About twice a week, oil and gas operators in Colorado’s Piceance Basin file “Form 19” also called a Spill/Release Report with the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC). Nine times out of 10, the spilled substance is a form of a hazardous waste byproduct called produced water.

For Oil & Gas industry advocates on Colorado’s Western Slope, it’s well known that business just ain’t what it used to be. Brian Gallagher is principal for a small investment group focused on industrial water and sustainability. He’s also a process engineer who has developed treatment methods for industrial water.

“Just the entire oil and gas economy in the western slope has really taken a big hit,” Gallagher said.

Despite the decline in oil and gas production, he says that even until 2019 he was involved in providing wastewater treatment services in Rifle, a town that sits at the center of a once-booming natural gas industry. Downturn or not, the after-effects of the previous boom are still clear to see.

Spend some time driving around western Garfield County and it’s hard to miss the steel tanks, usually in sets of two or more, many of which act as temporary storage for water that flows back to the surface as a byproduct of oil and gas production. This produced water – or wastewater – is a combination of the millions of gallons used to hydraulically fracture each well, plus water trapped in the rock formations with the oil and natural gas.

Produced water and gas condensate tanks, reinforced with lined steel walls for secondary containment in the event of a spill. Taken on Beaver Creek south of Rifle, Colorado. (Lucas Turner/KDNK)

“Any flowback that comes from drilling operations, it could be from an active well that’s actually being developed and actively fracked, or it can be flowback from a well that’s producing,” Gallagher said.

Produced water is also known as “brine” because it can contain large quantities of salts and minerals. Volatile organic compounds like benzene, naturally occurring radioactive materials and many other unknown chemical additives can also be found in the water.

“It’s heavily regulated, in terms of that you can’t just dump it on the ground. It can’t go into the rivers. It’s a difficult thing to dispose of,” Gallagher said. “There’s a significant volume of it, so in order to make money you need to do something with this waste product, and whether that’s injection or treatment, it’s a significant expense and a huge hassle.”

An open pit for wastewater near Debeque in Mesa County, Colorado. (Lucas Turner/KDNK)

The COGCC’s production database shows that in 2019, operators in the state of Colorado reported producing over 26 billion gallons of wastewater, enough to fill more than 40,000 Olympic swimming pools. At least 40 percent of that water was produced in Rio Blanco and Garfield Counties.

Keeping all that water contained and out of the environment prior to disposal or treatment poses a huge challenge. Untreated produced water is corrosive. Combine that with high mineral contents, and over time, pipelines, tanks, pit liners, and valves degrade, resulting in frequent spills. Other contributing factors include human error, failure to follow procedures, freezing temperatures, and operators facing slim margins employing fewer experienced workers to maintain aging equipment.

In 2019 over 700,000 gallons of produced water spilled in the Piceance Basin.

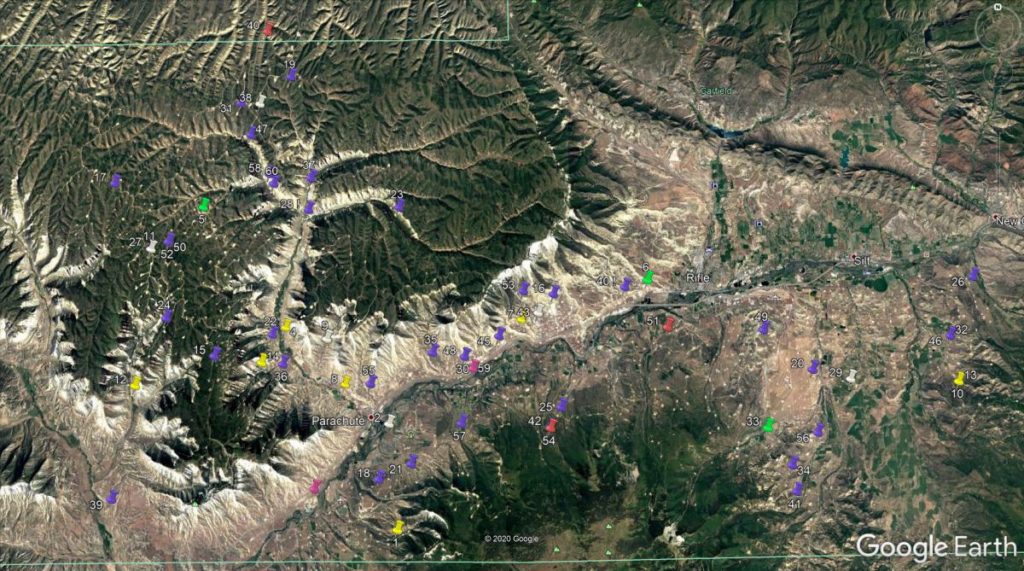

Locations of spills reported to the COGCC in Garfield County in 2019. (Screenshot)

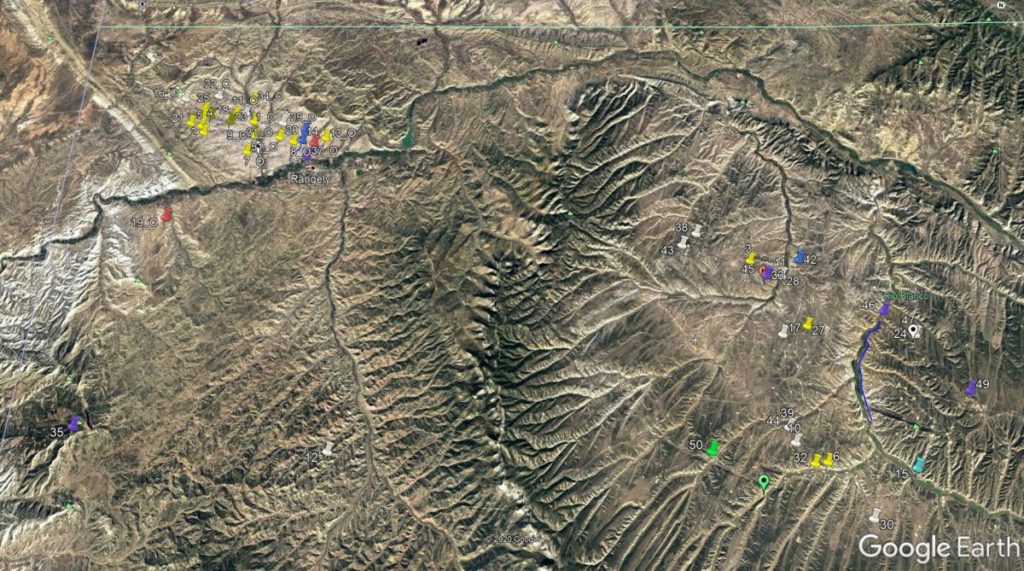

Locations of documented spills in Rio Blanco County, Colorado in 2019. (Screenshot)

In many instances, spills are contained inside secondary emergency containment structures such as piles of gravel or lined steel walls. But operators don’t always get that lucky, and toxic water spills reach the soil, enter surface water, or are discovered bubbling up in the middle of a field above a buried pipeline. Lesley Sebol is a hydrogeologist with the Colorado Geological Survey.

“Sometimes it’ll be contained on top of it. Sometimes it will migrate deeper,” Sebol says. “It depends on what’s down there. And they usually don’t know until they start investigating after the spill.”

Sebol says even spills that impact soil can usually be cleaned up, if they’re spotted fast enough.

“If they catch it right away they will dig out the bulk of it,” she said. “They’ll just go in with excavators and dig it out and oftentimes that material goes to a landfill then afterwards.”

But not all spills are noticed right away, like one in January of 2019, where more than 100,000 gallons of produced water spilled from a ruptured pipeline less than a quarter mile from the Colorado River. Three days later, a buried gas-gathering pipeline ruptured, spilling more than 1000 gallons of produced water and natural gas condensate that made its way to nearby Parachute Creek.

Booms and absorptive pads line an area on Parachute Creek where produced water and gas condensate spilled in January, 2019. (COGCC)

Sebol explains that spills like this can contaminate ground and surface water.

“If it’s enough of a volume and the surface water is close enough, that’s a migration pathway that you would wanna consider,” she said. “If it’s localized and there aren’t any surface water bodies nearby then you’re just looking for downward migration through the soils to the water table.”

An example of a high volume spill that contaminated groundwater happened in 2016 in Rio Blanco County near Bishop Ranch on Piceance Creek. That spill resulted in a 5 million dollar lawsuit and a major fine from the Colorado Oil and Gas Commission. The spill volume is unknown, but four years later crews are still trying to clean it up, with no end in sight.

Producing wells, including storage for wastewater surround livestock north of Parachute Colorado. (Lucas Turner/KDNK)