Every time thick, dark rain clouds move over the deserts that surround Las Vegas, there’s an anticipatory buzz. Flora and fauna alike begin preparing for the rare event, lying in wait for the first few drops.

Todd Esque is usually waiting for them too from his office in Henderson, Nevada. He knows how much desert life depends on their arrival. So when they do come, he’s smiling.

“People will be like, ‘Well, how are things going for you today,” Esque said. “And I’ll say, ‘I’m happy because it rained. Everybody got a drink today.’”

By everybody, Esque means the species of plants and animals he studies as a U.S. Geological Survey research ecologist.

On a cool December day, Esque and his research colleague Felicia Chen ventured out into a study plot south of Las Vegas on the Nevada-California border to check on one of those animals, the desert tortoise.

Few species are equipped to handle a hot and dry climate better than the desert tortoise. The ancient creature inhabits some of the harshest areas of the American Southwest. But with climate change making their home hotter and drier, and energy projects meant to limit carbon emissions springing up in the desert, the tortoises are being hit with a one-two punch.

They’re feeling the effects of climate change itself and bearing the brunt of our efforts to halt it.

The threats to tortoises are many, Esque said, while walking through the sprawling Ivanpah Valley. This stretch of prime tortoise habitat is home to solar farms, a railroad, the interstate highway between Las Vegas and Los Angeles and a few casino resorts. The futuristic-looking Ivanpah solar thermal project—with its rings of mirrors and glowing towers—is within eyeshot of the tortoise study area. A proposed cargo and freight airport is slated to be built in the valley as well.

Tortoises are listed under the Endangered Species Act, and a research plot like this is meant to give researchers insight into the best ways to help their populations rebound and provide scientific findings to decision-makers at the federal, state and local levels.

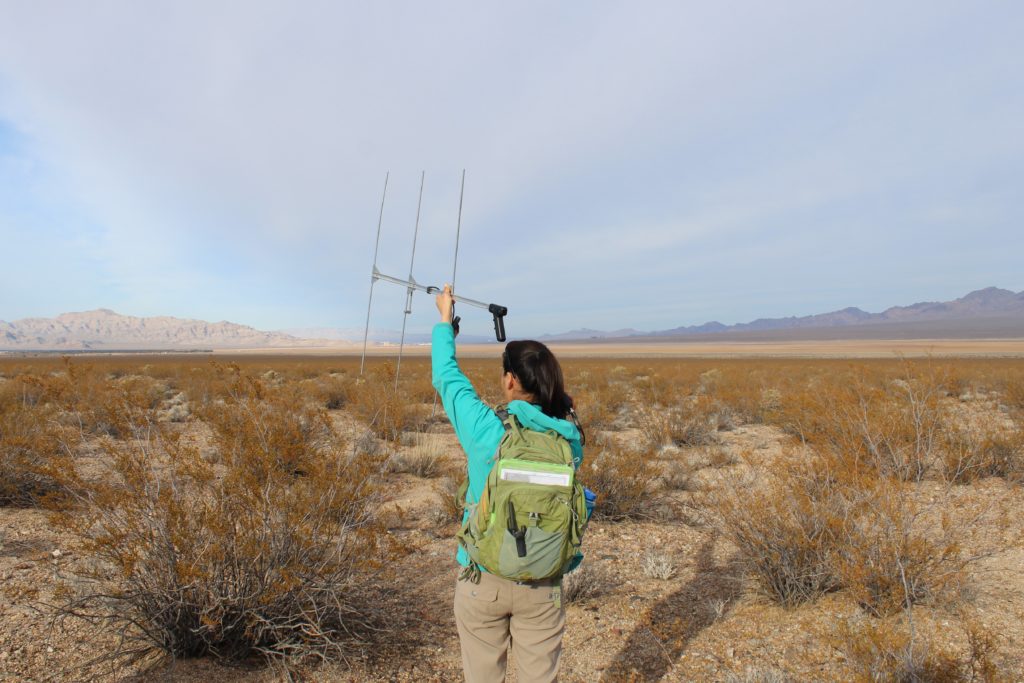

All of the known individual tortoises—25 in this square kilometer—are tagged with radio transmitters. Chen walked through the desert scrub holding a metal antenna in the air to pick up their signal. As she approached burrows with a tagged tortoise inside, the device beeped with increasing frequency.

U.S. Geological Survey biologist Felicia Chen uses a receiver to pick up the frequency of radio-tagged desert tortoises in the Ivanpah Valley. (Luke Runyon/KUNC)

This is how tortoises spend most of their lives, a couple feet under the desert floor. They come out when it rains to drink and in the spring and fall to eat and mate. When cacti are blooming, the tortoises munch on their fuschia-colored flowers, Chen said.

“It looks like they have lipstick on,” she said. “Their mouths will just be stained pink.”

In the study area, researchers have taken the time to mark each burrow. The holes are distinguished from burrows made by other desert wildlife, by their characteristic tortoise shell-shape, like a half moon. In the study area each is marked using a rock with a number etched into it.

“Because these are permanent study plots they all have an address,” Esque said.

“This is like 5679 Tortoise Lane? Something like that?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he said.

Because of where the Ivanpah Valley sits in the Mojave Desert, the area likely acts as a nexus for desert tortoises, Esque said. It’s a place with many entrances and exits, which allows a free flow of genes among the animals that live in other valleys.

“It’s very useful for humans as well as it is for the wildlife, and it has created some conflict in the conservation and development world where there’s people who have had to come together and make agreements on what are we going to allow in these areas.” Esque said.

That’s a short-term challenge for tortoises — figuring out how to keep them from being displaced and their habitat fractured. One strategy is to simply relocate tortoises, temporarily or permanently, to make room for massive solar arrays and other development.

But climate change presents an existential threat for the long term, Esque said.

“If we have hotter temperatures and less rainfall — first of all, they’re not going to get a drink as often. If we just have long droughts, we’re going to start seeing populations blink out in one valley or another,” he said.

Which tortoises have withstood before. They’ve lived on the planet for millions of years, and are incredibly resilient to climate swings. But with human infrastructure blocking their way, it could be close to impossible for tortoises to repopulate parts of the desert devastated by drought now and into the future.

Desert tortoises are listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act, and their survival has been at the heart of a multi-million dollar effort by several federal, state and local agencies. (Luke Runyon/KUNC)

Tortoises have evolved to persevere through water scarcity, Esque says. A third of their body cavity houses an auxiliary bladder, which stores water and waste. Using the bladder as storage, the tortoises can go more than a year without drinking water.

But even they have a breaking point. Short-term droughts in the Southwest over the past 20 years have caused tortoise mortality, Esque said. In the last decade, nearby Las Vegas set new records for hot and dry weather. And studies have shown the likelihood of so-called megadroughts to increase in the coming decades.

The latest review of tortoise population, published in 2018, showed that despite a concerted effort to boost their numbers, declines continue. In four out of five designated recovery areas in southern Nevada, California, Utah and northern Arizona, desert tortoise population densities dropped from 2004 to 2014.

Another climate change-related problem comes from how tortoises reproduce, Esque said. Their sex is assigned based on the incubation temperature of the eggs. Too hot or too cold and you can have a whole set of baby tortoises come out as all male or all female. A warming desert could tip the biological scales.

After more than a mile of wandering, Chen located a burrow with a visible tortoise inside. Esque pulled out a small mirror to direct sunlight into the hole. Under the intense desert sun, it’s more effective than a headlamp or flashlight.

“It works like dynamite,” Esque said. “So I can see back there easily a meter.”

Chen and Esque moved aside some brush so we could get a better look.

“You can see the entire tortoise,” Chen said. “Pretty much the entire side of it.”

The adult tortoise’s shell was lodged into the burrow’s clay walls. Even with all the hubbub on the desert floor, with researchers chatting, shining lights, a journalist peering, and the constant hum of interstate traffic, the tortoise stayed still.

This one likely came out after the last rainfall 10 days before. It was the first rain this stretch of the Mojave had seen in more than 100 days.

“Once you start to learn about them and you see how harsh it is out here in the desert,” Esque said, “your appreciation just keeps growing.”

Because, he said, you get to see what they’re up against.

This story is part of a project covering the Colorado River, produced by KUNC and supported through a Walton Family Foundation grant. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial content.