Lynne Huskinson put 39 years into the coal industry, working faithfully as an operator for a mining company near Gillette. That is, until spring 2019, when her employer—Blackjewel—filed for bankruptcy. Huskinson and 600 other employees were told they had been laid off.

Lynne Huskinson recently ran for office as a Democrat in Wyoming’s 32nd House District. She is now promoting a “just transition” to renewable energy (Courtesy Photo).

“My life changed because I thought we’d be back to work in a week or so,” she said. “It didn’t happen, so, I ended up filing for unemployment. I hadn’t filed for unemployment or even worked with job services since probably 1978.”

Although many of her friends found work at other mines, Huskinson was ready to move on. Coal, she claims, is permanently on the downturn, despite what many of her former coworkers believe.

“People just think it’s going to come back because we have so much of it,” she said. “It’s just not…It’s not a sustainable commodity. People don’t want it.”

Coal production in Wyoming has dropped by about a third this past year. And just last month, the state’s second-largest coal company announced plans to shutter two large mines. That includes the Black Thunder mine—the second-most productive mine in the nation and an employer of over 1,000 people. University of Wyoming economist Rob Godby said coal’s decline has major economic ramifications for the state’s budget, as well as for the wellbeing of its residents.

“Direct oil, gas, and coal production accounts for about six percent of employment in the state, but it’s over 50 percent of our revenues,” Godby said. “And so it’s a disproportionately large part of our revenue stream.”

Wyoming accounts for about 40 percent of all coal mined in the U.S., and produces 15 times more energy than it consumes. It exports its natural resources in massive amounts to states like California and Oregon, and thus has miles of power transmission lines already in use, connecting it to the western grid. National utility companies pay Wyoming taxes to use its coal power. But now, that money stream is drying up as other states look for cleaner energy. Natural gas and oil are down this year, too.

“That’s really what’s caused so many problems with respect to revenues, because we depend so heavily on all three commodities,” Godby said.

New Opportunities for An Energy Boom

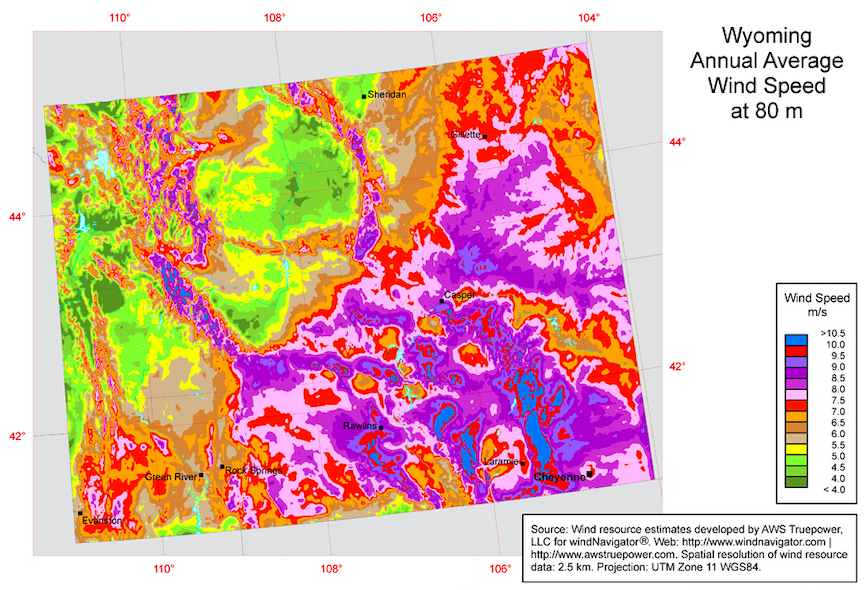

Wyoming is now scrambling for revenue and jobs solutions as the nation looks to transition away from fossil fuels. But one possibility remains in the power sector. Wyoming’s high prairies and violent, gusty plains give it some of the best potential for harnessing wind in the West. Plus, the aforementioned transmission infrastructure already exists, often automatically connecting wind turbines to the western grid.

A map of Wyoming’s wind resources. Blue, red, and purple represent high wind speeds, and thus excellent potential for energy farming. (Screenshot).

And developers have been jumping at this opportunity recently. The state has more than double its current wind capacity under construction, and Godby thinks that can be profitable for the state, though not a replacement for coal. Wind companies currently pay three state taxes: sales, property, and generation (one dollar for every megawatt-hour of power produced).

“You do get an ongoing tax stream and it’s not insignificant,” he said. “And if you look at taxes in the state of Wyoming this year, where they’re down almost everywhere because of COVID, they’re through the roof in Carbon County primarily because of these new wind projects.”

While 15 out of 23 counties in Wyoming lost tax revenues—in some cases by more than 50 percent—in 2020’s second quarter, Carbon County experienced growth of over 108 percent. This demonstrates wind’s potential as a tax generator in an era where Wyoming is in a desperate situation with its state budget. Even after cuts to government services across the board earlier this year, the state is still facing a deficit of nearly a quarter of a billion dollars. Wind, like fossil fuels, is a net positive revenue source for Wyoming.

“Basically, wind does cover its cost of additional public services if it attracts people to the state,” Godby said. “It’s the only other sector that does.”

And revenue is not the only benefit of wind turbines. They provide good-paying jobs, especially as they’re being constructed, and capital for small businesses. Tom Darin, Director of Western State Affairs for the American Wind Energy Association, believes winds can become Wyoming’s next great export to other states, just like coal.

“Coming out of COVID in particular, we see a big opportunity for this state to diversify its economy,” he said.

A Tax Debate as Timeless as Wyoming’s Wind

But some Wyomingites say wind developers aren’t yet contributing their fair share to the state. Lawmakers are considering raising current generation taxes, which could help close budget deficits. And just last week, Wyoming lawmakers—by a narrow seven to six margin—approved a bill to repeal the current three-year tax exemption on electricity generation that applies to any new wind projects. The bill will be up for review this legislative session.

A recent screenshot of the Wyoming State Joint Revenue Committee, which includes State Sen. Cale Case (middle-right top). Tom Darin (bottom middle) advocated against new taxes for wind developers at the August meeting (Screenshot).

This bill would make it more expensive to build in Wyoming. And Tom Darin believes the state could actually miss out on potential revenue because of that. Pennies can decide if a wind developer builds in Wyoming or chooses another location out West. And revenues are only generated if a company actually builds their farm.

“A small change, an uptick, can really knock you out of being competitive,” Darin said. “And we’re not opposed to taxes. We just want to keep them at a reasonably competitive rate. And we think the three that we have in the state fit that balance, but raising them will probably make us uncompetitive.”

Wyoming’s neighbors are also looking to capitalize on a wind rush; competition is high. If you were to build a wind farm in New Mexico, you would actually receive a tax credit for producing power. Plus, there’s financial relief from property taxes and equipment sales. In short, its government really encourages development. That’s why a 2019 study by Rob Godby at the University of Wyoming ranks New Mexico first in the West in terms of the cost and value for potential wind developers. Wyoming ranks fourth.

Unlike the world-renowned coal deposits in The Powder River Basin, which dominate the industry, Wyoming’s hold on the wind industry is low. Cost and technology can render many advantages Wyoming may naturally have obsolete, which may lead developers to choose other wind plains.

“That’s the misconception, is that everyone needs Wyoming’s wind,” Darin said. “And that’s just not the case.”

Of course, companies are still investing in Wyoming in large numbers and building acres of wind farms. And that’s in part because taxes haven’t been raised yet. But the current wind rush does come at a cost, according to State Senator Cale Case, a Republican lawmaker based in Lander.

“I argue that we are severing something from future generations as well. These magnificent vistas,” he said. “My grandchildren will never see the Wyoming that I was able to look at. And so they lose something. They’re not at this table to negotiate the compensation, so I have to do it for them.”

Case sees the value in wind energy, but he also claims the state needs “fair compensation” for the power they’re providing for the rest of the West. He compares California and Oregon’s use of Southeastern Wyoming’s landscape to colonialism, saying residents in many other parts of the county wouldn’t ever allow turbines to be placed in their backyard.

“If you had great resources in Teton County like the South Pass produces in that giant funnel in Southeastern Wyoming, would you be installing turbines all through the valley? I don’t think you would,” Case said. “So, the question is, what about the rest of the state? And here’s a confession that I have. My favorite places in Wyoming, it’s not Teton County…I love it there, but my very favorite places to be are these wide-open spaces that are largely untouched…That’s important to me. So I only make this point so that the people that value Teton County—and wouldn’t dream of thinking that was a good place to put a whole bunch of wind turbines—understand some of our perspectives about something that’s very dear to us.”

The wide-open spaces of Wyoming (Wayne Broussard/Shutterstock).

Case argues that if he causes the wind industry to hesitate, “just for a second,” and pay a bit more to compensate his constituents, that’s not a horrible thing. And he argues that his colleagues need to remember that wind impacts are long-term.

“There’s a lot of desperate people in Wyoming,” he said. They’re afraid. Boom and bust economy. We’re in a bust, and it looks to deepen. So they see the benefits of wind development. But the trouble is, those are very fleeting and short and upfront.”

University of Wyoming’s Rob Godby predicts that developers could potentially afford modest tax increases, but that lawmakers must tread carefully. Any hesitation, just for a second, can crush Wyoming’s chances to capitalize on wind.

“If we tax it too heavily, we could kind of kill the potential goose that could lay the golden egg,” Godby said. “And right now, we’re looking for any golden eggs we can find as we try to diversify our state economy away from fossil fuels.”

Godby also asserts that discussions about raising taxes, which have happened nearly every year for the past decade, need to stop. There’s no telling how many wind companies have chosen to place their farms elsewhere already; however, uncertainty is never good for an industry making long-term decisions.

The Impacts of a Wind Boom on Everyday Wyomingites

Lawmakers aren’t the only ones who might appreciate some checks on wind energy, though. Paul Montoya leads a citizen coalition for smart energy development in Albany County. He argues that wind farms cause noise pollution, disrupt animal migration, and depreciate property values. And he’s not alone. More than 2,700 people signed a petition Montoya launched urging regulatory action against prospective industrial sites near Laramie. And just last week, Wyoming lawmakers denied a grant for a potential land lease for the proposed Rail Tie project, which Montoya vehemently opposes.

“I think it was a case where a lot of people thought, well, this is a bunch of residents that don’t want something in their backyard,” Montoya said. “And where it’s really gained traction is that people have realized that, well, it might not be in my backyard, but it is where I play. And when my visitors drive into town, it’s the first thing they see.”

Montoya has several videos of already-built industrial facilities outside Cheyenne, and they are indeed imposing. They show the droning of turning engines and blades on top of towers nearly 500 feet high. And dozens of red blinking lights—in place to ward off aviation—dot the night sky. Cars, houses, and even rolling hills are dwarfed by these turbines.

Footage of the Roundhouse Wind Energy Project, located about 9 miles west of Cheyenne (Courtesy of Paul Montoya).

It’s easy to see why a person might find this a permanent scar on their landscape. But coal mines—gigantic pits carved out of buttes and plains—are scars, too. Lynne Huskinson, the former coal miner, is now an advocate for a just transition to renewable energy.

A coal mine in the Powder River Basin. As land is removed for coal extraction, nearby waterways and airflows can be contaminated. Mining also destroys wildlife habitats and disrupts aesthetic elements of landscapes. (Jim Parkin/Shutterstock)

“I’m just trying to be a thorn in the coal industry side right now, because, dang it, I was a good operator, and I had a really good life working in coal,” she said. “But I wish I would have paid better attention to what’s happening to our climate.”

Discussions around this topic are likely to continue for as long as Wyoming’s wind keeps blowing.

This story is part of a collective series with the Rocky Mountain Community Radio collective about fossil fuel usage in the West. Stay tuned for more stories like this one from other reporters from across the region.