Crouched down in the snow on a brilliantly sunny March afternoon in Grand Teton National Park, David Linares put on snowshoes for the very first time.

“SoCal,” Linares said, when asked where he’s from. “So, we seldom get snow up there,” he added with a laugh.

Linares is the first-generation son of Mexican immigrants. This summer, he’ll be trading balmy southern California for the Montana backcountry as an intern at Glacier National Park through NPS Academy–a program aimed at diversifying the workforce of the National Park Service.

“I found out about the academy through an ad on social media,” Linares said. “I’ve always wanted to get into conservation. I just knew that the park service was probably one of the best ways to get into it.”

The majority of this year’s NPS Academy participants raised their hands when asked if it would be their first time snowshoeing. (Skylar White/KHOL)

Now in its 12th year, NPS Academy is a paid program available to 18-30-year-olds from backgrounds that have been historically underrepresented in the park service. Julie Gonzalez is the community engagement coordinator at Grand Teton National Park and an alumna of the academy who helped coordinate this year’s orientation.

“The goal of the program is not necessarily employment, but rather to just create connections with marginalized communities or underrepresented communities in our country to their National Park Service sites,” said Gonzalez, who is also a first-generation Mexican-American.

The academy does that by recruiting a diverse group of participants–18 this year–who get a week of training over spring break and then go on to summer internships at parks across the country. This year’s host parks include Mount Rainier in Washington, Acadia National Park in Maine and Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado, along with Grand Teton and Glacier.

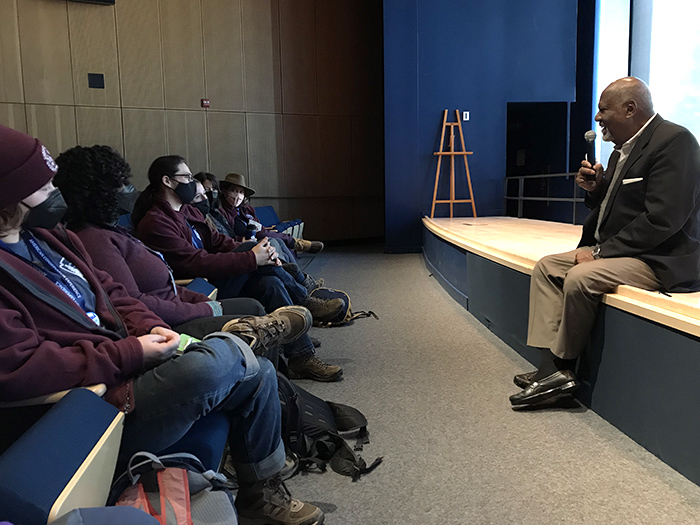

The day KHOL visited the orientation kicked off with an address by Bob Stanton, who served as director of the National Park Service from 1997-2001 and was the agency’s first African American leader. Stanton began his nearly 40-year career with the park service as a seasonal ranger at Grand Teton in 1962.

“It is very, very delightful to be with you here in my home park,” Stanton told the participants. “You honor us with your presence. I know that easily you could have been with your university or college colleagues on the beaches of Florida [or] at Trunk Bay Beach in the U.S. Virgin Islands National Park… or in your dorm room, completing the report that was due last month,” he joked.

Former NPS Director Bob Stanton answers questions from NPS Academy participants at the Craig Thomas Discovery and Visitor Center at Grand Teton National Park on Tuesday, March 22. (Kyle S. Mackie/KHOL)

But Stanton also spoke seriously about spending the first 24 years of his life living in Texas under the immoral doctrine of “Separate but Equal” and about how both his life and the National Park Service changed in the aftermath of the 1954 Supreme Court ruling Brown v. Board of Education, which at least partially outlawed segregation in public education. He also praised former Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall for starting to recruit African American park rangers–including Stanton himself–ahead of the 1964 Civil Rights Act “based on his own courage and commitment.”

Stanton also conceded that the park service still has work to do in order to fully engage, serve and reflect in its workforce the “broad spectrum of the American public.”

Angelina Pius from Lexington, Kentucky, is one of this year’s academy participants who identifies as Black or African American. She’ll be working with Jenny Lake backcountry rangers at Grand Teton this summer.

“It’s really great to be able to have diversity because I think people are more willing to participate in things when they see people that look like them also participating in those things,” Pius said. “And a new, scary experience might be made a little bit less scary if they are with people that maybe are from a similar background or might have been through things that they’ve been through before.”

Diversity also means a lot of different things for the participants. Gabby Thompson of Page, Arizona, identifies as white and as a lesbian.

“When you see somebody that looks like you, that talks like you, or somebody that has their pronoun buttons kind of on their uniform, that really means especially, at least for me, that like queer folks are here,” Thompson said. “[It means] We are present and we are successful and you can embody these careers.”

“I’m, like, a relatively small Asian girl. So, like, you don’t see a lot of that in the park service or at least when I was growing up that’s not something you saw a lot,” said another participant named Marissa Lopez. Lopez is from San Diego, California, and she identifies as a biracial Filipino-American.

“So, yeah, I’m very excited to see not just myself in that position, but [also to] see a lot of my peers doing a lot of the same thing and hopefully just like inspire the next generation as well.”

Julie Gonzalez, left, and Luxianna Watkins, right, are alumnae of the NPS Academy program who now work full-time at Grand Teton National Park and the Grand Teton Association. (Kyle S. Mackie/KHOL)

More than 500 interns have gone through the NPS Academy since it started in 2011–far ahead of the more recent calls for racial justice sparked by the 2020 police killing of George Floyd. And while it’s hard to quantify the program’s success, since employment isn’t the only goal, alumnae like Gonzalez and Luxianna Watkins are proof that the program is helping young people from diverse backgrounds jumpstart careers in the park service.

“The community that this program builds is unlike any other community I’ve ever really been in that has been, like, created by an internship program,” said Watkins, an Asian-American woman originally from Illinois. Being adopted is also an important part of her identity.

As a full-time media associate for the Grand Teton Association, Watkins is putting her educational background in both chemistry and communications to good work. And she said she still keeps in touch with the friends she went through NPS Academy with.

“That’s really useful because as someone who is coming into the workforce in the park service and it’s still majority, like, white, it’s useful to have that community of people that are scattered all over the country who have a shared experience,” she said. “We can talk about NPS Academy and our experiences in the workplace. That support system is built into how this program orients its interns.”

Back outside for the hike, a majority of the group raises their hands when asked if it’s their first time snowshoeing. “I love that!” exclaims a ranger leading the group. And not to worry, she added, getting the snowshoes on will be the hardest part of the whole walk.

KHOL intern Skylar White also contributed reporting to this story.