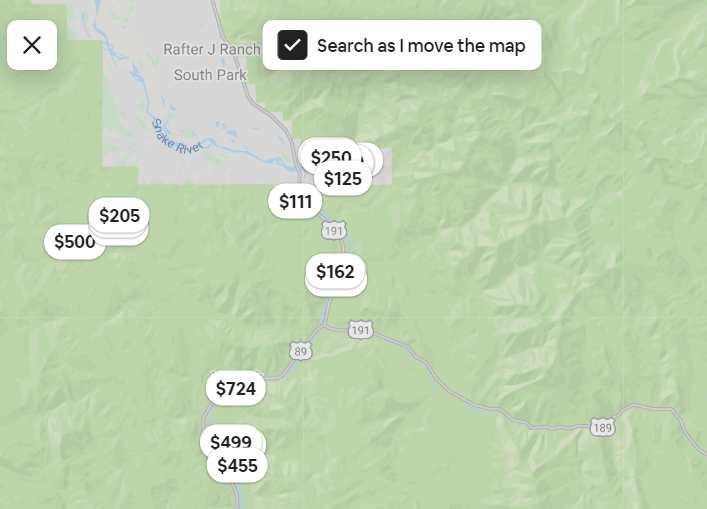

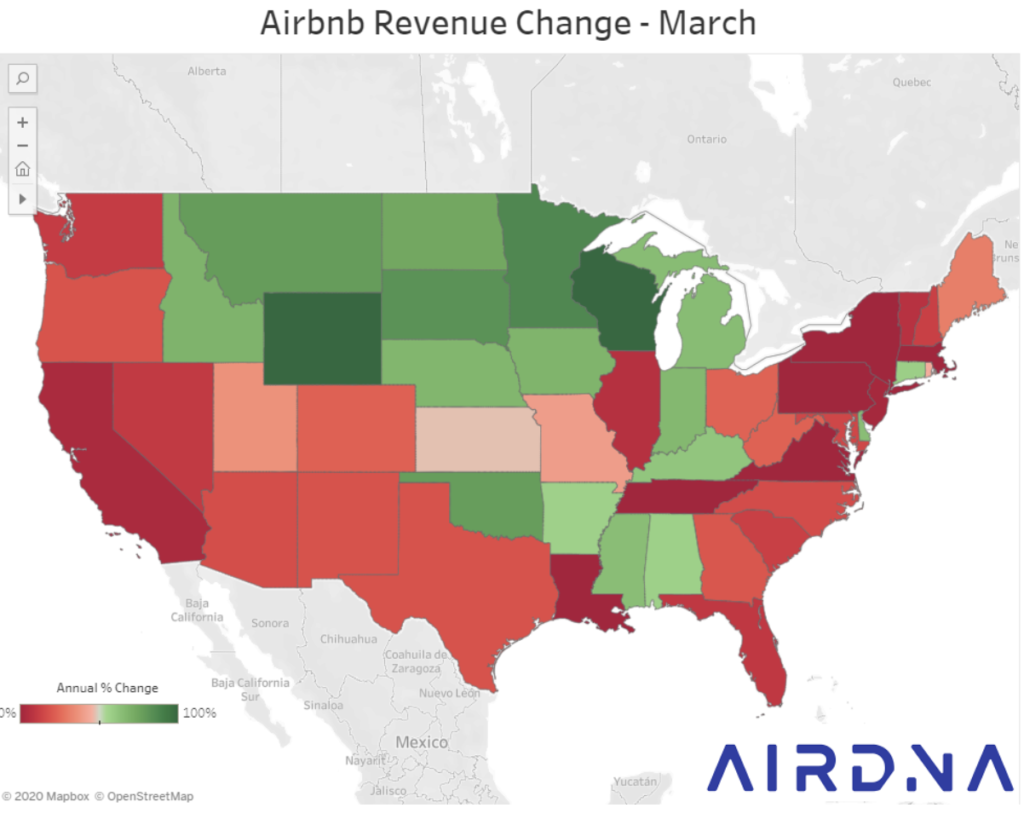

If you try to book an Airbnb vacation rental in the Tetons, you’ll be greeted with a message urging you to check travel restrictions. “Travel only if it’s essential” it reads. But under that warning, available properties still abound. And according to the rental data website Air DNA, Wyoming’s March Airbnb revenue increased 100% compared to last year. Some of that jump is likely attributed to a small increase in supply, but that alone doesn’t explain the boom.

Airbnb rentals in Wyoming saw a huge spike in revenue in March of this year compared to March 2019. (Air DNA)

Many lives in the Tetons are inextricably linked to travel and tourism. Owners and managers of short-term rental properties are no different as they ride the COVID-19 rollercoaster. The ones who agreed to speak with KHOL provided some nuance to the data.

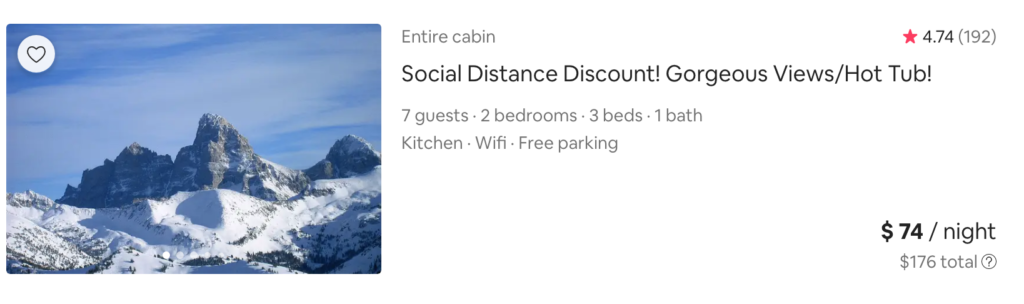

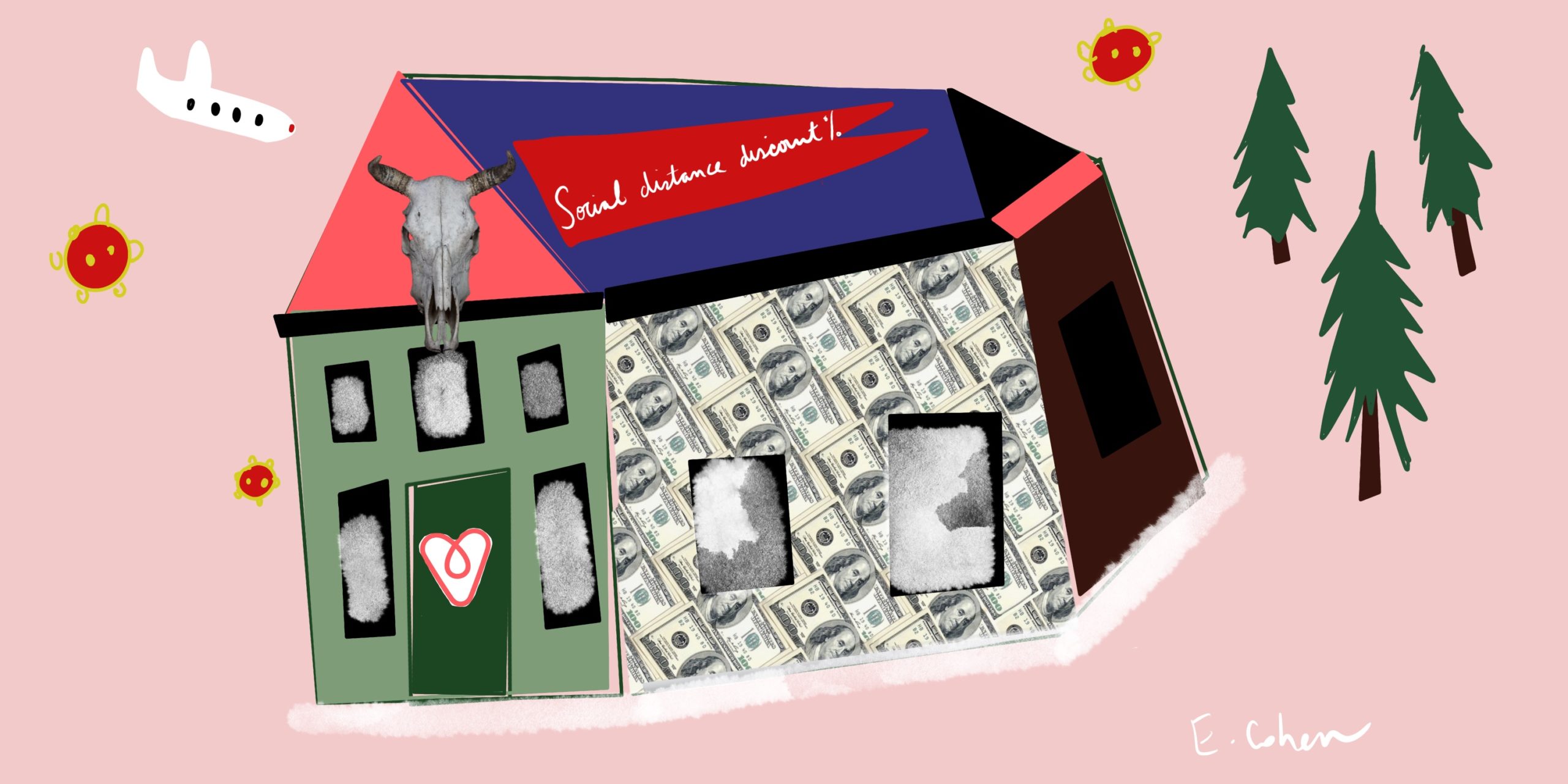

Some saw a brief spike in booking inquiries from tourists trying to flee bigger cities or hoping to keep their trip plans in the face of the pandemic, while others dealt with a wave of cancellations as stay-at-home orders were enacted across the country. Many properties are vacant now. But those that are filled are catering to a wide variety of clientele. There are some owners and managers marketing to travelers wanting to hunker down. An Alta cabin listed on Airbnb boasts a “social distance discount” with “gorgeous views/hot tub!” Another guest house in Teton Village advertises: “Escape the City! Social Distancing Special!”

Some short-term rental owners are encouraging visitors to escape cramped city quarters for Jackson’s wide-open spaces. (Airbnb)

A cabin in Alta, Wyoming, near Grand Targhee Resort, also calls on visitors looking for respite during the pandemic. (Airbnb)

But beds are also being filled, at reduced rates, with seasonal workers in between housing and facing job uncertainty.

‘An Abundance of Caution’

Reservations began to slide mid-March. Guests started leaving, or canceling, their bookings when the lifts stopped spinning at Grand Targhee and Jackson Hole Mountain Resorts.

“When the resort closed, we took the steps to encourage people to kind of head on back home because we were distancing our employees and so without staff, you know, housekeeping, maintenance, we just wanted to make sure that units got empty and that people were respecting isolating,” said Kristie Eggebroten, manager of 25 properties at Targhee. “People were still coming here to party and have fun, you know, family reunions.”

One unit remained open for medical reasons, but that was vacated recently. All other reservations were canceled and refunded. The housekeeping staff was laid off; some resort workers stayed put in employee housing with nowhere else to go. “It was an abundance of caution, I think, for our employees and our guests,” Eggebroten said. “We just didn’t feel like it was worth the risk. But the financial impact is enormous. Now that Targhee is not leasing these units out, those owners aren’t receiving any revenue. And when they don’t receive that revenue and still have to pay their mortgage, that’s something they haven’t seen before.”

Owners were strongly discouraged from coming out and enjoying their homes, now vacant. “It’s just tough because our health system is so small,” Eggebroten said. “And, you know, if we were to get inundated with a lot of folks traveling in, we’d get the same issues that Sun Valley was having where they just couldn’t handle it.”

Vacation Rental Havens

Stacy Stamm lives in Teton Valley, Idaho, and has a studio apartment attached to her and her husband’s home. She opened up the property for the entire month of April in hopes of helping locals in need of housing. The familiar off-season exodus to the desert or further afield isn’t possible this year, leaving people with gaps in leases and plans. Two hours after Stamm posted her digs, two seasonal workers who’d been planning on an international trip filled it.

“They really needed somewhere to stay, essentially at Vietnam pricing, since that’s what they had saved up and were planning on spending,” Stamm said. “So it worked out really well. I just felt bad having an empty space knowing that people needed something.”

Suddenly-open vacation rentals are acting as a haven of sorts. Sam Reece owns and manages a combination of three properties, two in Wyoming and one in Idaho. His studio apartment in Victor is giving a summer employee a place to self-quarantine instead of moving into a home with multiple roommates during the pandemic. “We offered him a screaming deal for April because we were going to have it empty anyway,” Reece said. “We’re not promoting anybody coming into the valleys right now.”

His Teton Village condo is also providing refuge for stranded tourists. “They were here traveling in March and they decided not to travel or fly home,” Reece said. “They lived in the Motel 6 for three weeks.”

Urban Dwellers Escape

As skiers packed up their gear and headed home, other urbanites eyed the same mountains as a perceived escape from the virus. Nationwide, rural areas in northern and Midwest states reported significant year-over-year gains. According to a story in the Montana Free Press, vacation rental data from Air DNA showed Montana vacation rental revenues were up drastically as the outbreak spread in early March.

Whitefish saw a 92 percent revenue increase, Livingston was up 107 percent from the year prior. An Air DNA analysis of states’ short-term rental markets impacted by COVID-19 found that “northern, Midwest states are seemingly far less vulnerable than their southern and coastal counterparts” for several reasons. These states have fewer (and less populous) urban centers, and they boast quicker access to off-the-beaten-path destinations. The company described rental activity in March as a “boom” for these non-urban areas, including Wyoming.

While many other short-term rental markets have taken a hit amid the COVID-19 pandemic, revenues in Wyoming were strong in February and March. (Emily Cohen)

Zipcodes around Jackson Hole also paint a picture of increasing revenues for February, especially, and March despite, or perhaps partially because of, COVID-19. While numbers of active properties varied between the years, increases in revenue were across the board. Air DNA data for both Airbnb and VRBO properties showed a 90 percent increase in Jackson’s February revenue compared to the same time last year. That dropped to a 5 percent revenue increase in the month of March. Wilson saw a 35.5 percent revenue increase in February and just over 12 percent increase in March. Teton Village, a 70.5 percent increase in February and another 12 percent increase in March.

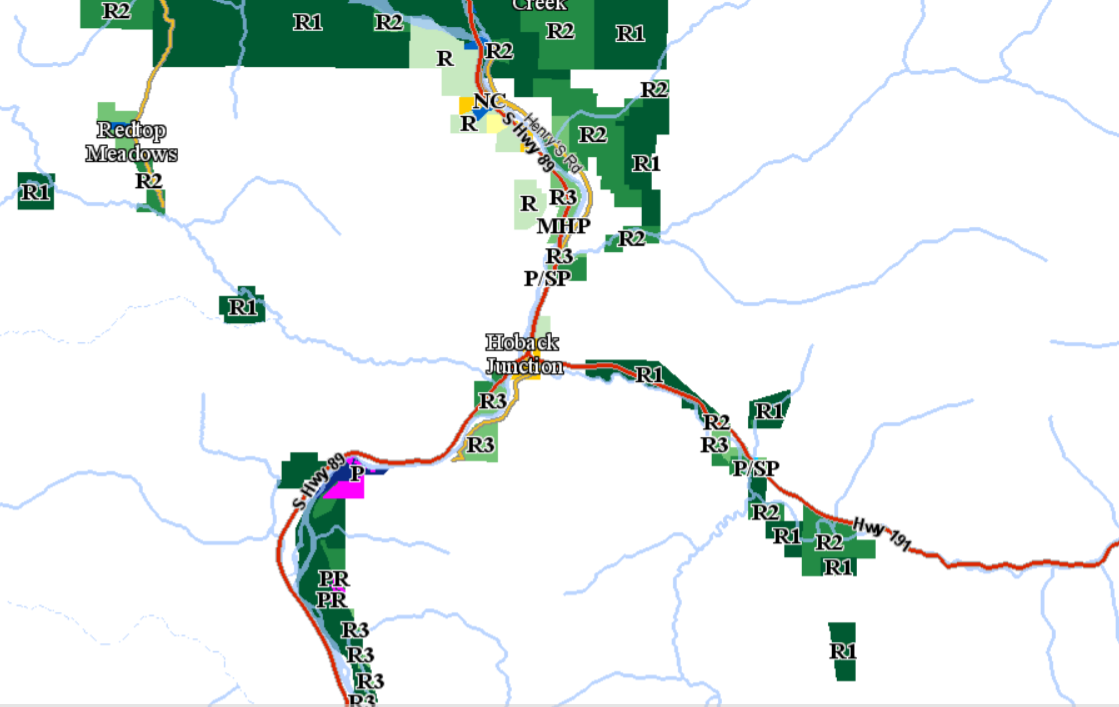

But some revenue from western Wyoming properties could be coming from illegal rentals. An Airbnb search for Jackson Hole shows available rentals that appear to violate Teton County land development regulations. The county prohibits short-term rentals in most areas including in the R1, R2 and R3 zones where many of the properties appear to be located. According to Section 6.1.4 of county LDRs, the minimum rental period for primary residences in those areas is 31 days. Guesthouses, or accessory residential units, have a minimum 90-day lease requirement.

- An April 27 map of available properties listed on Airbnb with their nightly rates. Many appear to be in zones that prohibit short-term rentals.

- For comparison, a map from the Teton County geographic information system shows the R1, R2 and R3 zones where short-term rentals are prohibited.

Eastern Idaho saw similar numbers. Victor’s short-term rental revenue was up 65 percent in February and 27.5 percent in March. Driggs increased 67 percent in February and 17.6 percent in March.

Some realtors, like Reece, are seeing rising interest not in short-term rentals, but in long-term properties. He says people now more than ever want to settle down in the Tetons. “How many people are sitting in their 600 square foot studio in Manhattan or L.A. right now, wishing that they were in Idaho or Wyoming, dreaming about social distancing in a natural setting and blah blah blah,” he said. “I’m currently still talking to people and putting stuff under contract sight unseen. People are sitting in front of their computer in Chicago or New York, and they just want out. They’ve been dreaming about a mountain house, and they’re just finally pulling the trigger on it.”

Meanwhile, many short-term rental hosts are clamping down on those who want to visit now. Stamm accidentally left a weekend open at the end of March and someone tried to book it. “I essentially said, nope,” Stamm said. “Because they wanted to come visit, their kids were out of school. They were like, ‘We’re just gonna come on vacation. And I was like, well, you can’t stay here.’”

Devin Dwyer works for an international travel company with properties in Teton Village and also runs two of her own properties in Idaho. She and her employer have gently tried to tell visitors that it’s not a good time to visit. “They wanted to check in on the 16th and they had a California contact number,” Dwyer said. “I denied their request to come.”

But then the market swung again, this time, with prohibitions banning that kind of behavior.

No Vacancy

Cities and counties around the Mountain West are taking their state’s stay-at-home orders a step further, explicitly calling out short-term vacation rentals and other spots frequented by visitors with varying levels of strictness. Teton Valley recently joined the ranks.

“We have essentially a global pandemic and a national pandemic, which is being addressed through a patchwork quilt of frequently conflicting local and state jurisdictions,” said Bob Heneage, commissioner for Teton County, Idaho. “It’s tough. We’re doing the best we can.”

The city of Victor, Idaho, passed on April 8 ordinances forbidding non-essential reservations in hotels and vacation rentals. Teton County, Idaho’s board of county commissioners expanded the directive, adopting a resolution on April 13 asking lodging facilities to stop renting to anyone except a few key groups—residents, healthcare workers and government employees performing essential government functions—until at least the end of May. A resolution lacks the legally binding teeth of an ordinance. But ordinances need enforcement support from a city or county attorney and the Teton Valley News reported the city has no plans to pass out misdemeanor citations for violations and instead hopes to promote public education.

Commissioner board chair Cindy Riegel told KHOL that while she wanted an ordinance for the county, the resolution was a compromise she was hopeful people would abide by. “The reason I felt OK about doing a resolution is because, for the most part, they’ve been followed,” Riegel said. “So it’s working when we’re asking people rather than telling them to do something and giving them a penalty.”

Heneage said he received a request to avoid Memorial Day in any ban on rentals. He hopes mud season will deter folks from coming at all. “If we have to deal with a pandemic, it’s a lot better to deal with it during a shoulder season than in another time of year,” Heneage said.

Teton County, Wyoming, has no restrictions on reservations. Teton District health officer Travis Riddell said his job is to do what’s best for public health without making it so complicated that nobody knows what’s going on. Riddell says asking people not to visit via an official recommendation he issued recently is enough for now.

“Having some flexibility without legal binding makes it a little easier for people who can interpret those rules for themselves and decide if their own activity is essential or nonessential, rather than us trying to codify that,” Riddell said. There is a statewide travel directive, however, that says people listing hotels, rental properties and short-term rentals in Wyoming must notify travelers of the mandatory 14-day quarantine in their listing and at the property. It doesn’t look like many, if any, properties on Airbnb have that information on their main page accessible prior to trying to reserve a date. And while the company has a travel restrictions and information page, the state of Wyoming isn’t listed at all and Idaho information only pertains to Ketchum.

Moab, Utah, led the charge back on March 17 with an ordinance limiting hotels, properties and campgrounds to residents as fears of crowds overburdening small medical facilities spiked. Now, anyone entering the state of Utah must submit a travel declaration.

“I think there’s just a lot of fear involved. People are wanting to reduce the influx into the little towns, which makes a lot of sense. But they don’t have to hate people over it.”

In Montana, Whitefish became the first city in that state to ban nonessential lodging on April 5. Days later, Montana’s Madison County, a renowned fly fishing destination, shut down hotels and vacation rentals except for essential purposes. Property owners and managers said that potential clients have been overwhelmingly understanding.

Paul Diegel, 60, lives in Salt Lake City and owns a property in Driggs. He said he didn’t need anyone to force him not to come. “Certainly it’s frustrating,” Diegel said. “I would love to be up there. And if I’m not there, I would love to be generating some income out of it. But it kind of is what it is. Fortunately, I’m not depending on that income. And the community has been trying hard to not encourage people, second homeowners to come into town. Typical small resort town, they don’t have the hospital facilities. It’s just not a good place to have a sudden influx of visitors and as much as that bums me out, I have to respect that.”

Communities on both sides of the Tetons are still giving the side-eye to people they think might be visiting from out of town. “I think [there’s] just a lot of fear involved,” Eggebroten said. “And, you know, people are wanting to reduce the influx into the little towns, which makes a lot of sense. But they don’t have to hate people over it.”

In 2016 Adam Lackner bought a tiny home trailer to rent out. Guests are usually drawn to a “farm stay” experience with his family’s chickens and horses in addition to Teton Valley’s proximity to Grand Teton National Park. Income he generates from it helps send his kids to college. A German woman booked the property 20 days ago, has been staying there for at least 10 and will be staying at least another two weeks. “We think we have somebody that booked sheltering in place in it,” he said. “We don’t really mind that.”

Facebook debates are breaking out over neighbors potentially continuing to rent properties. Lackner is feeling the judgment. “I think my neighbors aren’t too happy that somebody is in our Airbnb … But it is what it is,” he said. “We feel we can manage it, and it’s nobody’s business but ours. We pay our taxes on our private property is the way I feel about it.”

He manages two other rentals—a long-term spot above his garage where he’s cut rent because times are tight—and a property across the street. There were so many rental cancellations there, the cabin’s owner’s moved back in temporarily. Airbnb is now distributing $250 million to help hosts seeing scores of COVID-19 related cancellations between mid-March and the end of May. Guests can get a full refund, hosts will get 25% of what they would’ve pocketed.

Summer Uncertainty

As a co-owner of Brushbuck Wildlife Tours, Lackner is feeling the pinch in more ways than one. “We’re heavily invested in the tourism market, with our fleet of vehicles and wildlife tours,” he said. “We’re gonna get pummeled, I can feel based on all the cancellations coming in.” Realtor Karin Wertheim owns three short-term rentals and manages another seven in Driggs. She’s already seeing people change their summer lodging plans and is issuing 100 percent refunds because it’s the “right thing to do.”

“None of the vacation rentals have occupancy through May,” Wertheim said of her properties. “Most of the June rentals have canceled as well. I believe I processed two July cancellations on Saturday. So we’re seeing lots and lots of cancellations. Business is pretty much dead.”

“It’s given me perspective on the climate of what the rest of the country is feeling. I think people in California and New York are experiencing this on a whole other level.”

Dwyer is seeing similar summer cancellations on her properties. She thinks that’s likely indicative of the virus’s intense impact in bigger cities around the country. “It’s given me perspective on the climate of what the rest of the country is feeling,” Dwyer said. “I think people in California and New York are experiencing this on a whole other level.”

It’s unclear when national parks will reopen. But people are optimistic that more local and regional travel could pick up later in the summer, that is, if travelers haven’t already postponed their trips due to lost wages or financial uncertainty.

“I just think people are going to be itching to go do something,” Reece said. “So it’s going to be maybe a very different clientele than our normal summer, but I think that people are going to be ready to get out and do stuff once we have the ability to.”

Robyn Vincent contributed reporting.