About 100 bighorn sheep call the Tetons home, often living on windswept ridges between elevations of 8,000 to 12,000 feet. Backcountry ski guide Zahan Billimoria has been recreating in the Tetons for more than two decades, and he said he’s only encountered the species a few times.

“That’s like a sacred animal,” he said. “And if you see it, for one, you’re in awe of it because it is so rare. And for two, you recognize because it’s so hard for us to survive up there and to avoid avalanches—to not fall off the side of the mountain—and all the effort that it takes to get there. So, I think that there is this amazing admiration that we all have for these creatures.”

Bighorn sheep historically inhabited the entirety of Jackson Hole and once numbered in the thousands. But loss of habitat due to human development and invasive species has rapidly diminished the herd’s numbers over the past few decades. Now, the sheep are in danger of local extinction, should their situation get worse, according to many biologists who live in Teton County, including Aly Courtemanch of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department.

“The herd is small. It’s in trouble,” Courtemanch said in a public Zoom meeting in October. “But it’s not doomed at this point and we can change things, but we have to act quickly.”

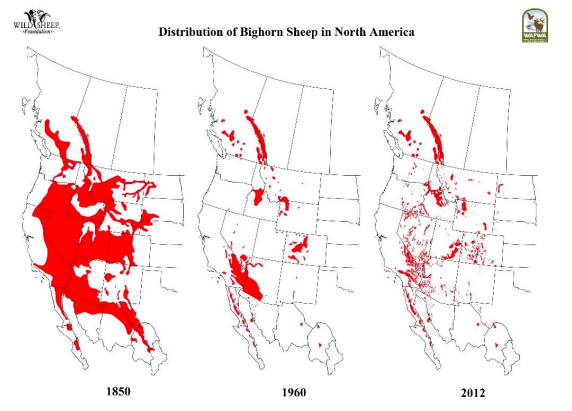

The historic range of bighorn sheep has declined dramatically across the Mountain West over the last century. The Teton herd has now been cut off from the rest of the range, making them genetically isolated. (Screenshot courtesy of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

Courtemanch is helping lead the charge among local biologists to try and double the local bighorn herd’s population to 200. Some tactics that have been used to try and reach that goal have included killing off invasive mountain goats and educating the public about the plight of the sheep. But the most controversial measure is easily proving to be newly-proposed winter closures that will impact backcountry recreation.

On Oct. 20, more than 250 people gathered over Zoom to discuss potential closures in and around Grand Teton National Park. Several wildlife and public lands experts weighed in on how we’ve gotten to this point.

“Very little of our sheep winter habitat is currently protected from human disturbance. Our proposals would increase this by tenfold,” said wildlife biologist for Grand Teton National Park Carson Butler.

“Given our rapidly growing human communities, we need to find the restraint needed to give the sheep some space,” said Michael Whitfield, who’s been conducting field research on the bighorn herd since the 1970s.

At least one peer-reviewed study, conducted by Courtemanch, has found the presence of backcountry skiers negatively impacts the Teton sheep herd, while others have documented similar negative impacts from human recreation on bighorn sheep elsewhere. That’s because the animals tend to avoid otherwise prime habitat at all costs even if they cross paths with only a few humans there, and local experts almost unanimously agree with that current scientific research. So, the Teton Range Bighorn Sheep Working Group is recommending closures in several iconic ski mountaineering destinations, including parts of Cody Peak, the South Teton and Avalanche Canyon, in order to reduce the number of interactions between sheep and skiers.

“If all of the recommended closures in the document were put into place, a total of 47% of the mapped bighorn sheep habitat would be protected under closures,” Courtemanch said during the recent meeting. “And then, again, if all of the recommended closures were put into place, 5% of the areas that were identified as highly valued by the ski community during the collaborative process would be closed to human entry from December through April.”

One of the recommended closures in Avalanche Canyon, featuring an approved “passage” that would allow for backcountry traffic. (Screenshot Courtesy of the Teton Range Bighorn Sheep Working Group)

Several public workshops were held last winter to explore which closures might be acceptable for skiers and which ones were deal-breakers. But during the Oct. 20 meeting, it was clear that many folks are still unhappy with the current proposals.

“Many of the messages I’ve received reflect disbelief by individuals from both communities about the unwillingness of the other side to compromise,” said local mountain guide Jeff Dobronyi, who has become one of the vocal opponents of the proposed closures.

“I just don’t feel the data you have justifies something this important as closing wilderness to humans,” said Nick Mestre of Driggs, Idaho. “I mean, that’s a tough one to swallow.”

Billimoria also said he thinks the current proposals go too far.

“When we come to a place where humans become banned in perpetuity from being able to explore and travel in these remote corners of the range, then we really do lose something as a community that is more, I think—is a greater price than the benefit is.”

View this post on Instagram

Billimoria also said he feels like the backcountry ski community is bearing too much of the burden to save the sheep. For example, he brings up the point that much of the historic sheep habitat falls within the Jackson Hole and Grand Targhee ski resorts, but none of the proposed winter closures are located there. Several sheep hunting tags are also still sold every year for male sheep that cross out of the park.

“The reason that we’ve got here is, in reality, because Jackson has really fallen off the cliff, in my opinion, as far as its ability to balance visitors and growth with a true wildlife and wilderness ethic,” Billimoria said.

Jed Porter is another longtime backcountry guide who’s approaching the issue from a different viewpoint. He said he wants to see the skiing community take the matter into their own hands and voluntarily avoid areas identified as high-value bighorn habitat, a position he outlined in an op-ed for the website WildSnow.

View this post on Instagram

He also said many of the proposed closures fall in some of the most remote areas he’s ever skied.

“There’s only a very tiny subset of the entire backcountry ski community that can make it that far to get to these proposed closure sites,” Porter said. “So, why bog down the bureaucratic system with closures when a handful of social media influencers could spread the word? And we’d just avoid the spots and let the sheep be for a bit.”

Additionally, Porter said the backcountry areas in question have really only been accessible to humans for a few decades thanks to technology and gear advancements. But during that time, he said, it’s the sheep who have sacrificed as a result.

Porter is also frustrated by the widespread outcry he’s seen from his friends and fellow guides, whom he would like to see give more respect to the local biologists.

“I guess I’d like to see some acceptance of the science, first of all,” Porter said. “You know, the science is rough. The science is inconclusive, but that’s sort of the essence of crisis-based science. Any environmental crisis is going to be uncertain.”

While it’s a complex issue, most guides who have gotten into the fray on social media appear to really want one thing: Communication. They want to know how the closures will be monitored for success if they should go through, and when—if ever—those wilderness areas might be open to exploration again.

As of press time, wildlife managers have said they’ll continue to work with the backcountry community over the coming months to hone in on exact closures. But at the same time, many conservationists are hoping for swift action before the bighorn habitat diminishes any further.

More information about the proposed closures and how to get involved in the collaborative process is available at tetonsheep.org.

Biologists have been warning over the past few years that even small numbers of backcountry travelers (and their tracks) can disturb sheep. (Kevin Cass/Shutterstock)