The release of initial data from the 2020 U.S. Census last week made one thing starkly clear for Wyoming: It’s a regional outlier. The Cowboy State has one of the lowest population growth rates in the country while it’s surrounded by several of the fastest-growing states, including Utah, Idaho and Colorado. But does Wyoming even want to grow?

Marian Orr, the former mayor of Cheyenne, weighed in on Twitter about Wyoming’s low 2.3% growth rate, which ranks 44th in the country, when the first batch of new Census data came out.

Lots of convos re our low growth rate. I learned first-hand as mayor of the largest city in the state – we can’t afford to grow. The avg family of 3 pays $3k/yr in taxes for $30k/yr in gov services from police, fire, schools, roads, etc. And that anti-growth scale is by design. https://t.co/RD8S3TCfIa

— Marian Smith Orr (@gofishwyo) April 27, 2021

“Well, I’ve always said that, to be very frank, I think the state could get out of its own way,” Orr told KHOL in a follow-up interview. “We’ve put some real fences up around attracting certain businesses.”

Orr said she would have loved to bring a casino to Cheyenne during her tenure, but that’s an industry currently restricted to the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming. She also said the state interferes with local control by restricting things like the number of restaurants and liquor licenses available. And then there are constitutional limits on incentives that Wyoming can offer to businesses interested in relocating to the state.

“Our forefathers really, I think, wanted to make sure that, you know, we weren’t, I wouldn’t say overpopulating, but that we were being very cautious with growth,” she said.

Another “elephant in the room” that Orr said is generating revenue in nearby states like Colorado is legalized marijuana, which the Wyoming House of Representatives declined to even debate in March.

“It makes you wonder kind of, ‘Okay, well, then what—what are we going to do?’” she said.

Orr served as a Republican mayor, but Democratic State Representative Mike Yin of Jackson feels similarly about how the state is impeding growth.

“If the policies end up reflecting the idea that Wyoming doesn’t want more people in it, then it means that we don’t want more of anything else in it either,” he said.

Both Yin and Orr also stressed that Wyoming’s slow growth is directly tied to its overreliance on the steadily declining fossil fuel industry.

“We don’t have any other policies to make sure that we can sustain services in the state or facilities or infrastructure in the state long-term,” Yin said. “So, if we can’t build new infrastructure to encourage growth, then essentially we’re saying we’re discouraging growth.”

“If I had a nickel for every time that I heard over my past 30 years in government affairs, you know, about Wyoming’s need to diversify the economy, I’d be a rich woman,” Orr said.

Yin said the core question is: “What does Wyoming really want?” And if the answer is fewer people to share the wide-open spaces with, that comes with consequences.

“It means that you’re not going to have as many opportunities in Wyoming,” he said. “If you grow up here, it means it’s going to be harder to stay here because we have anti-growth policies, right? So, it’ll be easier for you to find some sort of job or work someplace else, especially if you’re interested in starting a family.”

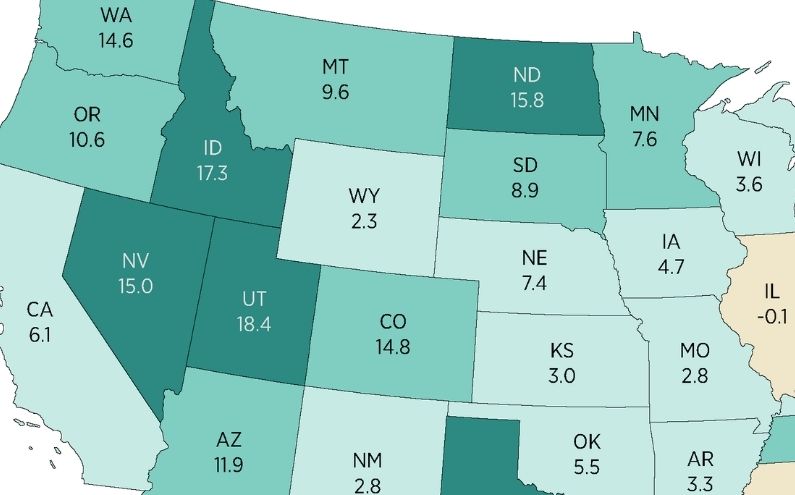

Yin also said it’s clear that other states in the Mountain West are doing better than Wyoming at providing those opportunities while capitalizing on their access to the great outdoors. Utah led the nation between 2010 and 2020 with a population growth rate of 18.4%, and Idaho came in second at 17.3%. Both figures far outstrip the national growth rate of 7.4%.

Will Frohlich, the mayor of Victor, Idaho, said that didn’t surprise him.

“I think Idaho is appealing for a lot of reasons, you know, the connected [sic] to nature, the beauty that it has. Teton Valley, Idaho, and the people that come through here, they’re blown away,” Frohlich said. “You get a lot of really creative people to move here. Our restaurants are amazing. Our small businesses, our entrepreneurship is all there. You have all these really interesting, talented people trying to figure out their way.”

But with rapid growth also comes challenges. Victor, like Jackson, is facing such an intense housing crisis that Frohlich said even the City is having trouble hiring new employees. The mayor also said he worries about how to preserve Victor’s small-town vibe that helps attract people there in the first place.

“’Do you want Victor to grow?’ is a very, uh, tricky question. You know, when I moved here, we didn’t have a stoplight. We didn’t have a lot of the stuff we have now,” Frohlich said. “I don’t think the question is, ‘Do you want Victor to grow? It’s ‘How do you want it to grow?’ Growth is inevitable at this point.”

Yet another tricky subject for the whole “Wydaho” region is the influx of remote workers during the pandemic. Both Frohlich and Yin said they’re not necessarily opposed to that kind of growth, but that they want to make sure the newcomers become part of the community and don’t just exploit it.

Yin also said the more detailed state-level Census data will provide a better picture of what’s happening here locally. That information is expected to be published by mid-August, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.