Fran VanHouten started seeking a therapist when she was 18. She first went in college, when she felt like things just weren’t going quite right for her. Now, more than 40 years later, it’s still part of her healthcare routine.

“So, in the same way that I have my regular doctor and my dentist and my doctor, I have a counselor,” she said.

VanHouten has struggled with anxiety and depression for years, including during the two decades she lived in Jackson Hole. She said having a therapist has kept her grounded through transition periods and stressful moments during her career as a life coach and professional facilitator.

“One of the things I notice in me when I think I need a little help is my sleep is disrupted,” she said. “I seem to have a different relationship with food. I’ll notice that my alcohol consumption goes way up and I just seem a little disengaged. I would say I’m watching the world go by rather than participating.”

VanHouten said the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated those symptoms. She lost dozens of clients at work, along with valuable in-person connections with friends and family. So, she started seeking therapy more, and, for the first time, antidepressants.

“I find myself feeling less edgy, and I find myself maybe more responding to humor or rolling with things a little easier rather than having them stick to me,” she said. “If a diabetic needed to be on insulin, nobody would have any second thoughts about that. And I don’t see why this would be any different.”

VanHouten is one of the millions of people in the United States who seek what mental health experts call primary preventative care—regular check-ins that allow people to find solutions to issues on their own.

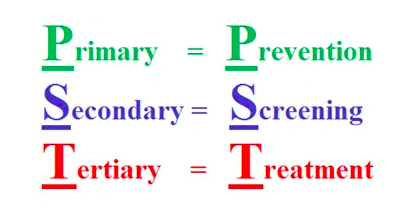

Elizabeth Cheroutes has had a private counseling practice in Jackson for the past 17 years. She said primary prevention is important because it allows counselors to intervene before their patients harm themselves or others. Secondary and tertiary care comes into play when people are missing work, drinking more or even feeling suicidal.

Primary preventative care is used by the most people, but tertiary care is what costs communities the most. (Screenshot/StompOnStep1)

“If you can think of it as a triangle, [tertiary care serves] the smallest population, but it’s the population that costs the most to treat. Hospitalization. Crisis services. Productivity loss in businesses are due to that small population,” Cheroutes said.

Cheroutes also said that since the pandemic started, she’s been seeing more and more people in those more serious, secondary and tertiary situations.

“We’re seeing people with more acute symptoms like headaches, body aches, anger issues, resorting back to substance abuse or suicidal ideation. The pressure has been really great. So, I’m seeing a higher severity, what we call acuity, of people coming through my doors,” she said.

Cheroutes participates in Mental Health JH, which provides 6 free mental health visits to any Teton County resident. Cheroutes said the program, which will end later this month, broke down a lot of barriers for a broad group of people, from teachers to food service workers, who can’t typically afford counseling.

Meagan Murtaugh, a local real estate agent, is one of about 825 community members who sought help from the program over the past 10 months. She also promoted the program on her popular Instagram page, where she highlights the ins and outs of mountain town living.

View this post on Instagram

“Therapy over the years teaches you how to help yourself,” she said. “I still get, like, severely triggered by things. And instead of having to wait to call and talk to my therapist, I now have the tools of like, ‘Okay, if I can sit down and do a meditation and talk to myself like my therapist would talk to me,’ I can calm myself down.”

As the child of an alcoholic, Murtaugh has struggled with anxiety and depression for decades. She’s also been in therapy on and off for about 17 years, but she said Mental Health JH made meeting a counselor easier for herself and many of her friends.

“I feel like people who have started doing therapy on Zoom, they’re like, ‘Oh, this is great. I can talk from my couch.’ And I feel like I’m talking to someone in my home and it’s a little bit less scary,” Murtaugh said.

Meagan Murtagh has been seeing counselors on and off for over 17 years. She works as a real estate agent in Jackson Hole. (Emily Cohen/KHOL)

A locally-run option for teletherapy, though, won’t be as easy to come by starting May 31. That’s when Mental Health JH will stop accepting applications from new patients and start the process of ending its services, partially due to declining funds. Diedre Ashley is executive director of the Jackson Hole Community Counseling Center, and she said her state funding has been systematically cut over the past 15 years.

“Our agency has gone from being about 60 to 65% reliant on the state contracts for our overall budget to now we’re at 30%,” Ashley said. “So, we have to sort of augment it with other areas. Our private donations have had to increase.”

Like Cheroutes, Ashley said she’s seen demand for counseling increase dramatically during the pandemic. But at the same time, Governor Mark Gordon recently recommended a 9% budget cut for the Wyoming Department of Health. For the counseling center, that’ll cost about $75,000, or about the salary of one therapist.

“The needs across the board are rising and getting to the point where these funding sources are having to prioritize,” Ashley said. “And the concern is that providing resources all in one bucket may leave some people out.”

So, who’s being left out? For the most part, the counselors KHOL interviewed say it’s people seeking early prevention care who can’t afford it themselves. A bill signed during the recent state legislative session will limit state funding for mental health and substance abuse services to just a handful of priority groups, like those in the criminal justice system or people living with severe debilitations.

That means Ashley may have to start turning some clients away if they aren’t a part of that narrow, high-risk population. And that puts pressure on the entire human services sector in Teton County, including private practitioners like Cheroutes.

“I don’t want to sound alarmist at all, but this is a really serious situation,” she said. “It means we as private providers are getting referrals for clients who may need a higher level of care than we can provide.”

Cheroutes said she understands the budget constraints on the state level, but that this funding decision will actually cost Wyoming money in the long run.

“For every dollar spent on prevention services, there’s a three- to five-dollar return on the investment,” she said. “For those out there who really look at the numbers, it’s more profitable to invest in mental health.”

Mental Health JH was partially supported by private donors, of which there are many in Teton County. Cheroutes expects local philanthropy to continue financing similar programs, but she also worries that it’s unsustainable to rely on that funding model.

“We have amazingly generous people in this community, but we can’t rely on donations for the mental health needs of an entire community. That funding from the government is very, very important,” she said.

For now, Cheroutes said anyone interested in counseling should still visit mentalhealthjh.com or talk to a counselor to get to know what their options are. People like Fran VanHouten will keep getting the help they need for the foreseeable, but unknown, future.

“There have been a handful of times in my life when I scared myself,” she said. “And I had never really thought about self-harm, but it was a wake-up call. Like, there was a thought and I was like, ‘I can’t believe my head is going there.’ And because I already had counseling in my life, I was able to call immediately.”

Wyoming has the second-highest suicide rate in the nation, and both Ashley and Cheroutes said reducing stigma and the costs of seeking counseling should be a major goal for the state if it wants to improve on this grim statistic. To them, that means investing in counseling services—not cutting it.

If you or a loved one is experiencing suicidal thoughts or an emotional crisis, help is available 24/7 at the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 800-273-8255. Community members can also still sign up for six free mental health visits through May 31 at a local counseling center through the Mental Health JH initiative.