Smoke from a nearby wildfire filled the sky in Jackson, Wyoming. The billowing smoke coincided with a fall conference on climate.

“Alright, let’s keep this thing moving,” said comedian Rollie Williams, the host of the annual Climate Solutions Summit for mountain towns. “We’ve got a really great presentation now.”

Inside an auditorium with air filters, hundreds of elected leaders and city workers from across the West twiddled their lanyards, awaiting the next kind of surprising speaker.

Benji Backer discusses how to make environmentalism nonpartisan with Anna Robertson, the co-founder of The Cool Down, which she call’s a “mainstream climate brand.” (Hanna Merzbach / Wyoming Public Media)

“Give it up big for the founder and executive chairman of the American Conservation Coalition, Benji Backer,” Williams announced, as the crowd clapped.

Backer, who’s in his mid-20s, entered the stage wearing a bright pink and blue patterned button-down shirt and white sneakers with bumblebee socks.

“I know, having a conservative environmentalist on stage is not always the most comfortable thing in the world,” he said, laughing.

But he has made talking to left-leaning audiences like this a big part of his job running his conservative-minded nonprofit, which advocates for unleashing nuclear energy, cutting government red tape, and making the U.S. dominant in energy production.

“The reality is that we can’t solve environmental challenges without conservatives,” Backer said. “Conservatives have to be at the table, and that’s what I’m dedicating my life to solve.”

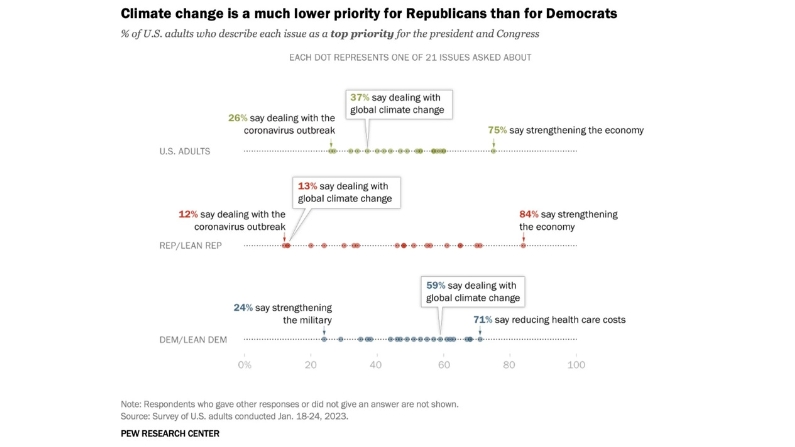

He said conservatives have a long history of caring for the environment. But in a recent Pew Research survey, only 12% of Republicans said dealing with climate change should be a top priority for the U.S. government — compared with 59% of Democrats.

Backer said his work of bringing conservatives to the table all starts with language. He focuses his messaging on four words: nature, stewardship, conservation and environment.

“Each of those four words have one thing in common,” Backer said. “They evoke an emotional connection to the environment itself.”

Backer breaks his own rules by calling himself an environmentalist, since this is his job, but said policymakers don’t have time to change cultures. He said words like “environmentalism,” “eco,” “sustainability,” “climate change” evoke a political response from conservatives, rather than an emotional connection.

Another strategy, Backer said, is focus on shared, local issues that people can feel and see.

“Nobody, conservative or liberal, wants their forests to burn up if they live in that area,” Backer said. “When you talk about polar bears and ice caps and things that are far away … that’s maybe not relevant for everyone.”

Attendees of the conference said they’re already using this technique. That includes Jessica Burley, the sustainability manager for Breckenridge, Colorado.

“For us, it’s a lot of wildfire threat. We have drought. We’re at the headwaters of the Colorado River,” she said. “And so how can we better understand what those are and all come together as a community to say, ‘What does that future look like for us?’”

Jessica Burley, the sustainability manager for Breckenridge, Colorado, stands outside the Center for the Arts in Jackson, where the climate conference happened. (Hanna Merzbach / Wyoming Public Radio)

Andrew Mentzer, the sustainability manager for Blaine County, Idaho, also emphasized rallying people around worsening floods and wildfires.

“I think we can depoliticize a lot of the discussions around climate action by really focusing on that resilience component, that adaptation component,” Mentzer said.

Wrapping up his talk at the summit, Backer said we do also need global climate action, but this isn’t going to happen through one president or congressional act.

“A lot of the cities and towns in this room, they’re doing things in their own ways, and it’s having a global impact,” Backer said. “Even though they’re only doing it at the local level, that stuff does add up.”

From composting to geothermal energy to seemingly mundane zoning rules, local leaders shared their strategies for fighting climate change and promised to be back next year, hopefully to report progress.

This story was produced by the Mountain West News Bureau, a collaboration between Wyoming Public Media, Nevada Public Radio, Boise State Public Radio in Idaho, KUNR in Nevada, KUNC in Colorado and KANW in New Mexico, with support from affiliate stations across the region. Funding for the Mountain West News Bureau is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.