Minimize harm. That tenet guides the work of trained journalists everywhere. It means weighing the public’s need for information against the potential harm our reporting could inflict on others—sources or readers.

Minimizing harm is enshrined in the Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics. It reminds journalists of our noblest pursuits: to seek truth and report it, to act independently, and to be accountable and transparent.

Many of us begin studying this creed on our first day of journalism school. It cements in the hearts and minds of fledgling journalists the gravity of their new vocation.

The SPJ code then migrates with us into our first newsrooms, becoming a beacon as we face increasingly difficult decisions about the people and issues on which we report. Mine is printed on a frayed double-sided bookmark—a memento from a journalism course where I studied stories that hewed closely to the SPJ code and ones that violated it.

Today, no matter where that tattered bookmark is, I keep its message close.

I found myself a few days ago invoking the SPJ code to an 18-year-old aspiring reporter. I told her that many journalists see themselves as public servants—we feel a duty to provide our communities with information that can help them to lead better lives. And we want to shed light on problems so they can be addressed, as Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalists Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey wrote in their book “She Said.”

Many journalists now feel those duties on a cellular level.

“In a public health crisis, the media has the power to save lives,” wrote Genevieve Hutchinson, senior health advisor at BBC Media Action, and Jacqueline Dalton, BBC senior producer and trainer in humanitarian programming.

In a manual for journalists reporting on health emergencies, Hutchinson and Dalton remind us that during a crisis, the media can swiftly send life-saving messages to the masses. “It can provide people with critical information from trusted sources so that they know what is happening, how to protect themselves, and when and how to seek treatment and support.”

Conversely, the writers warn that a dearth of accurate information during such emergencies could lead to rumors and disinformation that sow “panic and chaos.” In the absence of accurate info, “practices that put people at even more risk” proliferate.

“In a public health crisis, the media has the power to save lives.”

But what happens when the very institution tasked with connecting the public to life-saving information becomes a vehicle for disinformation?

That brings me to a recent article published on the digital media website Buckrail. I will refrain from linking to that article here because the piece bouys a dangerous theory, one that could cost people’s lives.

In the story, a local physician posits that given Jackson Hole is a global tourist destination, COVID-19 could have infected scores of people here months ago and hence, we could be approaching herd immunity. He then pointed to antibody testing, which he is offering at his clinic, as a potential panacea for getting people back to work and reigniting the economy.

The article did not provide any viewpoints to challenge these unsubstantiated claims.

Immunity Unknown

First, it’s important to understand herd immunity, a term casually thrown around in the Buckrail piece.

“If a large group of people—the herd—is immune to a virus, then an individual in the middle of this group is unlikely to become infected. The virus has a very hard time getting through the herd,” wrote Dr. Eduardo Sanchez, the chief medical officer for prevention at the American Heart Association and former Texas state health commissioner.

Sanchez, who worked on the SARS outbreak, explained that herd immunity occurs when people in a community are protected from a virus “to a degree that people who are not immune” are also protected. But given how little we know about the new coronavirus, health experts like Sanchez are reluctant to speculate on what it will take to reach herd immunity.

“Herd immunity is disease-specific and is influenced by the ease with which the disease spreads from person-to-person, or the level of contagiousness. The specifics about coronavirus and herd immunity are not yet characterized.”

Achieving herd immunity with the current COVID infection rate will be anything but swift, Sanchez wrote. “The repeated process of infection of one person, recovery, and immunity will take a long time—many, many months or even years.”

Another unknown is individual immunity. Some say the key to knowing that is nascent antibody testing—which shows if a person has been exposed to the new coronavirus according to their immune system’s production of antibodies.

But most health experts are proceeding with caution.

One of the scientists who discovered HIV and went on to develop the first antibody test for the virus, Dr. Robert Gallo, told NBC News: “Some people will say the tests can do more. They’ll say, ‘well, the antibody test also means you can go back to work.’”

That may be true, Gallo said, but he cautioned that the antibodies fail to offer the full picture.

“We can’t tell if the antibodies are protective. There are some suggestions that when you have antibodies, you’re associated with clearing the virus when the antibody titers are good. [A titer is a measurement of antibody levels in a person’s blood.] But that’s not always the case. Sometimes the antibodies are positive and the person is still very infectious.”

Local health officials also caution against placing too much stock in antibody testing. For one thing, “it is unclear whether having the new coronavirus once means you won’t get it again,” said Dr. Travis Riddell, Teton District health officer. “There have been some sporadic reports of reinfection coming out of China, those seem to be rare but we don’t have specific numbers.”

Riddell sits on a new panel of physicians and health officials focused on assessing antibody tests (the FDA has only approved one such kind). Dr. Paul Beaupre, CEO of St. John’s Health, assembled the panel after the hospital decided to pause its antibody testing of health care workers and first responders.

“Until there is a reliable antibody test, we feel strongly that we should continue first and foremost to direct available financial and human resources into doing more widespread COVID-19 active disease testing so that we can more quickly stop the spread of COVID-19 in our community,” Riddell, Beaupre and Jodie Pond of Teton County Health Department said in a joint statement.

A Disclaimer too Late

After the Buckrail story was published, a disclaimer was added to the top of the piece. It reads, in part: “This is a theory presented by one source and in no way implicates [sic] that any of the CDC warnings and procedures should be ignored.”

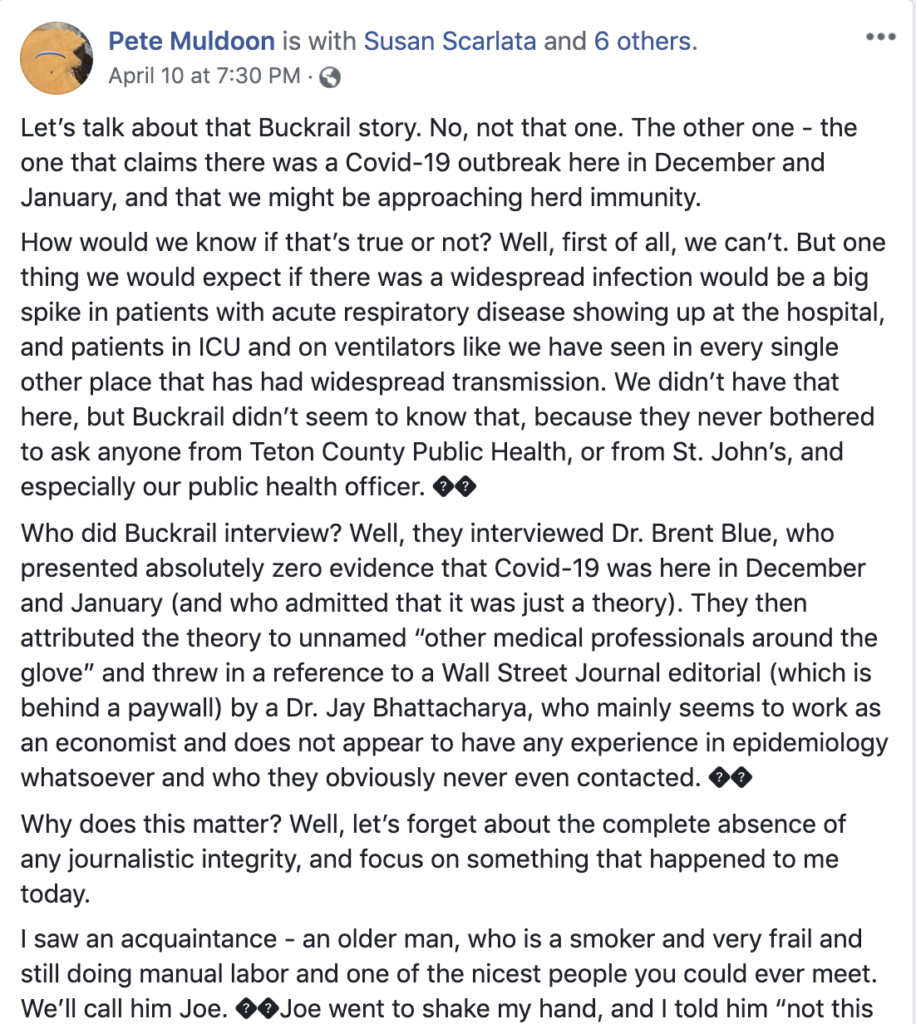

The disclaimer wasn’t enough for Mayor Pete Muldoon.

On Friday night, the mayor took to Facebook demanding the story be retracted and that Buckrail issue an apology to readers. (Buckrail has since published a story refuting its original post.) He referenced “Joe”—a man at high-risk for developing severe illness from the new coronavirus. Joe tried to shake Muldoon’s hand saying he thought he already contracted the virus months ago and was therefore immune. He came to this conclusion after reading the Buckrail article, Muldoon wrote.

“He’s extremely vulnerable, but he’s not practicing social distancing. He’s not wearing a mask. He’s shaking hands. He’s mixing with other vulnerable people. And it’s not his fault—he wants to believe that he isn’t in danger, and he found a Buckrail article that helped him believe that.”

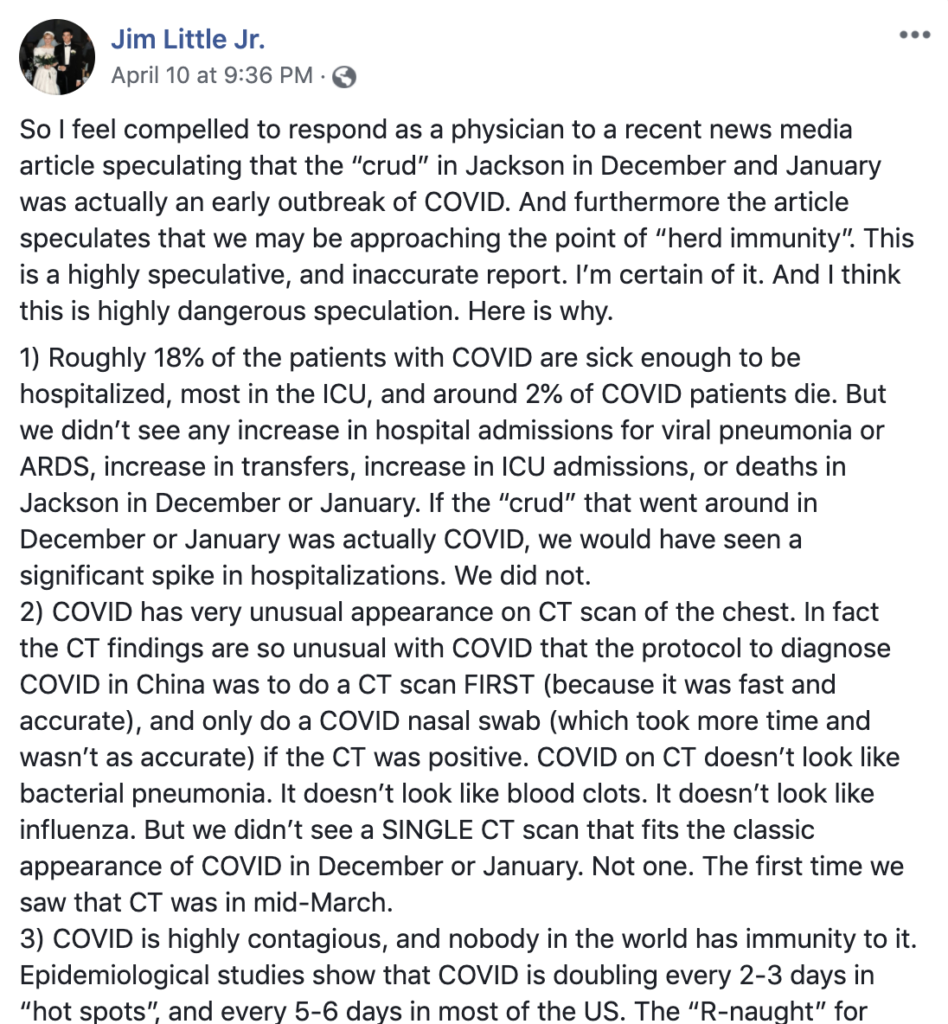

Dr. Jim Little Jr. was also disturbed by the story. The St. John’s Family Health and Urgent Care provider posted on Facebook the same evening as Muldoon. “This is a highly speculative, inaccurate report. I’m certain of it. And I think this is highly dangerous speculation,” he wrote.

Little explained that, had the illness been here months ago there would have been telltale signs. “Roughly 18% of the patients with COVID are sick enough to be hospitalized, most in the ICU, and around 2% of COVID patients die.”

In December and January, Little said there was no increase in hospital admissions for viral pneumonia or ARDS [acute respiratory distress syndrome], transfers, ICU admissions, or deaths.

Wyoming is still potentially weeks away from its epidemic peak, according to a projection by the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. But local hospitalization numbers already line up with Little’s statistics.

In Teton County, 10 patients, or roughly 18% of COVID-19 cases, have been hospitalized. Six have been transferred to ICU. (At first blush, it appears our hospitalization numbers are markedly higher. St. John’s Health lists 36 patients hospitalized due to COVID-related illness. That would be roughly 63% of Teton County’s 57 confirmed cases. But that number also takes into account people admitted to St. John’s for COVID-related symptoms who ultimately tested negative for the virus, Karen Connelly, of St. John’s Health, told me.)

Little also pointed out how diagnostic efforts for the new coronavirus contrast anything providers have seen in the past.

“COVID has [a] very unusual appearance on CT scans of the chest,” he wrote. “In fact, the CT findings are so unusual with COVID that the protocol to diagnose COVID in China was to do a CT scan first (because it was fast and accurate), and only do a COVID nasal swab (which took more time and wasn’t as accurate) if the CT was positive.”

In December and January, his clinic did not see “a single CT scan” that fit the classic appearance of COVID-19. “The first time we saw that CT was in mid-March.”

The Buckrail article asserting “that awful crud” you had a few months ago could be COVID-19 failed to consider another important factor—that Teton County experienced a substantial influenza outbreak during this year’s flu season, particularly influenza B. This year’s flu vaccine didn’t provide protection from that strain, Dr. Paul Beaupre, CEO of St. John’s Health, said in March.

Meanwhile, Little told me his clinic tested more than 200 patients for influenza in December and January. He said the vast majority came back positive.

“When you’re climbing a mountain, you can’t always see the top of it. And getting a view of that summit is something that everybody wants, me no more than anyone else. It’s just sometimes hard to get that view.”

As Wyoming slowly climbs its epidemic peak, people are indeed growing antsy. The Buckrail article, then, offered the view of a smaller mountain, an easier summit.

But it’s important to remember—we’re still in the foggy meadows.

The University of Washington IHME’s latest projection says the state won’t see its highest number of daily deaths (two per day) until May 7. When the model was published last week, it projected a peak at the end of April. The new projection suggests social distancing measures could be helping to slow the spread of COVID-19. But stretching out infection rates, or flattening the curve, requires patience—it means spending more time at home and continuing to limit our contact with others.

It is also worth noting—the model is based on Wyoming enacting a statewide shelter-in-place measure. Gov. Mark Gordon has yet to do that.

Public health officer Riddell says the model signals some of what he and other public health officials are seeing on the ground—that Wyoming is behind the national curve and our bleakest days are yet to come. But he says it should be taken with a grain of salt.

“When you’re climbing a mountain, you can’t always see the top of it. And getting a view of that summit is something that everybody wants, me no more than anyone else. It’s just sometimes hard to get that view and even with computer models, we don’t know if that view is real.”

In the meantime, public health officials like Riddell urge people to continue social distancing, to behave as though they have COVID-19 and could infect others, so that Teton County (population 23,464; home to Jackson Hole) doesn’t find itself in a similar situation to Blaine County (population 23,021; home to Sun Valley).

Blaine County’s per capita infection rate, 1,989 per 100,000 residents, is higher than New York City’s. And its 458 cases have overwhelmed the area’s limited medical infrastructure. Meanwhile, Teton County, with the highest per capita infection rate in the state, 242 cases per 100,000 people, has the rare luxury of learning from its Idaho neighbors during a time when much else remains unknown.

Back in January (which feels like a decade ago), Teton Media Works, publisher of the valley’s venerable newspaper the Jackson Hole News&Guide, bought Buckrail. Publisher Kevin Olson told me Buckrail would maintain its voice and independence, alleviating public concerns that the News&Guide was perhaps eliminating some of its competition with the purchase.

But if that voice and independence could cost people’s lives, it is time to step in and minimize harm.

[An earlier version of this story stated that a disclaimer was added to the Buckrail article after a couple of days. It was added the day after the story was published. -Ed]