On May 15, Jodie Pond, director of Teton County Health Department, sat in her office, waiting. All week long she and her team fielded calls from businesses about how to prepare for reopening. But on the big morning of the reopenings, what Pond heard was silence. She wasn’t sure if it was the calm before the storm, or the sound of a new normal.

“It’s kind of like sending your kid off to college,” she said. “You think, ‘OK, I did everything I could to prepare them.’”

Ever since the first public health orders closed local businesses and directed people to stay home, the Teton County Health Department has been working overtime on a thorough and coordinated response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As the county moves into its “stabilization” phase and businesses begin to reopen, the health department has to get back to its ordinary duties—and keep a close eye on COVID. But staffing, funding and public compliance all present challenges for this behind-the-scenes team.

Behind the Curtain

Unlike physicians and hospitals that deal with patients one-on-one, the role of public health is to operate at the population level to prevent disease and improve health and wellness. Their labor usually goes unnoticed when things are going well. But the coronavirus has drawn back the curtain on this vital part of the community, revealing just how much people depend on them.

Pond, who has led the county’s health department for the last seven years, is no stranger to epidemics. She cut her teeth in public health during the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1990s. She worked for the state of Utah running all of the uninsured programs for HIV care. When she started her job, there was one doctor in the whole state doing HIV care. By the end of her 15-year tenure there, she had built a comprehensive system including a sophisticated clinic where patients could get all their needs met.

The health department’s Jodie Pond has spent her career working behind the scenes to launch public health initiatives that keep people safe. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

Doing HIV prevention work in a conservative state like Utah meant flying under the radar, Pond says. At the time, state law prohibited advocating for or encouraging the use of condoms. “We didn’t call attention to our work. We just worked behind the scenes so that people could get the prevention messages.”

Pond says that when she got into public health, a global pandemic was just the kind of thing she hoped never to see. But she knew odds were that she would. “It was predicted years ago that we would see something of this nature. Everybody thought it couldn’t happen. But here it is.”

During the first months of the pandemic, Teton County Health Department has been responsible for contact tracing, public information, testing and business guidance.

Pond and her team developed the county’s “Roadmap to Recovery,” a detailed plan to keep people and businesses safe as they begin to resume normal life. The plan includes a color-coded public health guidance system. Red, orange, yellow, and green indicate the different levels of risk the virus poses in the community. (The county is currently in an orange phase, meaning the COVID-19 pandemic places most people at moderate risk while vulnerable populations remain at high risk.)

For the roadmap to succeed, Pond says Teton County residents must play a part, heeding all public health orders, recommendations, directives and guidelines.

In addition, Pond’s 23-person team manages water safety, restaurant inspections, maternal health, STD testing and prevention, immunizations and a host of other community health-related concerns. Much of their work focuses on low-income families and individuals, with a goal of limiting health disparities.

“It became really overwhelming really fast.”

Since the pandemic hit, the team has worked overtime to deal with the emergency and keep up with their other vital duties.

“It became really overwhelming really fast,” public health county nurse manager Janet Garland said. The 29-year public health veteran and her nursing team are in charge of coronavirus contact tracing. That begins with tracking down and contacting anyone exposed to a person who has tested positive for COVID-19. Public health nurses interview the various contacts, determine their quarantine period, and set them up with resources for food delivery, separate housing, and other support. It’s an intensive process that takes an average of four hours per case.

Garland says they had experience with contact tracing for STDs and foodborne illnesses, but with COVID, “the urgency and volume of cases” far outpaced anything they had ever seen.

Janet Garland, public health county nurse manager, says these days her headset is as much a daily accessory as her face mask. A big part of her job has become contact tracing, which involves hours of phone calls with people that have been potentially exposed to COVID-19. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

While nurses are on the front lines of contact tracing, environmental health staff are in the hot seat responding to businesses’ COVID concerns. Sara Budge heads up environmental health, making sure restaurants, fitness centers, child care facilities and other businesses comply with safety regulations.

When the pandemic hit Jackson, businesses immediately dialed environmental health. Budge and her staff were caught off-guard, knowing that a town emergency ordinance was in the works, but not knowing when it would go into effect. They found out when a distressed business owner called asking for guidance.

“That was definitely a learning experience for us,” Budge said. “We grouped up and in about 20 minutes we had a plan. We started answering calls and turned into a complete call center for local businesses.”

With deep roots in public health and a passion for their jobs, the team had been practicing for a pandemic. In January, the department conducted a discussion-based exercise using pandemic influenza as a scenario to determine what their plan would be for such an event. Leading that effort was Rachael Wheeler, who focuses on emergency preparedness. Her position is funded through a grant from the Centers for Disease Control, which gives states money to increase public health emergency capabilities.

Wheeler says her colleagues have a newfound appreciation for all the drills she directed. Now, those activities really “make sense,” she said. “We are able to put it all together.”

It’s been all hands on deck at the health department, and some staff have been performing tasks outside their normal area of expertise. Nurses from sexual health, maternal health, and immunizations were reassigned to do pandemic response, leaving a skeleton crew to keep up on the traditional jobs.

Garland says their team atmosphere keeps them going. She has plugged staff into emergency roles based on their natural talents. A nurse who excels in organization set up the department’s internal symptom checker system. Another nurse is great with outreach and has taken the lead on providing information to clients.

Navigating such a “stressful, exhausting road” has made it all the more important to know each other’s strengths and just put those people where they need to go, Garland said.

Meanwhile, two new staff nurses are getting their start in nursing during a pandemic. “What are the chances?” they said to Garland.

“Well, since there hasn’t been a pandemic in a hundred years, I guess it’s a one in a hundred chance,” Garland replied.

The Long View

As the department looks to the future, staffers know their commitment has been instrumental in the community’s effort to reduce infection rates. “We have this great sense of relief that we made it out of the response phase. We flattened the curve and kept hospitalization down,” Pond said.

Coronavirus cases in Teton County plateaued a few weeks ago. As of May 19, there were 69 confirmed and 31 probable cases of COVID-19. Protecting the valley’s limited medical infrastructure has been a key concern and with 13 total COVID-related hospital admissions and zero of those patients currently at St. John’s Health, the hospital remains in good shape, said Dr. Paul Beaupre, CEO of St. John’s Health. Meanwhile, the majority of COVID patients, 92, have recovered.

Early advocacy from health officials like Pond urging local leaders to proceed with caution was impactful.

In March, Pond addressed officials about the new coronavirus weeks before the first confirmed case in Teton County. She told them COVID-19’s arrival was “not a question of ‘if’ but ‘when.'” Elected officials heeded the call and voted shortly after that to cancel large-scale events, like Rendezvous Fest and Hill Climb, that have historically drawn tens of thousands to the valley. Teton County continued to enact measures that were more stringent than statewide directives with Teton District health officer Dr. Travis Riddell leading the charge and Pond offering key input.

They were paying close attention to Blaine County, Idaho, home to Ketchum and Sun Valley, where health officials traced an explosion in cases back to a few large events that drew visitors from coronavirus hot spots. Blaine County has roughly the same population as Teton County but its per capita infection rate is higher than New York City’s and the crisis there shut down the local hospital.

Teton County managed to escape such a fate.

Still, Pond isn’t resting easy, nor does she think the valley is in the clear. “It’s a marathon. We still have stabilization to get through,” she said.

For the stabilization phase to be successful, the health department needs funding in addition to what it receives from Teton County. Its current budget deficit is close to $350,000, which Pond says is as spartan as she can make it. Because nearly her entire staff has been working on COVID for two months, when they turn back to their usual jobs, they will need additional staff in place to tackle COVID. The money would cover the salaries of six new staff members, as well as critical materials and personal protective equipment.

Pond has been waiting on word from Gov. Mark Gordon about whether county health departments will receive any federal money to continue their COVID-related work. On May 13, Gordon announced that he was allocating $15 million of federal relief money from CARES Act funding to the Wyoming Department of Health. Whether any of that money will be directed to county health departments remains to be seen.

Gordon’s spokesperson did not reply to a request for comment.

“We’ve been told they did earmark some of the money for county public health, but I have yet to see it on any bills,” Pond said.

Rep. Mike Yin, D-Jackson, said he is concerned as well. “If we want to stay open, do contact tracing and prevent community spread, we need these funds,” Yin said. “I’m hoping the legislature will do what is needed and put money into county programs.”

Pond says time is running out and she needs to know about funding by next week. Without the money to support continued contact tracing, personal protective equipment and other elements of the COVID response, crucial services will fall to the wayside. “Somebody will have to tell us if they want us to do COVID or restaurant inspections, COVID or family planning, COVID or immunizations,” Pond said. “We can’t do both.”

“It’s a marathon. We still have stabilization to get through.”

Burnout is also knocking on the health department’s door. Budge says they are working long hours, making guidelines and trying to come up with processes that make it easier for people to adapt in the age of COVID. But it’s not getting much easier for her and her colleagues. “So, the fatigue is definitely starting to kick in.”

For her part, Garland often finds herself working evenings and weekends, keeping up on administrative work as well as handling contact tracing.

Meanwhile, the lines between Pond’s work and home life have also blurred. Almost every evening at 9:30 p.m. she speaks to district health officer Riddell. The two continue to work closely on the county’s health orders and variances. They study the metrics in the health department’s Roadmap to Recovery, compare previous case data and look for trends. Riddell makes the final call on health orders that he then submits to the state—like one he is working on now that would require all people to wear face masks in public—but the health department plays a crucial role in the process, providing him with research on myriad issues.

Officials say health orders are often necessary when messaging alone isn’t enough. Encouraging people to wear masks in public, for example, is central to the health department’s current public campaign. But a glimpse around town shows a lot of folks are unconvinced.

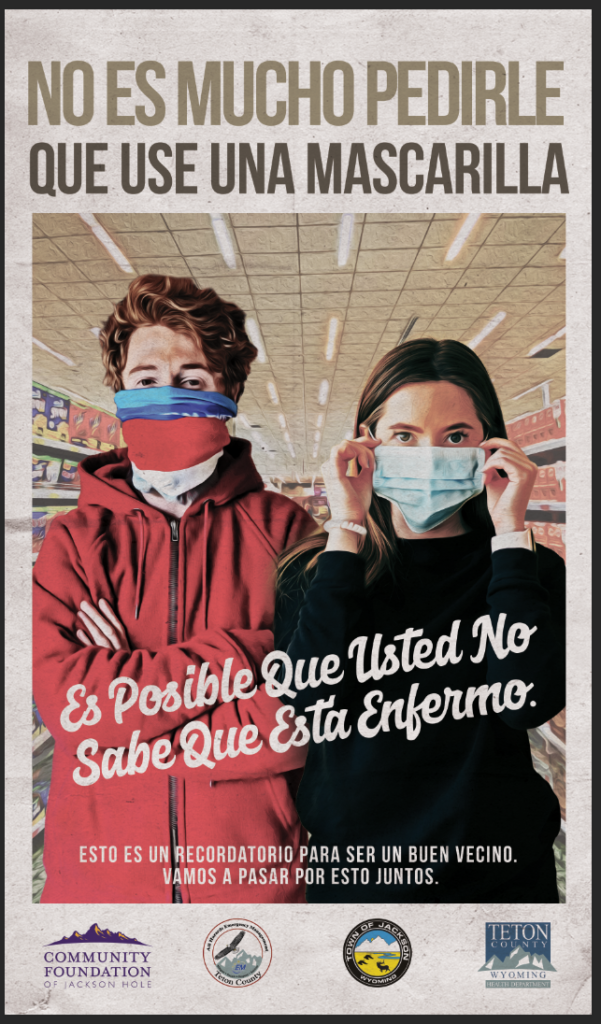

- Teton County Health Department’s latest efforts to reduce COVID infection rates include a campaign encouraging all people to wear masks.

- The department has a Spanish interpreter on staff, Shelley Rubrecht, who helps get such messaging out to the Spanish-speaking populace.

In the beginning of the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control was not recommending masks for the general public, in part to prevent a run on N95 masks that should go to first responders and health care workers. However, that advice has shifted. The CDC and Teton County Health Department are now recommending people wear masks in public.

Pond says the new messaging focuses on recent science. “There’s new evidence that shows that if 80 percent of us wore those it would be similar to herd immunity,” she said, referring to when the majority of the population becomes immune to a disease. Some individuals may still be at risk when herd immunity is reached, but the group overall has protection. With the novel coronavirus, masks wouldn’t eradicate the virus. But they would decrease its ability to spread. As long as most people are wearing masks, you could feel safe going to the grocery store and living somewhat normally, Pond said. But only a vaccine will ensure total immunity.

The idea with masks is: “I protect you, you protect me,” she said.

Whether it’s masks or other protective measures, Wheeler hopes people will recognize that the health department is learning new information all the time, just like the general public. In addition to emergency preparedness, she is responsible for public information and is learning how to be nimble with each new study that emerges. “This is a constantly changing event. We are trying to be as transparent and quick to respond as we can. So, messages may tend to shift over time.”

As the health department pivots back to their regular jobs while still staying attuned to everything coronavirus, several staff members said they balance their stress by spending time with family. Wheeler dotes on the infant she and her husband welcomed into the world five months ago. Garland relishes her college-age kids being at home and cooking for her. And Budge is attempting to heed advice from her 18-year-old daughter who graduates in June: “Mom, just embrace the COVID weirdness.”

Budge’s advice to her daughter as well as the community: “Wash your hands!”

Robyn Vincent contributed reporting.