creating a map for a complicated rural state within deviation. “When you take in a certain Census block, it skews the population. And now that district is underpopulated or overpopulated, so you’re borrowing from the district next door to make it within the permissible deviation. So, it’s a difficult charge for sure.”

Gierau said he thinks an independent commission would be able to find compromises more easily in Wyoming. But when he tried to introduce an Alaska-style redistricting bill onto the floor, it failed quickly. Speaking during a meeting on March 8, Sen. Dave Kinskey (R-Sheridan) explained his opposition.

“I just cannot imagine any expert that is going to understand my district like I do,” he said. “And so, I’m just loath to turn it loose to somebody to start drawing lines that doesn’t really understand my people.”

Alaska’s process also isn’t without its problems. The state’s supreme court has already asked them to redraw lines in one gerrymandering case. But in general, independent commissions can create fairer, more competitive voting districts compared to their counterparts, according to The New York Times and FiveThirtyEight. That’s especially true when members are independently selected, mapping criteria are clearly defined and commissions are larger.

The most critical thing to Borromeo is that the public knows what’s happening throughout the process. There are no last-minute changes, and representatives and senators are treated just like every other citizen of Alaska.

“I’d encourage more states to move to what we’re doing in Alaska,” Borromeo said. “And I think that as voters become engaged in the process and learn about redistricting, that they’ll follow it, and some of those human nature aspects and misusing [of] power will be dealt with under the microscope of public scrutiny.”

Now that a new map is drawn for Wyoming, Gierau said other issues are likely to take precedence in future lawmaking sessions. But he hopes this year’s tumultuous process will convince lawmakers to change the way things are done before the next Census in 2030.