Update: Since KZMU’s story aired on Utah’s energy royalty grants, the state’s Seven County Infrastructure Coalition has suspended their Book Cliffs highway proposal and withdrawn their right-of-way application to the Bureau of Land Management. Grand County commissioner Mary McGann says she looks forward to working with the coalition on projects that will help her constituents.

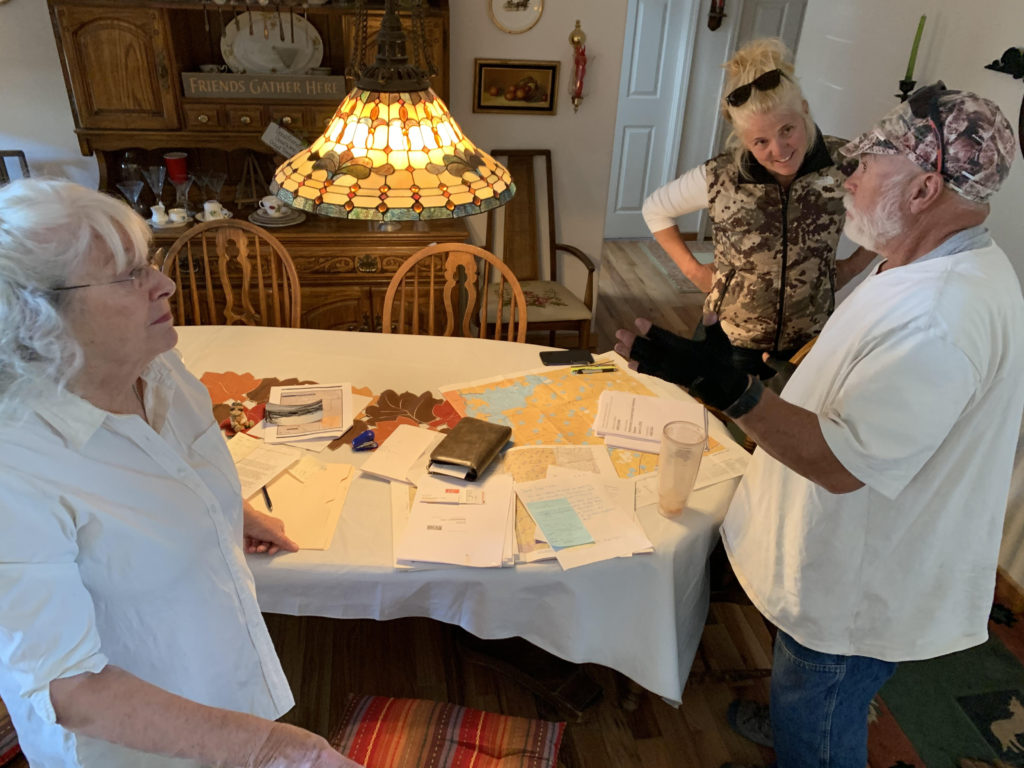

You can find Lee and Debbie Elmgreens ranch at a shrubby fork in the narrow canyons of the Book Cliffs. On a recent fall day, the greens have a map of southeastern Utah spread across their dining room table.

Lee Elmgreen is reading a new report by the Bureau of Land Management. It’s a 1300 page study of a plan to put a massive road in their backyard.

“The scope of this work included a review of available information,” Elmgreen said. “And a one-day visual windshield reconnaissance of the project”

The 35-mile highway would carve through the enormous stretch of undesignated wilderness that abuts their property. The Elmgreens worry the road is unrealistic in the tight and steep gorges. They also worry it will harm ancient petroglyphs painted on the canyon’s walls.

“All you got to do is drive this road and drive it slow enough to appreciate the drive,” Elmgreen said. “The vistas, the canyon structures, the rocks, the rock art…is awesome.”

Debby Elmgreen, Lee Elmgreen and Grand County commissioner Trisha Hedin study plans in October for a 35-mile highway through the Book Cliffs area in southeastern Utah. (Justin Higgenbottom/KZMU)

An interstate highway through the Book Cliffs was first floated over three decades ago in 1988. Now a coalition made up of seven Utah counties is reviving the idea. The coalition’s goal is to identify revenue-producing infrastructure projects in the region. They say the highway would be a boon for recreation, but critics say the estimated $418 million price tag will likely be paid in part by Utah’s Permanent Community Impact Fund Board or CIB. The CIB collects royalties and rent from oil and gas mining on federal lands and turns it into grants and loans for communities impacted by industry.

The money funds projects like parks, cemeteries, and recreation centers.

Over a decade ago, the CIB loaned Moab $4.8 million to construct this Aquatic and Recreation Center. But the statewide reserve has also funded nearly all of the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition’s projects. And Wendy Park says that’s a troubling trend. She’s a senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity.

“The CIB is supposed to be an independent board that allocates money to communities that are impacted by mineral development,” Park said. “The seven-county infrastructure coalition has received 10s of millions of dollars for fossil fuel development projects that only exacerbate the impacts of mineral development.”

Last year, the CIB gave $27.9 million to the seven-county coalition for a project that would help transport oil in the Uintah Basin by rail. That’s being challenged in court by Park’s group.

The board also spent $9 million for the Leland Bench Road project near Vernal, Utah. Also through the infrastructure coalition. A government audit found that the project was more about economic development than offsetting the impacts of mineral extraction, the CIB’s mission.

“We’re in a pandemic right now,” Park said. “We’re in an economic downturn, communities are hurting for funds to provide services. And instead of funding these essential public services, this money is going instead to funding an oil railway and the book cliffs highway.”

The CIB has tried to make funding decisions more consistent. CIB staffer Keith Heaton says they even developed an algorithm to help.

“It’s not that the computer shoots out a decision based on inputs, but it gives the board parameters of where they should be in making their decision,” he said.

Those parameters can include how much land is owned by the federal government and so unavailable to taxing by communities. Or it can take into account how much extraction exists. But the board still has the final say. That means they can make exceptions to projects that are not recommended by the funding tool.

Critics of the CIB point not only to controversial projects, but community needs not getting attention. Mary McGann is a commissioner in Grand County Utah where 90% of land is owned by the federal government.

“Bike paths to make it safer for people to come to Spanish Valley into Moab,” McGann said.

Visitors are attracted to nearby national parks but the town has real needs for projects where tourism dollars fall short. She says they’ve been trying to improve drainage for example, for years. Flash floods north of town in Moab have ruined yards.

“The courthouse, people literally have offices in closets,” McGann said.

McGann says that grants from the CIB are rare nowadays. Now it’s largely loans. She says some in local government are even worried about getting on the board’s bad side. Five years ago there was a fight to fund an overdue jail renovation in her County. McGann blames politics.

“We have been bit,” she said. “We’re under their thumb because we do rely on getting CIB money.”

The economy is uncertain in Utah. So are oil prices. But population and visitor numbers are exploding in places like Grand County. After the CIB got dinged in the recent audit, McGann suspects changes are coming to how extraction royalties are spent.

In mid-December, the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition withdrew their application for funding of the Book Cliffs Highway. The project is once again on hold for now. But McGann says the decision opens the door for collaboration on future projects in her county’s interest.

With the recession an outbreak away, communities will need investment more than ever. And that means the cost of projects like the Book Cliffs Highway has increased.

This coverage is part of a new collaboration, reporting on the impacts of fossil fuels, coordinated by the Rocky Mountain Community Radio Coalition