Walk around the waterways in Grand Teton National Park, and it’s not hard to see how the climate is changing Jackson Hole right before our eyes. Upstream of Jackson Lake, Pilgrim Creek is reduced to a slow trickle amidst a plane of dried-up stream beds due to low rain and snowfall.

Pilgrim Creek in Grand Teton National Park. (Will Walkey/KHOL)

Downstream is Jackson Lake Dam, which is now releasing four to six inches of water a day into the Snake River to help Eastern Idaho farmers. Look up toward the Tetons, and you’ll likely see just faint outlines of ridgelines and a bright red sun through a thick haze caused by Western wildfires.

The Jackson Lake Dam. (Will Walkey/KHOL)

This all sounds familiar to Charles Drimal, who lives in Bozeman.

“Oh man, it’s been a rough summer here,” he said.

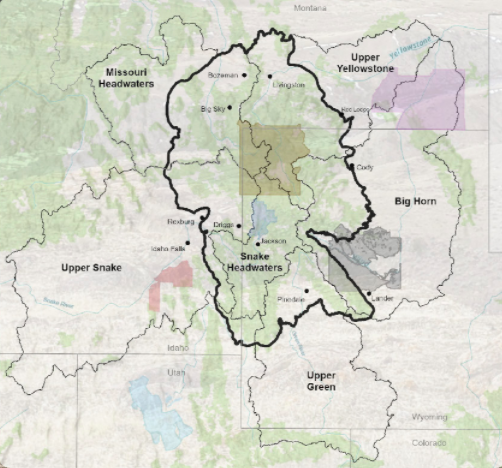

Drimal is the water conservation coordinator for the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting one of the largest intact ecosystems in North America: 22 million acres spanning three states, two national parks and thousands of people from Pinedale to Driggs to Livingston, Montana.

“The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is an extraordinary natural and cultural landscape. There’s no other place like it in the world,” Drimal said.

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. (Screenshot courtesy of the Greater Yellowstone Climate Assessment)

That’s why Drimal, like so many others across the region, has been seriously affected by climate change over the last few years. It’s one thing to read about global trends of more frequent extreme weather events in a newspaper from the East Coast, but another altogether to watch that playing out in your backyard.

“To hone in on your homeland, to hone in on this specific region and actually see very specific changes that have happened from 1950 to 2018 is very sobering,” Drimal said.

Over the past three years, scientists and statisticians from several academic institutions like the University of Wyoming poured over historical data to look at how much the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem has changed since the mid-20th century and how much it could change in the coming decades. Their work culminated in the mammoth, eight-chapter, Greater Yellowstone Climate Assessment, released in late June.

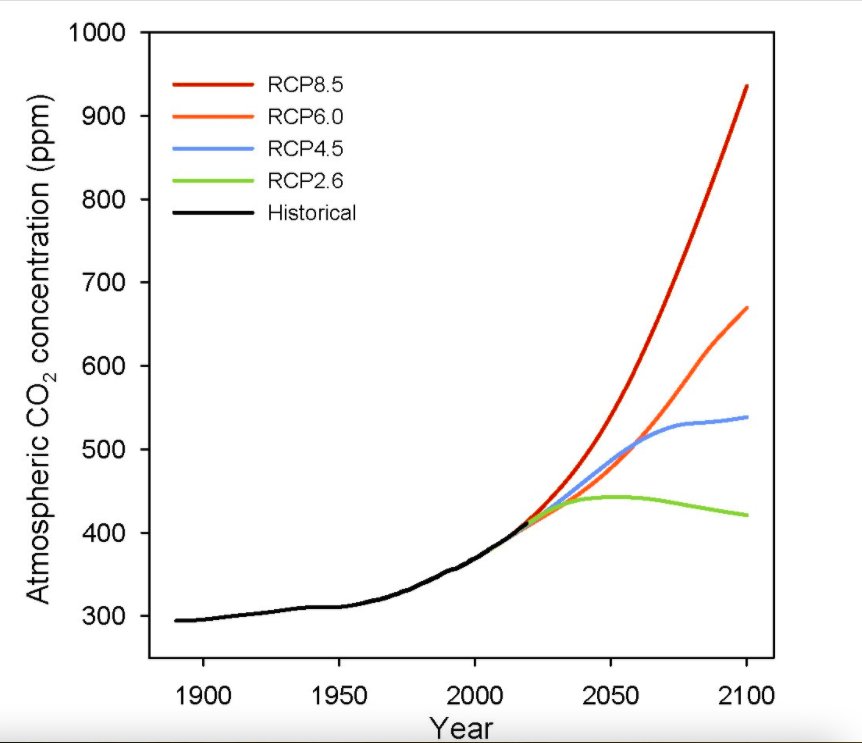

“The report summarizes how climate change could progress by 2100 based on various greenhouse gas concentration scenarios and [it] concluded that since 1950, temperatures significantly increased, snowfall decreased, and snowmelt and stream runoff is occurring earlier in the spring, adding to water shortages in the summer because of climate change. And the trends are likely to continue,” Drimal said.

The average temperature in the ecosystem has gone up by 2.3 degrees and is projected to continue warming. That means wildfires that burn longer and hotter, massive shifts for local wildlife and fish, and many other disruptions.

“I love winter. I love snow. And I love them for their aesthetic, for their recreational opportunities. Also for our rivers and for our industries, for outdoor recreation, for agriculture, and to see basically our essential water storage decreasing by 23% in that roughly 70-year period is very alarming,” Drimal said.

Another author of the report, Steve Hostetler, is a climate scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey, based in Corvallis, Oregon. He said research indicates that the changing climate will alter life in our region no matter what. But there’s tons of variability depending on how we humans interact with our planet over the coming decades.

“Given how long this persists, carbon dioxide persists for a long, long time,” Hostetler said. “Even if we stop today, the effects of this are going to be felt for a long time because the oceans are still absorbing heat, glaciers are still melting and it takes a long time for everything to kind of come into balance. But on a lower trajectory, we can certainly do a lot in terms of making a big difference for the whole planet.”

Various potential climate scenarios over the next century modeled depending on greenhouse gas emissions from humans, which could subsequently affect average temperatures, water levels, precipitation and more in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. (Screenshot of the Greater Yellowstone Climate Assessment)

Hostetler helped create a number of possible future scenarios for the report. In one, humans start to reduce emissions now, and temperatures level off by around 2050.

“The other one is the upper bound scenario,” Hostetler said. “It’s kind of been known as business as usual.”

The difference between the two scenarios is staggering. With reduced emissions, temperatures across the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem increase by an average of five degrees by the 2060s. In the business as usual model, the increase doubles to 10 degrees by the end of the century.

“If you move the baseline up, let’s just use temperature, by two or three degrees, now you’re in a new world where you’re working for different baseline conditions. That presents a bigger management problem because we have that going on. We have changes in the seasonality of water availability and so forth,” Hostetler said.

Both Hostetler and Drimal said they’ve seen great responses from a slew of concerned citizens since the release of their report. Part of Drimal’s job when producing the report was to interview leaders in the region, from tribal heads to water managers about their feelings on climate change. He hopes having some hard data in the hands of the public will spring people into action.

“I think that there is also a desire to see more direction coming from the top of their agencies, whether they’re in Helena, Cheyenne, or Boise or from Washington, D.C. to provide more resources to really address this,” Drimal said.

Drimal also said, for so many folks in the region, entire livelihoods are at stake. Ranchers can no longer rely on reservoirs. Outdoor enthusiasts, hunters and anglers can’t do what they love as much, and businesses might not have steady revenue from tourists in the coming decades.

“By addressing water issues like availability and quality and future climate adaptation work, we stand to have positive impacts on myriad other conditions, including wildlife, habitat, fisheries, health and the economy of local communities,” Drimal said.

Drimal and Hostetler will help host public meetings this fall throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, including in Jackson, to discuss the report. The pair said they expect a lot of interest from locals in Jackson and elsewhere who love the places they live and whom they believe will want to help preserve it as much as possible.

Sheep Mountain, aka “Sleeping Indian,” as viewed from the National Elk Refuge in July 2021. (Will Walkey/KHOL)