Luke Zender made just a dozen signs—he wasn’t sure many people would come.

Zender created a Facebook event for a Black Lives Matter protest on May 30. Just 24 hours later, while he kneeled with his masked face bowed toward the ground, his gloved hands holding a sign that read “Black lives matter,” roughly 150 people peacefully gathered on Jackson’s town square.

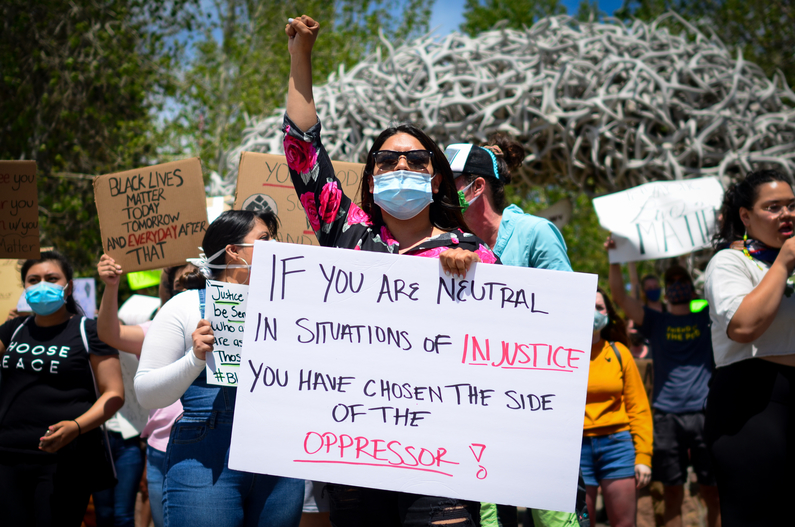

For three hours they chanted, kneeled and brandished signs quoting civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. — “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Words from Desmond Tutu, the South African archbishop that fought against apartheid, appeared on several others: “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.” Some signs urged white people to take action and become better allies to people of color: “White silence equals violence.”

Jacksonites also referenced George Floyd’s last words: “I can’t breathe.” The haunting sound of protesters chanting that phrase, among others, filled the town square Sunday afternoon.

Roughly 150 people gathered on Jackson’s town square Sunday, May 31 for a Black Lives Matter rally. The large crowd suggests Jackson is having a moment of reckoning. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

Protests like this one were sparked by the killing of Floyd, an unarmed Black man who died on May 25 at the hands of police after a white Minnesota police officer kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes.

Floyd’s death was captured in a video that went viral and prompted the Minneapolis Police Department to fire the four police officers involved. The officer that pinned Floyd to the ground with his knee, Derek Chauvin, was facing third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter charges. On June 3, amid persistent civil unrest, prosecutors raised the charge to second-degree murder and charged the other officers involved with aiding and abetting murder.

Nationwide, people have been protesting Floyd’s death, police brutality, and systemic racism for the last week and a half, resulting in clashes between police and protesters that America has not witnessed since the 1960s. On Monday, President Donald Trump stunned many Americans when he threatened protesters with martial law.

The protest in Jackson, meanwhile, contrasted the chaos in other parts of the country.

Police played a passive role. Officers kept their distance from peaceful protesters, avoiding the southwest corner of town square where most people congregated, a move that strayed from local policing efforts during other demonstrations. Oftentimes during rallies, officers walk the perimeter of town square and sometimes interact with demonstrators. (Read Chief of Police Todd Smith’s reaction to Floyd’s killing.)

Fueling the solidarity, dozens of drivers on Cache honked and raised their fists in support of protesters. Briana and Jorge Olivares took their hand-painted “Black lives matter” banner, affixed it to the outside of their black pickup truck and circled the square, honking and pumping their fists.

In between, there were a few tense moments.

Some motorists drove by shouting, “All lives matter!” Others revved their engines to cloud protesters with exhaust. Across the street, a white 60-something man yelled expletives. “Look at ‘em, arrest them! Hey, film this, Fox News! These people aren’t even from Jackson County,” he shouted, apparently referring to Teton County. The man also threatened the media. “Come any closer and I’ll knock you out!” he said.

One brave protester was undeterred. She went on a peacemaking mission and crossed the street to engage the man.

Contrary to the man’s grumblings, most protesters were locals. And this was not exactly the first Black Lives Matter demonstration in Jackson. Four years ago, when four African American men—Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Terence Crutcher, and Keith Lamont Scott—were killed in succession by police, activist Sarah Ross held 12 weekly vigils in the town square. But her efforts amassed paltry support. In 2018, I asked her to discuss this in a column for Planet Jackson Hole when I was editor of that paper.

“These vigils did little but to help me see how unprepared I and many of the white people in Jackson are to talk about race, let alone to protest, to mourn, to effect change,” she wrote. “Locals and tourists alike asked me why I was holding vigils in Jackson and impeding the view of the town square. ‘It’s nice that you care,’ was a common response, ‘but it doesn’t really impact us. What we do here doesn’t really matter.’”

Sunday marked a pronounced change for residents. That day, and the days before and after, when Black Lives Matter protests have transpired not just in big cities but also small towns across the country, suggests a growing number of people in places like Jackson are ready to engage in difficult conversations about structural racism in America—”an awakening,” as some activists on Sunday put it.

Zender co-organized the event, along with Courtney Roberts, Doug Miller, and Tina Rene Seay, because he feels a responsibility. As a white man, he wants to do everything he can to dismantle “systems of oppression,” he said.

Luke Zender, right, co-organized a Black Lives Matter rally Sunday in Jackson. He said he had to use his privilege as a white man to honor George Floyd’s life and protest his killing. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

He hoped the protest would engender “awareness, knowledge, wisdom and truth” about the systemic racism people of color face in America and the frequency with which unarmed black people are killed by police.

Research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows police use of force is a leading cause of death for Black men. They are roughly 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police than white men. “This study shows us that police killings are deeply systematic, with race, gender and age patterning this excess cause of death,” said study co-author Michael Esposito, a postdoctoral researcher in the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research.

Seeking Unity, Justice

Whether it’s protesting climate change, decrying or supporting the president, white folks often comprise the majority of protesters that take to Jackson’s town square. But this demonstration was different. White, Black and brown people, including dozens from the Latinx community, joined together on Sunday. Families and older folks were among the crowd but many were teenagers and 20-somethings.

Keaton Chamberlain, 13, and her two friends were some of the first to arrive at town square. The Jackson Hole Middle School students had never attended a protest before but said they simply couldn’t stay silent this time around.

Chamberlain, who is white, said she and her friends have “taken it really hard and we can’t imagine how hard the Black community has taken it, so we just want to help support them and let them know that we’re here for them.”

She is watching national protests, some that have turned violent, through a lens of understanding. “They said ‘no justice, no peace,’” she said of the protesters, “and that’s what they’re doing, so I support them.”

Shari Brownfield, of Yemini and caucasian New Zealander descent, brought her 13-year-old daughter Finley to the protest. Since Floyd’s death, the mother and daughter have had several discussions about police brutality and systemic racism. They learned about the demonstration “just a few minutes” before it began and headed to the square.

Brownfield said she doesn’t promote or condone the violence that has swept through some protests throughout the country. “But at the same time, I just wish people would be as upset about the lynching and killing of Black people as they are about looting and burning of buildings and the things that are happening in the street,” she said. “There were times when people tried to protest peacefully, like taking a knee, and people complained it was interrupting their football games. So I can see the hopelessness that creates and why this is happening.”

“I just wish people would be as upset about the lynching and killing of black people as they are about looting and burning of buildings and the things that are happening in the street.”

Cinthya Benavides, a Latinx resident, was protesting for her “Black brothers and sisters.” Police brutality, she said, has gone too far.

Benavides shied away from using the word “riots” when referring to national demonstrations that have turned violent. “I consider them rebellions,” she said.

Some activists have long described the racially charged unrest that swept the country in the 1960s as a “rebellion” or “uprising.” The terms are meant to convey the systemic oppression that spurred people to action, however violent. Take the historic burning and looting in Detroit circa 1967. “To use the contested language of the 1960s, Black Detroiters engaged in an uprising against a racially unequal status quo, a rebellion against brutal police and exploitative shopkeepers,” wrote Thomas J. Sugrue in “Detroit 1967.” The book draws parallels between the civil unrest of the 1960s and the racial tension of today largely sparked by police killings of unarmed Black people. “Many of the causes of the long, hot summers of the 1960s remain unaddressed,” Sugrue wrote.

When people have tried to address those causes peacefully it has resulted in little change, Benavides said. She also pointed to former NFL player Colin Kaepernick who peacefully protested police brutality and racial injustice by kneeling during the national anthem at football games. “Everybody had a problem with that. I believe that this is the way they are getting people’s attention,” she said.

Vince Wisniewski, holding a sign appealing to fellow white people: “Don’t let tears be your only reaction,” agreed. He said watching images of people protesting and rioting throughout the country made him feel “energized, to say the least.”

“Our history is founded on riots, our history is founded on forced change,” Wisniewski said.

Still, he acknowledged the thick fog of uncertainty looming over America, that the civil unrest from coast to coast could result in several different outcomes. “We clearly have a president who is willing to use the things that we pay for—police, the military—to suppress voices.”

Wisniewski said Trump could “easily” be a force of unity and help to deescalate the situation, but he is not doing that. In addition to what mayors, governors and Trump’s former defense secretary James Mattis have called Trump’s use of divisive language during a time of deep racial tension, the president also ordered on Monday for peaceful demonstrators to be sprayed with tear gas near the White House so he could pose in front of St. John’s Church with a Bible.

Maleah Tuttle has been watching this all play out with concern and skepticism. “Citizens are beginning to see that the government doesn’t have our best interest in mind and we have to take accountability,” she said.

Tuttle led the crowd in chants that day, her hoarse voice shouting: “Hands up!”

“Don’t shoot!” the crowd responded.

Maleah Tuttle has become a fixture at social justice-centered rallies. The high school senior led the crowd in chants at a Black Lives Matter protest Sunday. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

A high school senior, Tuttle has become a fixture at local protests centered on social justice issues. Lakota Sioux, Flathead and Umatilla, she often drives the conversation toward America’s treatment of Black and brown Americans. Sunday was no different.

“We are a country built upon systemic oppression and until we begin to push back against that, it will not change,” she said.

Tuttle said the death of Floyd could be “an awakening” for Americans. She hopes it compels people, even those who can’t come out to protests, to action. She urged folks to call their representatives, to have difficult conversations with friends and family about what it’s like to be a person of color living in America, to donate to the families of those killed by police and to organizations fighting for racial justice.

Rosa Sanchez shared duties with Tuttle, steering chants and engaging the crowd. She echoed her protesting counterpart—that these demonstrations could catalyze a widespread reckoning. “Once we build a culture of education, of people knowing what is happening around them, then I believe we can start a conversation towards solutions,” she said. “But until people recognize there is a problem, we can’t.”

“Once we build a culture of education, of people knowing what is happening around them, then I believe we can start a conversation towards solutions. But until people recognize there is a problem, we can’t.”

Sanchez feels empowered watching the waves of nationwide protests. “But it also makes me feel concerned that it had to rise to this level for people to start paying attention,” she said. “If these conversations would have started years back, I don’t think we would have ever gotten to this point.”

An immigrant, Sanchez was born in Mexico and grew up in Jackson. She says she was encouraged by the diverse composition of Sunday’s crowd. It represented a vision of America she has always believed in.

Rosa Sanchez joined Maleah Tuttle, mobilzing the crowd on Sunday with chants “No justice, no peace” and “I can’t breathe” — some of George Floyd’s last words. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

Sanchez came to the U.S. when she was seven years old, is a DACA recipient and college graduate. Today she works as an advocate at the Community Safety Network to give back to a community that has supported her. But while she has not personally experienced racism in Jackson Hole, she knows it exists and wants to support Latinx people, Black people, “and anyone else experiencing racism.”

The protest precipitated dialogue about the lived experiences of people of color in Jackson Hole, a place many caucasian folks have deemed “a white town,” but with a population of Latinx people that community advocates say is around 30 percent. (U.S. Census estimates say 15 percent.)

Meanwhile, African Americans living in Jackson comprise a significantly smaller portion of the citizenry, at least according to government numbers. U.S. Census estimates say Black people make up less than 1 percent of the county’s population.

Emilé Newman, an African American, held a sign that read, “Ignorance allied with power is the most ferocious enemy of justice.” She attended the protest “to speak for those who can no longer speak for themselves.”

She says she has a complex relationship with her town that has recently come into sharper focus. While Black and brown Americans are reeling, she said it is difficult to feel disconnected from people of color, to miss out on that solidarity she would feel in a place with a larger Black community.“But this is where I am, and this is where I can speak up and have a voice. I have mixed feelings about it,” she said.

Newman urged white people to acknowledge how long people of color “have been carrying this torch,” fighting for racial justice.

Emilé Newman, right, says the endless battle over racial injustice is exhausting. “But there is no time to be tired while people are losing their lives.” (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

Sunday’s protest later reflected more of the frustration and emotional labor people of color endlessly face. Toward the end of the three-hour demonstration, an African American woman, who identified herself only as Rosie, began to shout from the window of her navy Subaru. Most folks couldn’t hear so the Denver resident pulled around and got out of her car.

As protesters chanted “No peace, no justice,” Rosie stood on the street addressing people. “If you don’t know what we need to change to make change, why are you here?” she said. She referenced a Slate article and told them that unless they educate themselves about “qualified immunity,” their actions were “pointless.”

Several Jacksonites approached Rosie and asked her to send them the article and this perked the ears of Rep. Mike Yin-D, Jackson. Yin, Wyoming’s first Chinese American state lawmaker, often participates in local protests.

“I can literally change the law so I would like to know,” Yin told Rosie.

Rosie was referring to the Civil Rights Act of 1871. Under Section 1983, people can sue for civil rights violations such as excessive police force. The Slate article explains, however, that under the Supreme Court’s current interpretation of Section 1983, victims are rarely successful seeking justice. Provisions to the act have “transformed Section 1983 into a rubber stamp for egregious police misconduct.” The article cites several examples.

“I’m tired,” Rosie told KHOL. “What are we doing? Are we kneeling, are we shooting, are we setting police headquarters on fire? Nothing is working.”

“I’m tired. What are we doing? Are we kneeling, are we shooting, are we setting police headquarters on fire? Nothing is working.”

While there is “some truth to righteous anger,” Rosie said, she condemned the civil unrest unfolding across the nation. “We can protest, we can make our voices heard, but when you’re destroying property, we don’t really have the goal in mind that we should. It makes the conversation about something else.”

A Denver resident who identified herself as Rosie spoke to protesters about problems in the judicial system that prevent victims of police violence from seeking justice. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

Yin, ever the tenacious politician, stepped aside with Rosie to engage her further. “The women’s marches—we did those three years in a row and nothing happened. So the question is, what is the next concrete step? How do you actually make action happen?” he asked.

Rosie suggested abolishing the police and using “small test markets, small towns,” to determine how to hold people accountable without law enforcement before enacting such measures in bigger cities. “The problem with policing is that it is so ingrained in our culture, it has so much staying power that there is no room for questioning,” Rosie said.

Police abolition presents more questions than answers. How do you keep a community safe without law enforcement, critics wonder. Some advocates are calling for other solutions, such as redirecting funds from police departments. That would mean prioritizing government funding for social services over law enforcement and scaling back some police duties. Los Angeles, for one, is cutting $150 million from its police budget and directing that money to “youth jobs, health initiatives and ‘peace centers’ to heal trauma,” the Los Angeles Times reported. As people examine ways to prevent another death like George Floyd’s, these options are spurring dialogue across the nation. Some are also challenging police responsibilities and funding as they see images of law enforcement and protesters violently clash and police target journalists in cities across the country.

For resident Jailyn Wallace, an African American, a peaceful way forward is the only way, but he says that starts with protesters.

He moved to Jackson eight months ago from Ohio to build Habitat for Humanity homes “and fell in love with Jackson.” When he arrived at town square halfway through the protest on Sunday, he walked through the elk antler arches and marveled at what he saw.

As a member of the Black community, he said it was important for him to attend. That the protest was peaceful was also significant, Wallace said. He invoked Martin Luther King Jr., who championed nonviolent resistance in his struggle for racial equality. “The rioting is taking away from the message that we as the Black community are trying to express to other people, which is peaceful protesting that Martin Luther King preached and many other civil rights leaders in the past. It’s taking away from the message that we’re trying to bring. It’s not moving us forward, it’s bringing us backward.”

Wallace said he hoped the protests in Jackson and cities across the nation illuminate the ongoing struggles that, long after King’s time, African Americans continue to endure. “I want everyone to open their eyes and see how we as Black people are treated around America, and see that we are people and that we have the same rights as everyone else.”