At 22 years old, the late Angus MacLean Thuermer, father of Wyoming journalist Angus Thuermer Jr., witnessed something that changed the world forever. It was 1939 and the recent college grad was in Germany to refine his German language skills. While he was in Berlin, Thuermer got a job with the Associated Press.

His editor there decided to send the young reporter east to Gleiwitz, a German town bordering Poland. It was two weeks before Hitler invaded that country. The invasion set World War II into motion and Thuermer was nearby to file one of the first eyewitness accounts. Last month marked the 80th anniversary of that fateful invasion.

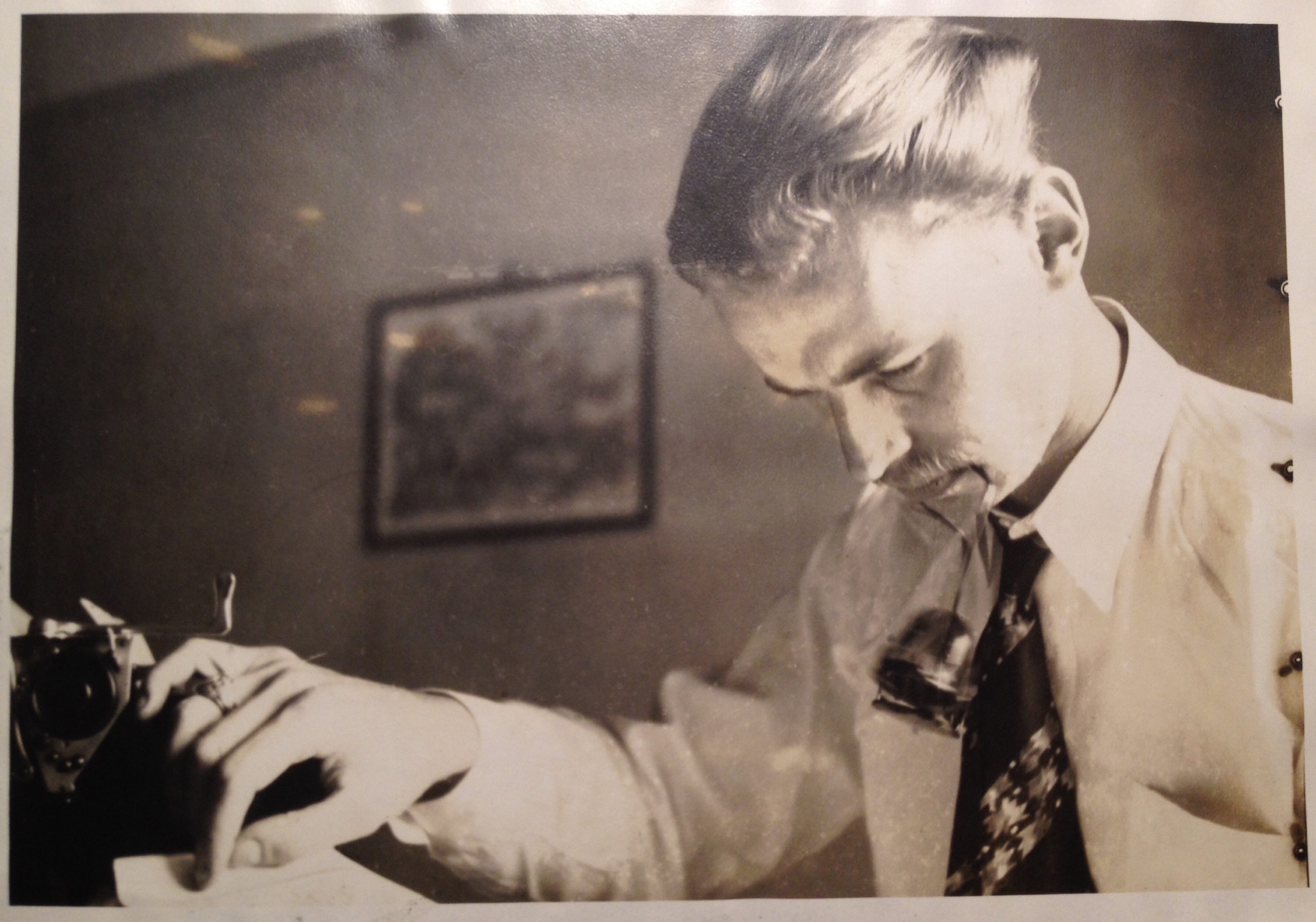

“I wanted to bring this story back to life on one of the anniversaries,” Thuermer said. He has been sifting through his father’s stories and photographs for several years. Recently he began sharing that work on social media. One thing that struck him during that process was the vivid details his father included in his stories: the troops marching in front of his father’s hotel; the types of armaments they carried; that their division insignias were covered up; their chrome bumpers painted black and their license plates changed so people wouldn’t detect where they had come from.

What made his father’s reporting even more striking was how it cut through the noise of disinformation propagated by the German press at the time. “There was an incredible propaganda war going on in the newspapers with reports of Polish atrocities against German-speaking citizens in Poland,” Thuermer said. “All of this was being stirred up as a justification for the ultimate invasion of Poland.”

MacLean Thuermer was also ahead of the pack.

As soon as he arrived at Gleiwitz, he filed a story that described the increasing numbers of German troops that had descended on the German border town. He reported a turnout of 111,000 troops. “That’s 10 divisions of troops on the border two weeks before the war,” Thuermer said. It was a fact that was overlooked by other journalists and media outlets until the London’s Telegraph ran a banner headline about the presence of troops at the border just two days before the invasion.

In those days leading up to the war, MacLean Thuermer hired a taxi and drove into the night along the border between Germany and Poland. The scenes he witnessed suggested a dark chapter was on the horizon: “roads being mined, roadblocks, ashen-faced troops marching.”

The next thing MacLean Thuermer saw indicated he might be in trouble. A German officer stepped out from behind a tree, put up his hand and asked the taxi to stop. The taxi driver slowed down and then made a brazen decision to step on the gas. Thuermer said “they zoomed back to Gleiwitz,” and the young reporter ran upstairs into his hotel room where he filed a story just a few hours before sunrise.

“Then he called the front desk and said, ‘If you hear any explosions or bombs going off, wake me up.’”

But the war did not start that day. Britain had just entered a mutual defense pact with Poland which complicated the Nazi plans in Italy, Thuermer explained. “Mussolini also had some reservations about being able to contribute to a sustained campaign.”

A few days later, however, the war did break out. Thuermer described that day as “somewhat anticlimactic” for his father. In other words, in Gleiwitz, there weren’t many indications of conflict. But with his account of wounded German troops returning to Gleiwitz from the front lines, the fledgling correspondent managed to capture “some sort of texture of actual war” that was largely missing from other stories across the globe.

“It makes me wonder where in the world today there might be a 22-year-old reporter or photographer and who is supporting her.”

MacLean Thuermer reported from all over Hitler’s Germany for the next two years until German authorities arrested him and other journalists and diplomats in December 1941, when the United States entered the war. He was released six months later with his stories intact.

“He kept them after he was arrested by the Gestapo and interned for six months in Germany. And he brought them back to the United States and saved them in a file,” Thuermer said. Many years later, Thuermer’s sisters submitted them to the Associated Press.

To revive his father’s stories and share them with a new generation, Thuermer approached this project much like the longtime journalist approaches many assignments: with careful curiosity. He combed through dozens of pages of his father’s typed and handwritten stories, studying sentences and filling in missing words. The process was contemplative. It was one that gave him a greater window into his father’s identity and into the history his father captured on the page. For the Wyoming journalist, it also underscored the value of journalism and its fragile state today.

“It makes me wonder where in the world today there might be a 22-year-old reporter or a photographer and who is supporting her. Is she in Hong Kong? Is he in Afghanistan? In today’s media landscape, where newsrooms are dwindling in size, where resources appear to be drying up, where the fourth estate itself is under attack, who’s got the back of these reporters in the field?”

MacLean Thuermer’s experiences as a war correspondent set him up to be an astute observer of people and events on an international scale. After his time reporting in Germany, he joined the U.S. Navy. He went on to work for the Chicago Associated Press for a brief stint before joining the Central Intelligence Agency. At the CIA, MacLean Thuermer became a top-ranking official working all over the globe in locales from Munich to New Delhi.

“There’s probably no difference between what he was writing and observing on the border of Poland and the reports that he may have filed and the observations he may have made for the Central Intelligence Agency, except as a reporter, he wanted the whole world to know,” Thuermer said.

MacLean Thuermer died nine years ago at the age of 92 near Middleburg, Virginia.

When asked what else Thuermer would want to know about his father’s WWII dispatches, he replied as any good journalist would: quite simply, he would want “more details.”