Jon Stavney lives in Eagle County, Colorado, which is home to both Vail and Beaver Creek ski resorts. He’s served on town boards and was a county commissioner there, but recently, he’s taken on a new position.

“I’m executive director of the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments. It’s a mouthful, but we represent local governments,” Stavney said.

Part of Stavney’s job is to communicate with several resort communities similar to Jackson Hole, like Aspen and Breckenridge. He also took on a new task this year: helping document changes that have occurred in those areas since the outbreak of the pandemic in March 2020.

“I think when it first hit a lot of our communities, people thought, ‘This will be interesting. We’re going to have the place to ourselves,’” Stavney said. “Like the 2008 crisis, housing prices may go down and people are just not going to want to be here. Well, it turns out people have a lot of options when it comes to isolation.”

Jon Stavney is executive director of the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments. (Courtesy of Jon Stavney)

Stavney started hearing anecdotes from county commissioners about visitors coming to mountain towns and staying longer, and demanding different services than many locals. So, he talked with real estate agents, conducted surveys and crunched the numbers to get a fuller picture of just how much the pandemic is affecting mountain towns in six Colorado counties. His research culminated in the 70-page Mountain Migration Report.

What Stavney and his partners found is that many communities are undergoing accelerated changes unlike anything seen over the past decade, especially when it comes to housing.

“There’s a sense among some locals that the housing issue is just the same as it ever was. One of the things that we found out is, yes, but that’s not quite the case,” he said.

For example, many new residents and part-timers are entering the rental market, rather than purchasing real estate. That’s raised the average price of some apartments and townhomes by anywhere from 20-40%.

“You think of renters as being somebody who’s going to be there for a year or more, which is probably somebody who’s going to probably have a local job. Well, many of them have work that’s attached somewhere else,” Stavney said.

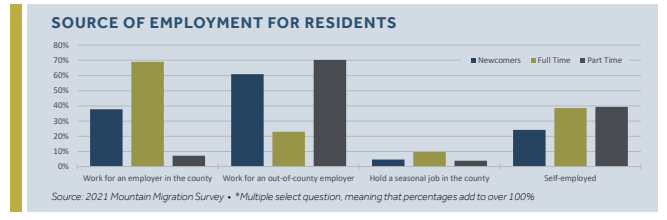

60% of new residents that moved during the pandemic to the Colorado mountain towns studied work for an employer located outside their resident county, compared to just a quarter of the local population in those places. 70% of those newcomers also make over $150,000 a year.

“Lo and behold, you know, the people that also need help are nurses and doctors and people earning what locally looks like a lot of money. But when they’re competing with these folks coming in, it’s a different game,” Stavney said.

60% of newcomers surveyed as part of the Mountain Migration Report work for an employer outside of their resident county. (Mountain Migration Report)

Of course, Stavney has been aware of these trends for a long time, but like so many shifts across the U.S. last year, COVID accelerated and cemented them. Real estate, for example, is poised to remain on a bull run. And part-time residents are also doing things differently.

“They’re not visitors in the classic visitor sense,” Stavney said. “They’re really seeing themselves as residents of the community. And in a couple of years, a large number of these people potentially are going to be long-term residents.”

Part-time residents will spend 30% more time in their vacation home over the next few years, according to the report. That’s good in some ways for local tax collectors, nonprofits and construction industries. But it also makes it harder for local workers to find a place to live.

“Workers are people. They come with families. They need a place to be. You can’t just stack them up like cordwood,” Stavney said.

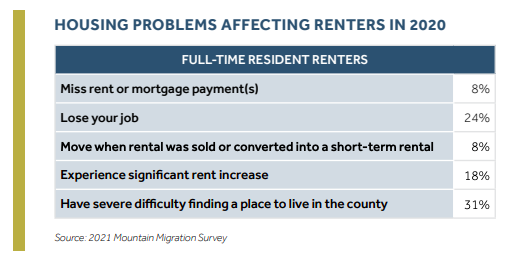

18% of surveyed renters said they saw their monthly rates go up in 2020, and 31% expressed having “severe difficulty” securing housing. Stavney hopes local officials see his report and realize they need to take radical action.

Renters in many of Colorado’s resort communities are often living in unstable housing situations. (Mountain Migration Report)

“They’re going to have to make some changes in policy. And in some cases, I think aggressively pursuing, even more than they have before, housing in whatever form that takes,” he said. “They’re going to have to shake the tree more than they have before.”

Stavney also said those changes are sure to meet healthy resistance from people who suddenly have to live in denser neighborhoods or have their views obstructed.

“They are special places. And there’s a reason that many of us who are in these places have gravitated there. And so, change needs to respect that,” he said.

But change also needs to respect the needs of both newcomers and local workers. Stavney said that’s going to take courage from electeds to be bold and think outside the box.

“I think all that incremental stuff is good, but it’s not going to address this,” he said.

Mayors and county commissioners have already started referencing the Mountain Migration Report, partially to signal how quickly their communities are shifting and in what ways, and partially to show other mountain towns: You’re not alone.