Say this: “I believe you. It’s not your fault. I’m here to listen.”

That’s the advice Community Safety Network education and prevention director Adrian Croke gave to a packed Zoom room Tuesday. Faces peered out from home offices and living rooms, earnestly taking in Croke’s guidance. The group of roughly 40 participants included community members, local elected officials and candidates. The fact that many people attended from home lent an intimacy to the intimate topic at hand.

Conversations centered on sexual assault reached a tipping point this month as Mayor Pete Muldoon defended himself against a two-year-old allegation. This news reverberated through the community, with many people wondering what can be done about sexual assault in general. The issue had been bubbling up through the summer with Act Now JH members testifying about how law enforcement mishandles sexual assault. A police blotter post making light of a potential sexual assault incident deepened the tension. The post’s author, former Jackson Police Lieutenant Roger Schultz, ultimately resigned.

Victim advocates say sexual assault is rampant in Teton County. Changing the culture that perpetuates it may hinge on listening to, and believing, survivors.

Supporting Survivors 101

Croke started Tuesday’s basic training session by defining terms. She talked about Intimate Partner Violence, which includes some kinds of sexual assault. According to the Centers for Disease Control, IPV is a public health problem affecting millions of Americans.

Sexual assault occurs not only at the hands of intimate partners, but also by people known or unknown to the victim. Often people think of rape when they hear sexual assault, but rape is usually confined to a legal definition of assault that includes some kind of penetration. Sexual assault is broader and includes any kind of unwanted or non-consensual sexual touch.

The scope of the problem is vast.

According to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network, someone is sexually assaulted in America every 73 seconds. Nearly every minute of every day, a sexual assault is taking place. Viewed through a lifetime lens, the statistics are dire. According to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC), 1 in 6 women and 1 in 33 men in the United States will experience an attempted or completed rape at some time in their lives.

What this looks like in real time at the state and local levels is unsettling. According to the Wyoming Division of Criminal Investigation, in 2019 there were 275 forcible rape offenses, including attempted rape, in the state. But because the state defines forcible rape as some form of penetration, other kinds of sexual assault are not reflected in that number.

Teton County Sheriff’s Office received 36 calls for service for sexual assault in 2019. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, only 230 out of every 1,000 sexual assaults in the U.S. are reported to police. That means about three out of four go unreported, which suggests roughly 145 sexual assaults took place in Teton County in 2019.

False rape allegations are somewhere between 2 and 8 percent depending on the study, Croke said. “When a survivor confides in another person, it is far more likely that they are telling the truth than not. Saying ‘I believe you’ is the first step in building the necessary trust to support that survivor.”

With sobering statistics as a starting point, Croke told the training attendees the good news. They can make a difference.

“When a survivor first comes to someone and tells their story, especially if it’s the first person they tell, that person has an immense opportunity to create a positive influence on that survivor’s trajectory of healing,” she said.

Croke said saying the right things is crucial:

“I believe you.”

“Thank you for telling me, that was very brave of you.“

“I’m so sorry this happened to you.”

“You don’t deserve to be treated this way.”

“This is not okay.”

“It’s not your fault.”

“I’m here to listen.”

When participants were sent to small group breakout rooms to practice these words, it was harder than some expected. One person in each group was the survivor coming forth with their tale. “I think I was assaulted,” a role-play victim would say.

For Teton County Commissioner Chair Natalia Macker, those words were “startling to hear,” she said.

Croke told participants that it was natural to want to find a solution. But that’s the opposite of what’s needed when someone confides in you.

The key is empathy, Croke said. “You are sitting with them in their pain. You are bearing witness to their trauma.”

Macker was struck by the courage it takes not only for a survivor to come forward with their story but also the courage required of a listener. “Giving support is simple, but it also requires a tremendous amount of bravery,” she said. “You have to be willing to take the plunge and get in there with them.”

Changing the Narrative

Prior to the training, Croke expressed frustration with the conversation she’d seen on social media by some candidates. “I want there to be political conversation about sexual assault and I want there to be politicians who care. But the way it’s happening right now does not feel at all sincere, positive, or healthy.”

Croke sees ways in which survivor stories have been weaponized for political arguments on social media. She wants elected officials to care about sexual assault not just to win votes, but because it’s the right thing to do. She worries that the heightened community conversation about sexual assault may be fleeting. “Is this our only moment to have a political conversation around this in a way that makes any sort of policy change?” she said.

Though Croke had planned to offer a training anyway this fall, she seized the moment now in light of community discussion. She wanted to steer the conversation toward what people can do to support survivors, “rather than put the onus on survivors to tell their stories or educate the rest of us.”

Speaking out publicly can be empowering for survivors. But it comes with costs too.

Eden Morris spoke out October 5 at a Jackson Town Council meeting. She told the story of how Mayor Muldoon sought her out privately on Facebook and asked her to remove a post in which she referenced fleeing an attempted rape in college. The post had been the first time she had spoken publicly about the attempted assault. Though her post had been inspired by her friend Jessica Gill, who had posted her own sexual assault story as a way of standing in solidarity with the person who accused Muldoon of assault, Morris maintains that she did not know Muldoon or anything about the allegations against him.

During her testimony, she also told the story she had told in her post. She spoke of having been sexually harassed by a professor in graduate school.

Morris said she experienced a range of emotions after speaking out.

“I absolutely knew that doing what I did would take a huge hit on my health,” she said. She experienced sleep disturbance, stress, and appetite issues before and after her public testimony.

“As empowered as I felt after I addressed the town council, I also felt so much fear re-emerge.”

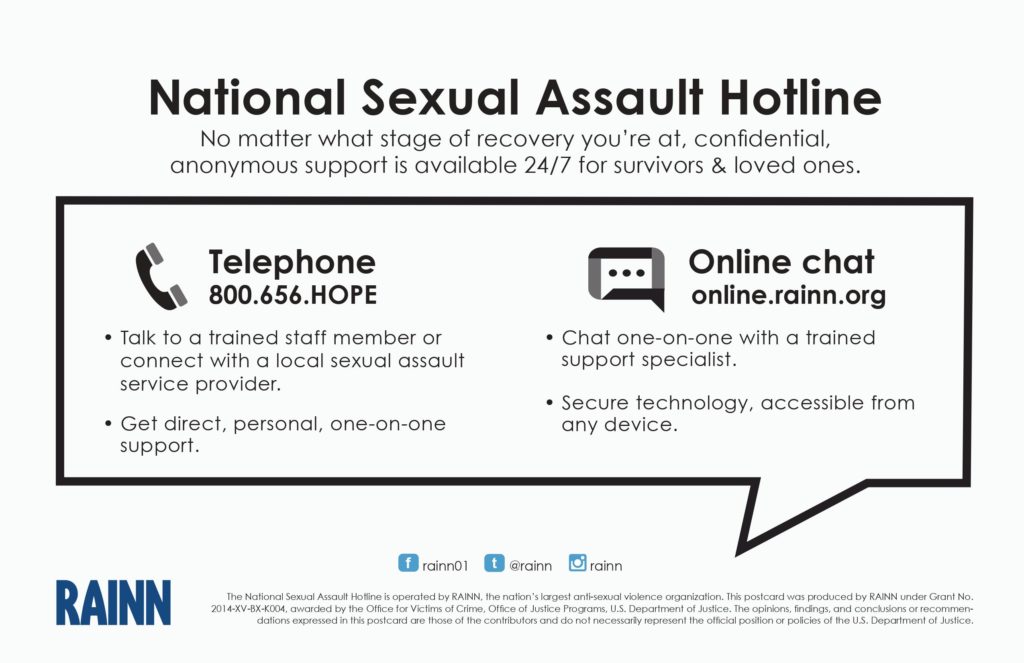

One of her strategies was to call the CSN helpline, an option she recommends to any survivor anytime.

Not all survivors want to jump into the public fray, Croke noted. And that’s just fine, she said. Survivors get to navigate their healing journey in their own way. But speaking out does help change culture—as long as people are listening, and willing to take collective action. One action is to adequately fund social services that support victims, said Teton County Commissioner Luther Propst.

“Our entire society needs to prioritize human services,” he said.

This means two things, Propst said. Philanthropy needs to step up and not just fund flashy projects, but also support the steady behind-the-scenes work that keeps the community nurtured and whole.

Propst also wants for voters to pass the general penny on the general election ballot. He says it would enable the county to fund human services even in the face of what Gov. Mark Gordon has described as “devastating” state cuts. For example,

Jackson Hole Community Counseling Center executive director Deidre Ashley said she is anticipating up to $150,000 in state cuts to her budget.

Disrupting Cultural Norms

While better support for sexual survivors is needed, prevention is also key. Many prevention efforts focus on coaching people on how not to get in a dangerous situation. But that approach has a pitfall – it puts the responsibility on the potential victim. In order to stop people that commit assault, society needs to change. According to a scientific review of intervention strategies, unless the cultural landscape becomes intolerant to sexual assault, “It is unreasonable to expect that people will change their behavior.”

According to NSVRC, addressing the big picture of gendered power relations and a culture that glorifies sexual violence has to be part of the change.

Morris says structural change comes down to ethics rather than relying on laws that may not serve survivors.

“It is almost impossible to prove that a crime occurred in a situation where a possible sexually inappropriate act occurred,” Morris said.

Morris wants society’s values to mirror the oaths public officials make when sworn into office – or even marriage vows. If people held true to honoring and caring for one another, communities would benefit. She said the question remains, “How do we put these values into legislation?”

Macker has the same question. It’s impossible to legislate empathy, she said, But empathy can lead to changes in public policy.

This was a strategy that worked for LGBTQ advocates. By focusing on changing hearts and minds, they were able to achieve marriage equality rights for all. The effort took years, but it resulted in laws that allow and protect same-sex marriages.

Wyoming Rep. Mike Yin said the state legislature is at square one. “The best place to start is taking a look at sexual assault statutes,” he said. “They haven’t been good for a while. It was something that got put on the bottom of the priority list this past year.” He says he will try to make them a priority in the next legislative session.

Changes to statutes will likely be slow in coming. But survivors can still share their stories, showing just how many people have been affected by sexual violence. Morris says she is proud she faced her fears and added her voice to the survivors’ chorus. “Moving forward despite crippling fear is how we inspire ourselves and realize how strong we actually are.”

CSN will offer another Supporting Survivors 101 webinar training on October 27. Contact Adrian Croke for more information, 307-733-3711. The CSN Helpline is 307-733-7233.

*****

Reflective Writing for Supporters of Sexual Assault Survivors

Poet and writing instructor Matt Daly (this author’s brother) designed a course for the Harvard Medical School Continuing Education program entitled, “Reflection and Resilience: Principles and Practice for Clinicians.”

Daly offered a practice exercise drawn from his work with doctors.

Write two letters that you will not send.

The first letter is from you to the survivor. Think about an experience you’ve had together or an activity that’s healing and nurturing. Think of your relationship in its best light. Write a letter to the trauma survivor acknowledging their story and putting it in the context of your positive relationship. Express your feelings about hearing their story.

Write a second letter from the survivor’s point of view. Imagine that you have given them your letter and now they are writing back to you. Try to use their voice and imagine what they would say. “Empathy isn’t putting yourself in someone else’s shoes,” Daly said. “Empathy is an imaginative act. You are imagining them as themselves, not as you.”

Daly then suggests taking elements from each letter to write a poem. The idea is to let empathy lead the writer to a creative response to trauma. Even if writers choose not to share their poems, it can be a way of processing the hard work of supporting others.

“Reflective writing slows down our observational process so that we might actually notice and observe our internal-external world,” Daly said. “You can’t write as fast as you can think. Writing allows for awareness of your thoughts.”