Jackson resident and writer Kevin Grange has dealt with almost every emergency situation imaginable in his years working as a paramedic in Jackson Hole, Los Angeles, Yellowstone and Yosemite. Grange recently released a new memoir called “Wild Rescues,” and he joined reporter Will Walkey in the KHOL studios to discuss the challenges of emergency care in the backcountry, as well as the mental health toll of being a paramedic. As a warning, this interview includes discussion of suicide.

The following transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Walkey: “Wild Rescues” is obviously a personal memoir of yours. But you also say in the book that it’s important that you get the work of wildland paramedics and wild EMS [Emergency Medical Services] people in the spotlight. Why was it important to you to tell the stories of wilderness medicine to a general audience?

Grange: I think it’s important because about 70 percent of EMTs [Emergency Medical Technicians] and paramedics work in a rural setting; however, in every movie, book, TV show, it’s always set in an urban setting. So, there was a whole side of the emergency medical services and fire departments that had never been portrayed before. And then it does have a local slant in that we are fairly remote here in Jackson Hole and Grand Teton, and the level of care here is first-rate despite all the challenges of weather and distance to the nearest, you know, Level Two Trauma Center in Idaho Falls. In this little pocket of Jackson Hole, we have just amazing providers kind of adapting and overcoming.

Walkey: What are some common challenges that you would face when in a wild setting as opposed to in Los Angeles, where I know you worked as well?

Grange: One setting is just the staffing. You know, in the city, you generally arrive on scene with a fire engine full of four firefighters and two on the ambulance. You have six people on scene. Whereas here, you know, oftentimes you might just arrive with your partner. Or, when I was with the park service, sometimes it would just be me on the ambulance by myself.

And there is the weather and the environment and reaching the patient. You know, they talk about the golden hour. You want to get the patient to definitive care within 60 minutes from the time of injury, which is hard when it might take you 60 minutes to get to the patient from Jackson or in Grand Teton [National Park]. So, the clock is always working against you out here.

Walkey: I think my favorite story in the book was that first wild rescue that you did in Yellowstone.

Grange: Yeah, that was for a car that had just gone off the roadway and down a steep embankment into the woods. And another challenge with wilderness EMS is where are we responding? You know, in a city there’s an address and you know right where you’re going. In the national parks, whoever calls it in, if they have cell service, might be like, ‘Yeah, the accident is around that bend, near that tree or by that rock.’ And of course, that doesn’t really narrow it down.

And so then we had, I think, about a 50 minute transport time to get to the patient. So again, we’re already behind the curve in that golden hour. As we were driving there, we encountered a huge herd of bison on the road, which, you know, wouldn’t leave. We tried the sirens. In that case, I had to imitate a mountain lion over the P.A., which actually surprisingly moved the bison. And that call just illustrates that, in this remote and rural setting, there’s always reversals. There’s the Plan A, which often doesn’t happen due to circumstance, and then there’s Plan B, but oftentimes you’re improvising to make a Plan C happen.

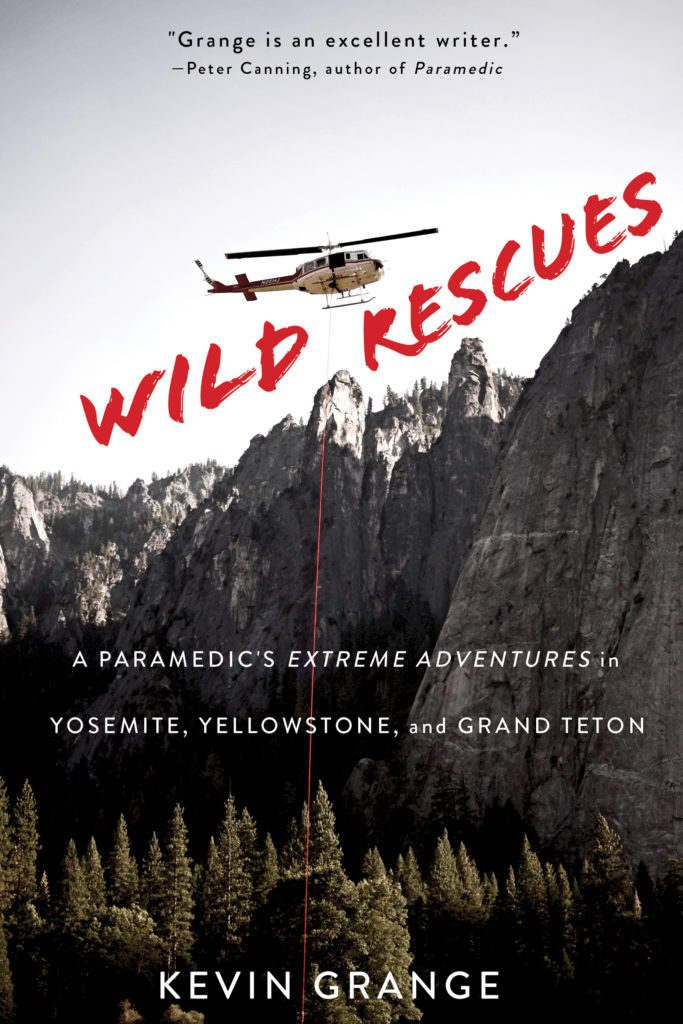

“Wild Rescues” is Grange’s third book. The memoir is available now in both local bookstores and online marketplaces. (Courtesy of Kevin Grange)

Walkey: You interact with all sorts of people in Yellowstone and Yosemite—literally every type of traveler it feels like. I’m curious if the type of person that you’ve been interacting with in the parks has changed since you started working in wilderness EMS, especially since the pandemic began.

Grange: I would say, you know, the numbers of tourists have increased. There is a danger of people just loving our national parks to death. And I know last year, I think September and October were the busiest months ever in Grand Teton. And with the pandemic, people sought out and fled to these wilderness areas as a way to social distance. But in a way, they kind of brought the crowd that they left from the city with them. So it was a challenging and unique summer last year. And I’m sure this year will be the same.

Walkey: You mentioned the fact that wilderness medicine is becoming more popular. With more people coming to wild places, there’s also a lot more people who want to help people in wild places. I’m curious as to why you think that is. Why is wilderness medicine becoming more popular?

Grange: Yeah, it’s going through a huge surge in popularity, I think, because people are embracing far-flung travel more. And then also the field of wilderness medicine—which one doctor describes as adding another room to the ancient house of medicine—it’s kind of grown in where you can provide it. What we found during some of these, you know, Hurricane Katrina—these large natural disasters that cut off power and utilities to city centers—they’re almost becoming wilderness in nature. And so some of the same challenges that we face out here, you’re facing in a city that’s maybe cut off due to a flood or, you know, the power’s cut off. So, it’s really applicable to anywhere you work. And then once you have that wilderness medical mindset, you are able to kind of improvise and work in all these different environments.

Walkey: This year has been stressful with the pandemic. I know you’ve been working with Jackson, and that’s slightly different from working in Yellowstone every day. But how has it been with the pandemic working in EMS?

Grange: It has been stressful. I think one blessing that we had is, you know, we had job stability. In fact, our job got busier, whereas a lot of people were out of work. So we’re very thankful for that. And then when we go to work, like I said, we have that first responder family. So, we were lucky not to have some of that isolation that a lot of people had.

And it was certainly challenging. The number of calls went up. And, you know, just wearing all the personal protective gear and just the stress of COVID and not knowing in the early days of how it’s transmitted and who has it, that was definitely stressful. And then we saw a large sort of increase in mental health type of complaints—you know, overdose, people drinking a lot more—so we saw a lot of the effects of COVID as much as treating the actual disease.

Walkey: You opened up a little bit about some of the mental health challenges that you faced while working in Teton EMS. Can you just talk a little bit about that—some of the specific mental health challenges that you faced and then maybe how you were able to overcome them a little bit?

Grange: Definitely. First responders are great at providing help, but historically, we haven’t been good at asking for help. In the book, I say each first responder inhabits their own haunted house because of these traumatic calls that you run. They begin to kind of stack up internally. And if you don’t deal with them, you know, there can definitely be some negative effects as far as, you know, your well-being and your relationships. And so I ran a couple of tough calls in the book. You know, unfortunately, the national parks do attract a lot of people who do want to commit suicide. And so I did run that call and that sort of put me over the breaking point for me personally. And it brought up some of the other traumas.

I would say it was like on the lower end of post-traumatic stress, so I was able to listen to podcasts and talk to coworkers, and I found journaling very helpful. And the best thing was just getting outdoors and being in nature. So, you sort of get your own tips and tactics to deal with these tough calls. And it’s just important to sort of discipline yourself to do them after the tough calls. The goal is just transitioning that post-traumatic stress to post-traumatic growth.

Walkey: Switching gears, national parks have been called “America’s best idea.” You call them the “highest expression of democratic ideals.” How has your experience as a paramedic led to your thoughts on national parks as America’s best idea?

Grange: So, I think of the National Park Service as sort of like the heart of America. It’s the beating heart of America. The awesome thing about EMS is that, you know, we enter a scene and a call and our thought is ‘No one is beyond saving,’ and we’re going to do everything we can to save a life. And that’s irrespective of someone’s, you know, race, color, creed, socioeconomic status. And that’s this American idea that every life has value—every life is sacred. And it’s also sort of connected to the national park idea that everything within the universe is connected and has value from, you know, this river to that stone to that forest. So there’s a great overlap. And then, you know, democracy and the national parks is just this American idea that has spread throughout the world and created a lot of good.

If you or a loved one is experiencing suicidal thoughts or an emotional crisis, help is available 24/7 at the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 800-273-8255. Community members can also sign up for six free mental health visits at a local counseling center through the Mental Health JH initiative.