This story is part of a Rocky Mountain Community Radio collaboration on fossil fuel transitions in the West.

For nearly a century, Colorado’s North Fork Valley relied on coal for high-paying jobs and a thriving economy. But as the mines close their doors, they leave behind a troubling legacy: leaking methane.

Eric Edwards maneuvered his machine through sandy sediment in the mudflats on the Paonia Reservoir. He was hired by Delta Brick and Climate Company to collect 40 cubic yards, about four dump truckloads, of sediment from the reservoir.

In 2017, Chris Caskey founded Delta Brick and Climate Company, which manufactures tile and brick. The company also operates with a mission: to find solutions to environmental problems in the North Fork Valley while creating jobs in a transitioning economy.

The first problem Delta Brick tackled was the excess sediment in Paonia Reservoir. The sediment creates a high-quality clay they now use to make tile and brick.

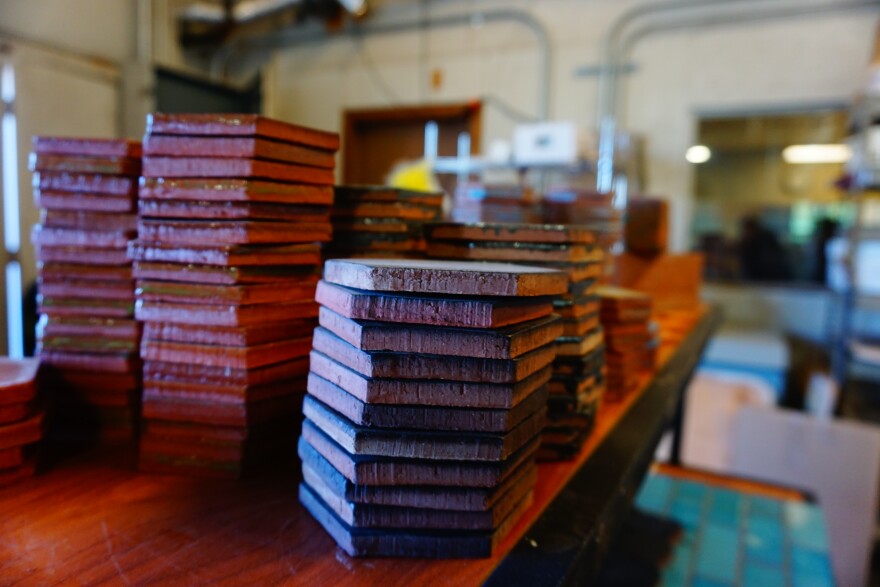

Stacked coasters made from Paonia Reservoir sediment at the Delta Brick factory in Montrose. (Stephanie Maltarich/KVNF)

“All of the water that is stored is committed to go to farms downstream from here in the Paonia and Hotchkiss area. So, this mud and sediment that has filled in, has made about a third of that storage capacity go away, and so their irrigation season has shortened,” Caskey said.

Then, Caskey brainstormed solutions to manage the methane that leaks from abandoned coal mines in the area. A 2016 study by Colorado’s Energy Office found that nearly 20 abandoned coal mines in and around the North Fork Valley have the highest potential for methane capture than any other former mines in the state.

“So, the coal mines are leaky. They leak all over the mountainside, primarily from old mine shafts and portals but also cracks in geology. We would like to start using the sediment in the reservoir to seal off these leaks,” Caskey said.

After a couple of years of research and conversations with stakeholder groups, Caskey, who is also a chemist, has found a way to address both problems with one solution: he wants to seal the leaking mines with plugs manufactured with sediment.

“That will make our methane capture systems more efficient [and] keep more methane out of the atmosphere,” he said. “And essentially eliminate methane leaking from the mines, keeping in line with new global standards.”

A few days after it was collected, a dump truck full of sediment arrived at Delta Brick’s factory, located in a large, airy warehouse near downtown Montrose.

Two employees manage the factory’s day-to-day operations: from mixing clay, firing kilns and glazing tile. Evan Barrett is the production manager, and he said he appreciates working for a company with a business model focused on solutions.

“It’s a creative idea just in the way it is really trying to make the maximum impact from all different angles. Not just the watershed issues and water storage, not just methane, but also creating jobs in coal communities,” Barrett said.

Delta Brick has seen steady growth in brick and tile sales over the past year. But Caskey said grants from various state agencies have been essential to keeping the business running. He commends Colorado’s leadership in supporting communities in transition.

“Colorado has been great, and it’s the first in the nation to have actual resources and humans thinking about how to make this transition good for other people and good for communities,” Caskey said.

Wade Buchanan, the director of the Office of Just Transition, created by the state in 2019, said he is inspired by creative solutions like Delta Brick because it’s important for individuals and communities to decide what they want to do moving forward.

“If we came into a situation and said, ‘Okay, you guys are mine workers who are being displaced. Here are three kinds of jobs you can have, and we’re gonna work with you on those three kinds of jobs,’ it would have limited their future, and would have limited the community’s future,” Buchanan said.

Caskey said he agrees it’s not about telling people what to do. It’s about an appropriate response.

“The correct relationship to this reservoir is to take the mud out that comes in. The correct relationship with these abandoned coal mines is not to totally abandon them, but capture methane and get it out of the atmosphere,” he said.

Caskey said Delta Bricks’s next step is to move the factory to an abandoned coal mine in Somerset, where they will use captured methane to power brick and tile operations.