From a young age, Courtney Roberts was an outsider in her hometown. Roberts is biracial and growing up in Jackson she was one of few darker-skinned students in her class. That made for some fraught moments. Learning about Black History Month with a group of white peers, for one thing, distanced her further from classmates. She was not part of their experience. She was someone they learned about in their history book.

Recently she found herself reliving some of that discomfort when her seven-year-old daughter came home from school upset. She had just learned about civil rights activist Ruby Bridges. At six years old, Bridges took on a historic feat becoming the first African American student to integrate a Southern classroom.

For Roberts’ daughter, learning about Bridges was a window into a difficult life ahead: “She basically came home and said she didn’t want to be brown.”

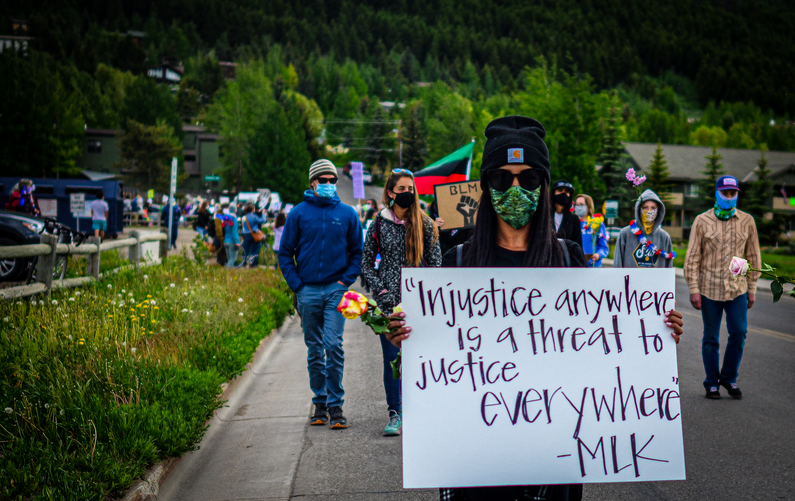

Roberts was among the hundreds of people that marched from the Teton County Fairgrounds to the Town Square on Sunday. She held a sign bearing the words of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” As she sat on the floor with her daughter making that sign days before, she explained to her, “We are facing some of the same injustices now that Ruby Bridges did then.”

Roberts said life in Wyoming has been a struggle and a balancing act. She has fought both for acceptance and against erasure. Raising her daughter in Jackson, she continues to face that struggle, but, she says, things are starting to feel a little different. “It chokes me up thinking about it—to hear people chanting ‘Black Lives Matter’ in the square,” she said, her voice quivering. “People are out here doing the right thing.”

It was the third local demonstration sparked by the death of George Floyd, an unarmed black man who died in police custody after a white Minneapolis police officer kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes. Floyd’s killing has triggered a national conversation about some of this country’s long-simmering ills: systemic racism and police brutality.

In Jackson, where the voices of people of color often go unheard, Floyd’s death has precipitated a reckoning. Protesters—many young and dozens from the Latinx community—poured into Town Square on Sunday for a rare moment. They sat down and listened while organizers led a public forum on racism.

“What does Black Lives Matter mean?” asked co-organizer Jailyn Wallace, an African American resident.

Jailyn Wallace, of the newly formed group Teton People of Color and Allies, encouraged protesters to listen to one another. He said white people should seek out black friends and vice versa to understand each others’ varied experiences. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

“It means that if black lives are not treated with the same value as ours, meaning the white people, then we have to do something,” audience member Ourdia Hodge said to a cheering crowd. “When people say, ‘All lives matter,’ I say, ‘Damn right all lives matter,’ that’s why when some lives are disregarded and treated less than others than we have to stand up and do something about it.”

Young protesters flanked by the American and Afro-American flags listened Sunday at George Washington Memorial Park at Town Square during a community discussion on racism. They were among hundreds to participate in a silent march and sit for the subsequent dialogue. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

A few members of the black community then obliged a young white woman and spoke about experiencing racism in Jackson.

“I’ve lived in Jackson for four years. I’ve been pulled over six times and three of those times I’ve been pulled out of the vehicle,” said Arthur Ellis, an African American resident. Since he was a child Ellis has been scared of the police, he said, and a clean record is the one thing that has safeguarded him from serious run-ins with the cops. “I just think about, what if I did have a prior, what if they did look at me a certain way?”

Issiah Smith Owens told protesters he did not experience racism, or the discomfort of being a minority, until eight months ago when he moved from Mobile, Alabama, to Jackson. He later described to KHOL a night at a Jackson restaurant when he fielded stares from patrons and overheard a server say to another table, “Don’t worry—they’re leaving soon.”

Wallace encouraged people with “different opinions” to speak, too, and one did.

Rebecca Bextel, among the counter protesters at Town Hall, made her way to Town Square and tested the crowd’s patience with a circuitous story about growing up in Jackson, Alabama. She asserted that poor white kids and poor black kids there faced the same problems and offered racist stereotypes akin to the welfare queen trope—that young black women see having babies as the only solution to climb out of a life of poverty. The crowd listened, interjected to challenge Bextel and eventually grew impatient. Her solution: “Stay in school and be married before you have children” was met with groans.

Mary Muromcew, 16, was among the folks who had heard enough. She wanted substantive discussion. And she wanted outrage. “I’m glad we’re having a peaceful protest, but if you’re not angry, then wake the fuck up!” she said. “We need to understand that racism is institutionalized.”

She pointed to black and brown people’s limited access to affordable healthcare and good education. The incarceration rates of people of color are also staggering, Muromcew said.

In 2017, African Americans represented 12 percent of the U.S. adult population but 33 percent of the sentenced prison population, according to the Pew Research Center. Latinx people were 16 percent of the adult population, yet they comprised 23 percent of incarcerated people. Meanwhile, white people accounted for 64 percent of adults but 30 percent of prisoners.

Muromcew, who is Asian, urged white people and nonblack people of color to challenge their “anti-blackness,” or the “inability to recognize black humanity,” as examined by Dr. Kihana Miraya Ross in The New York Times.

Anti-blackness, Ross writes, “captures the reality that the kind of violence that saturates black life is not based on any specific thing a black person—better described as ‘a person who has been racialized black’—did. The violence we experience isn’t tied to any particular transgression. It’s gratuitous and unrelenting.”

Talking it Out

To be sure, this type of dialogue is seldom heard in a Jackson public forum with hundreds of attendees to boot. Wallace said sparking such conversations was central to the protest. He is co-president, along with black resident Koriann Arritt, of the nascent group that organized the march, Teton People of Color and Allies. The group’s genesis can be traced to a May 31 Black Lives Matter rally that Luke Zender, who is white, organized.

Co-organizer Luke Zender is among the founding members of the new group Teton People of Color and Allies. He held a sign on Sunday to show his support for the lives of black trans people who are disproportionately affected by violence. Two black trans women, Riah Milton and Dominique “Rem’Mie” Fells, were killed last week. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

Wallace and Arritt told Zender they hadn’t heard about the protest until only moments before they arrived. Zender, disappointed he had not reached members of the black community, invited them to his house to discuss how he could center their voices. Other people of color and allies joined and the group was conceived.

In less than two weeks and with little sleep, Wallace said they made Sunday’s demonstration come to life. They coordinated with Jackson police, which provided a police motorcycle escort and officers to direct traffic on side streets during the march, scheduled speakers, purchased food and water, and marketed the event.

They faced some friction, however, when one member of the black community alleged the event was “politically motivated.” Rumors swirled that conservative billionaire Foster Friess, the former Wyoming gubernatorial candidate backed by President Donald Trump, had bankrolled the group.

The hearsay stemmed from a recent event. Wallace said he and Arritt attended Friess’ June 6 “Jackson Harmony Day Dinner” at Nora’s Fish Creek Inn. Friess has been funding these events all over the country and the dinner at Nora’s aimed to “lift up our police officers and celebrate the harmony in our community,” according to Friess’ website.

Wallace and Arritt agreed to attend the dinner to discuss issues facing the black community. But, Wallace said, nothing came of the event and they have not taken any money from Friess. “This is a pure grassroots campaign,” he told KHOL.

Further fueling the doubt of some, organizers set ground rules for the march. They said no chanting, encouraged people to carry American flags and family-friendly signs. A few on social media pointed out that the American flag has long symbolized oppression for black and brown people.

For Wallace, it is a sign of unity. “We are all Americans and want the American Democratic system to work for all of us,” he said.

That American Democratic system was built on the backs of black people, writes African American journalist Nikole Hannah Jones. In her essay for the landmark 1619 Project, reframing the founding of America to the year the first African slaves were forcibly brought to this country, she discusses her father’s pride for the American flag. For a long time, this evaded her. But Jones comes to understand that from the Revolutionary War to the civil rights movement, black Americans have played a pivotal role in building and shielding this country’s democracy.

“My father, one of those many black Americans who answered the call, knew what it would take me years to understand: that the year 1619 is as important to the American story as 1776,” Jones writes. “That black Americans, as much as those men cast in alabaster in the nation’s capital, are this nation’s true ‘founding fathers.’ And that no people has a greater claim to that flag than us.”

De-escalation and Escalation

As part of their “de-escalation” efforts, Wallace and his team handed out flowers to critics, like the dozen or so white counter-protesters stationed in front of Town Hall. The interactions were cordial. Counter-protesters smiled as Wallace handed them small bouquets of yellow flowers.

Gloria Courser volunteers for the mounted police and said she was there not in opposition to any other messages or rallies in the country but in support of Jackson police. “Talking to some of the guys and gals here in uniform, I heard that they might like to have, in addition to scrutiny, support. Just plain old support,” she said.

Those de-escalation flowers also appeared when a fight broke out at the north end of Town Square.

Protester Kevin Hernandez, a 20-year-old Latino, yelled expletives about President Donald Trump at a 62-year-old white man who walked by donning Trump’s signature “Make America Great Again” red hat. According to Hernandez, the man turned around and asked Hernandez to repeat himself. Hernandez uttered the expletive again and the man punched Hernandez in the head. Two of Hernandez’s friends jumped in to defend him. Police were already on the scene and responded within minutes.

Hernandez was still shaken up when he read his citation for criminal provocation. “Defendant said a slur directed at suspect to elicit response,” the citation reads. In other words, the charge asserts Hernandez used incendiary language to pick a fight with the man.

Hernandez was stunned and did not see it that way. “What about my right to free speech?” he said.

Jackson Police Lt. Roger Schultz told KHOL intent is hard for law enforcement to quantify.

“Sometimes it’s a matter of using your best judgment and taking in the totality of the circumstance as to whether the person is merely expressing free speech or whether they are directing that speech in a manner or circumstance that is deliberately going to incite a fight,” Schultz said.

The older man and Hernandez’s friends were also cited. They are facing battery charges.

Kevin Hernandez, left, talks with the partner of the man that punched him after he yelled expletives about President Donald Trump. “I’m sorry, I’m sorry this happened today,” the woman said. “I hope you enjoy your stay in our beautiful town.” Hernandez replied, “I was born and raised here.” The conversation ended on a surprisingly effusive note when Hernandez told the woman he loved her and her partner. “I love you too; he loves you too,” she said. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

As sounds from that short-lived brawl drifted into George Washington Memorial Park where speakers continued to engage the crowd, Wallace urged people to stay focused on the community dialogue. He was determined to hold a peaceful event akin to the vast majority of protests that have transpired across the country in recent weeks.

The fight, however fleeting, was in sharp contrast to the outdoor discussion and the scene preceding it: hundreds of people walking down Pearl Avenue in silence as a police escort on a motorcycle led the way. Supportive motorists, meanwhile, refrained from honking their horns, instead raising their fists in silence.

Wallace told KHOL his great-grandmother walked in some of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s marches and he wanted this one to mirror King’s iconic demonstrations. “She told me the marches were peaceful. There wasn’t any chanting. They sang, held hands and they protected each other. They showed unity and that’s what I want to replicate.”

Meg Daly contributed reporting.