The recent discoveries of two mass graves containing the remains of hundreds of Indigenous children in Canada has disturbed both our northern neighbor and the U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland also announced the launch of a new effort last week to investigate the loss of human life and lasting impact of former federal Indian boarding schools, which aimed to strip Indigenous children of their Native languages and culture.

KHOL News Director Kyle Mackie discussed the generational trauma inflicted by the schools with Superintendent Frank No Runner of St. Stephens Indian School, a former boarding school located on Wyoming’s Wind River Indian Reservation. The following interview transcript and audio have been edited for clarity and brevity.

KYLE MACKIE: Superintendent Frank No Runner, thank you so much for joining us today on KHOL.

FRANK NO RUNNER: Thank you. Happy to be here.

MACKIE: Can you tell us a bit about the St. Stephens Indian School on the Wind River Reservation?

FRANK NO RUNNER: Well, St. Stephens Indian School is a BIE [Bureau of Indian Education] tribally controlled grant school, and it works with both the Northern Arapaho Tribe and the Eastern Shoshone Tribe, rotating every other year. And we currently serve about anywhere from 250 to 260 kids, all tribally enrolled kids. It’s about 99% Native American. And we have a staff of over 70 people to support the children that come to our school.

MACKIE: And can you tell us about the history of the school there? I understand that the school was originally founded by a Jesuit priest from Buffalo, New York—which, funny enough, I actually moved out here from Buffalo, New York—and I believe it was a boarding school until the late 1930s?

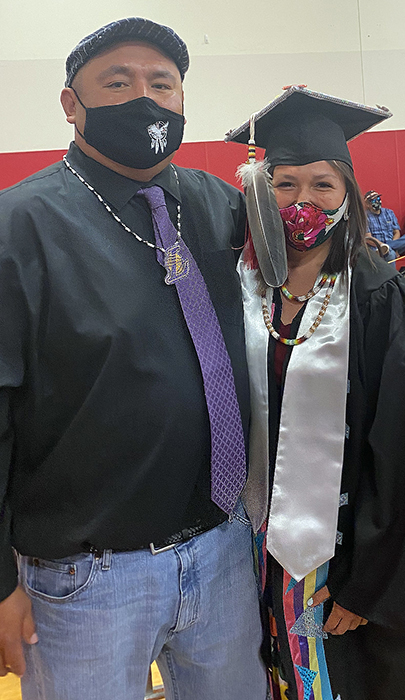

Superintendent Frank No Runner poses with his niece, Mariah Juneau, during her 2021 graduation from St. Stephens Indian School. (Courtesy of Frank No Runner)

FRANK NO RUNNER: Yes. So, it was founded in 1889. So, the school has a rich tradition and history from that long, long period. So, it’s been here since 1889. And it was a boarding school. And so, they finally became—I think they got their high school in the ‘50s or ‘60s, I believe. And in 1975, the mission finally gave the school back to the tribe.

MACKIE: Obviously, this is something that is hugely important and a lasting legacy among Indigenous communities. This legacy of boarding schools. But for many of our non-Indigenous listeners who might not be so familiar, can you tell us a bit about that and what the purpose and the function of these schools was?

FRANK NO RUNNER: I’ll just tell you a personal experience first. I’ll start off with that. I was raised by my late grandmother, and also my late great uncle. My grandma raised me because my parents were too young when I was born. So, my grandmother raised me from a little boy. As a little kid, on Saturday mornings, we would wake up to the smell of breakfast and you’d wake up to hear them speaking our Blackfeet language. And, you know, sometimes as a kid, you lay there, you’re half asleep, and you can still hear them talking their Native language. You don’t understand it, but you know it’s a part of who we are. But once us kids would get up there, it was just three of us that lived with my grandma—me and my sister and my brother—once we would get up, they would stop and they would just start talking English. And so, when I got older, I finally asked my grandmother, like, ‘How come you guys never teach us your language?’ And the old man that lived with us and also my grandpa, they instructed their kids not to teach them our Blackfeet language and culture because of what happened in the boarding schools to them with their experiences.

They didn’t want the trauma that they experienced in that boarding school [to happen to us]. I mean, it basically trained them, I would say, or put fear in them that they would not want us to learn that because we were still going to schools in the ‘80s. And I think at that time, some of the teachers, the principals still had a paddle in some of those schools. And so, they just didn’t want us to do that. So, they never taught us that. And so I grew up not knowing my language and not knowing a lot of my culture. And as a 40-year-old man I’m finally taking an interest in it. And I’m trying to learn much Indigenous methodologies as I can about not only my culture, but also the Native culture in general. So, that’s what I’m doing right now.

MACKIE: Okay, so you know, sadly, we’re speaking today because over the last several weeks, there have been these horrendous discoveries of huge unmarked mass graves of Indian children on the site of former residential schools in two different Canadian provinces. And then there’s also been this commitment by Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland. I wonder, as a Native educator and superintendent, what it’s been like seeing this news and, you know, how you’re moving forward with this new commitment from the U.S. government, at least?

FRANK NO RUNNER: Well, you know, being a doctoral student, there’s a big debate going on in the United States right now about critical race theory. And one of the critical race theories that I’m currently looking at studying in my dissertation is Tribal Critical Race Theory. And that’s what looks at these injustices that happened in the past to the minority people. I don’t think it can be forgotten. I think it should be taught. I don’t think it should be [over]looked. I’ve heard professors and also other Native American leaders, such as Denise Juneau, who’s a well-respected American Indian leader, basically say that we should—that historical trauma happened and we as Native people should try to move past it. Move forward. But I think before we can do that, I think that healing needs to take place, and just the understanding of our history of what happened to our Indigenous peoples, because like the boarding school trauma really affected my life. And I really wish that I could be a fluent Blackfeet speaker today.

MACKIE: I understand that at one point there were four boarding schools operating on the Wind River Indian Reservation. So I wonder, from your perspective, what the legacy is there locally among the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone tribes that live there? And, you know, this impacts your students, I’m sure, down through the generations.

FRANK NO RUNNER: Yes, it does. It’s basically a generational trauma that’s been passed down. And a lot of the ills today that we see on the reservation are passed down through all that generational trauma. You know, the boarding school legacy is kind of an embarrassment to the United States, I would say. You know, kids were just taken from their families, and like my mom—my grandmother, I call her mom, sorry—but my grandmother, she was taken from the Blackfeet reservation and she was moved eight hours away. And that’s in the early ‘30s. You know, back then, people didn’t have cars, so it was hard [for parents] to see their kids. And it was really sad that she was taken away from her parents. And while she was in the boarding schools, you know, her mother died. So, she never really got to know her mother growing up. So, there’s just a lot of different stories from different people that I think need to be heard, or just need to be told.

I think that’s one way to heal stuff, is just to talk about it and find out a way how we can heal it so we can help our future generations learn from our past mistakes and move on and make a better world for our Indigenous children—and not only Indigenous children, but for every child in the U.S.

MACKIE: Well, thank you so much for your time today, Superintendent Frank No Runner. We really appreciate you joining us today on KHOL.

FRANK NO RUNNER: Thank you. I was happy to be here.