With camping chairs and a few picnics in tow, a multigenerational crowd numbering at least a couple hundred people started arriving early for Justin Farrell’s Aug. 3 talk at the Center for Arts’ outdoor amphitheater—all curious to hear more about his research on the ultra-wealthy of Teton County.

“We both grew up here and have lived here our whole lives and we’ve watched the valley at least change from when we were young to now,” said Hannah Wakeman, 23, who came to the talk with her friend Gwen Dowson, 22.

“It’s kind of become pretty unattainable to live here because of the prices of everything. I feel very lucky to be able to come home to my parents’ house and everything but it doesn’t—it’s not looking super hopeful for my own future here.”

Asked whether they think the ultra-wealthy have too much money, Wakeman and Dowson didn’t hesitate.

“Yeah. Nobody needs a billion dollars, guys!” Dowson said, laughing.

“I would agree,” Wakeman added. “A billion dollars is too much money.”

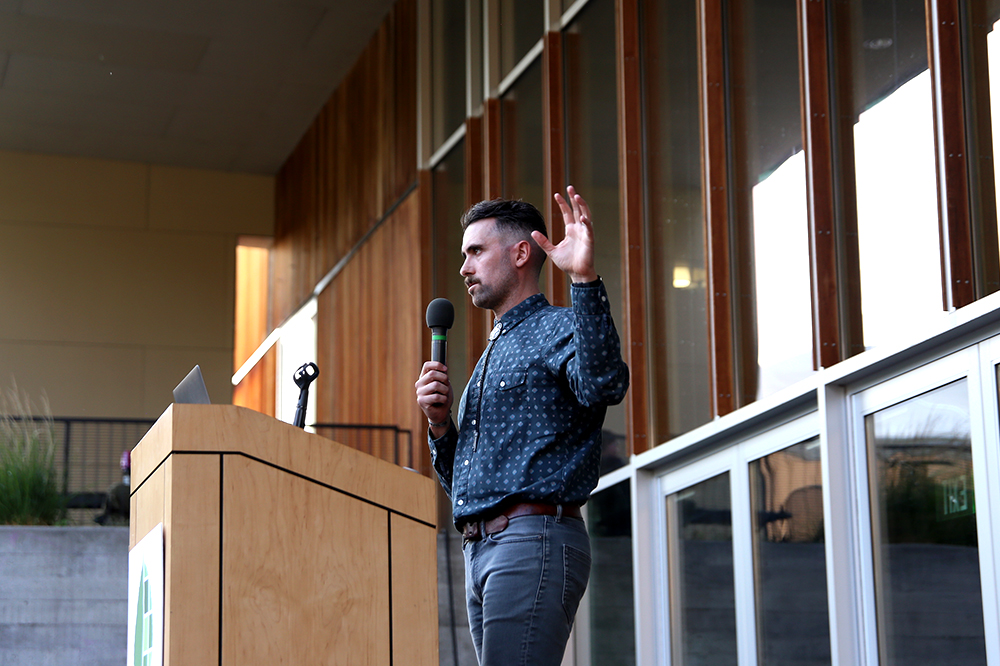

Farrell opened his talk by asking attendees to raise their hands when he asked whether they were tourists, part-time or full-time residents of Teton County. The majority of people in the crowd were full-time residents. (Kyle S. Mackie/KHOL)

Courtney Van der Weyer also grew up in Wyoming but now lives in Cambridge, England. Speaking before Farrell’s talk started, she said there’s always been wealth in Teton County, and for good reason.

“I think there’s a lot to answer for Wyoming income tax, [its] lack of income tax. And that’s why a lot of them [the ultra-wealthy] are here,” Van der Weyer said. “I don’t have a negative attitude towards them because I think most people, a lot of people would do the same. And I think in terms of an impact, they make the cost of living so high that there are certain services that are going to be being lost more and more, and we’ve seen that this summer, some really important services that are going to be lost because the staff just can’t be here.”

“Because of technology and the dotcom stuff, we now have billionaires where we only had multimillionaires [before],” said Larry Morgan, a part-time Jackson resident who built his home in the valley 30 years ago. “But I don’t know that they’re harmful. I don’t know many of them. They don’t bother me.”

Morgan also said that major changes to Jackson Hole have always been inevitable.

“Jackson’s, you know, it’s already gone. It’s been gone for a long time, so people should just get used to it. It’s not going to be a charming little mountain town anymore with, you know, local stores,” he said. “The valley will continue to fill in and the character of Jackson will change.”

As much as some other locals might not want to hear it, Morgan’s take is similar to some of the conclusions that social scientist, Yale University professor and native Wyomingite Justin Farrell came to over the course of researching and writing “Billionaire Wilderness: The Ultra-Wealthy and the Remaking of the American West.”

Copies of “Billionaire Wilderness” were available for sale during Farrell’s talk. (Kyle S. Mackie/KHOL)

KHOL interviewed Farrell ahead of his public talk. The following partial transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity. Listen below for the full conversation between KHOL News Director Kyle Mackie and Farrell or catch it as a bonus episode of our weekly podcast “Jackson Unpacked” on Monday, Aug. 9.

KYLE MACKIE: You do not mince words in “Billionaire Wilderness.” You describe in great detail how the ultra-wealthy use nature to solve economic dilemmas, often benefitting from the positive community feedback of environmental philanthropy, while at the same time further enriching themselves. You describe how they often mistake relationships that are based on economic exchange as genuine friendships. And I’m dying to ask you, what has the reaction been to your book from these ultra-wealthy people who you interviewed and who were generous with their time and who I’m sure you got to know over the course of your five years of research?

JUSTIN FARRELL: I did, yeah. I still have great relationships with some of them. You know, there wasn’t this intense blowback that you might expect. But as a social scientist, I know that that’s probably biased in the sense of those who are upset, you know, may not reach out. But overall, I think that most people, even if they disagree with some of my interpretation of maybe their relationship with someone who works for them or their relationship with their fishing guide or something like that, that I used really good data and that I told the story in a way that was hopefully accurate. And I really went to great lengths to do that, even though, you know, at times, usually with their own quotes, it can be quite critical and even cringe inducing for some people.

Social scientist, Yale University professor and native Wyomingite Justin Farrell speaks at Jackson’s Center for the Arts on Tuesday, Aug. 3. (Kyle S. Mackie/KHOL)

MACKIE: I wanted to just read this quote you have in the book. You say, “People (both wealthy and non-wealthy) and organizations that are genuinely interested in moving beyond the status quo and Band-Aid solutions should focus on using their money and power to reform policy and build more equitable institutions.” So, I wondered if you could talk about some of the policy reforms that you discuss in the book and some kind of maybe practical takeaways that folks might want to grasp on to if they’re feeling depressed about what you have written.

FARRELL: Yeah, so I—at the end of the book I have this epilogue and it was really difficult to write because things are changing so quickly. And so, I shied away actually of recommending specific policies. And a lot of times academics are not very good at that. And so, I have these broad recommendations and it starts with first requiring more from the ultra-wealthy. And that can happen in lots of different ways—through, you know, a tax on luxury real estate transfers. You know, I think last year was like $2.4 billion dollars after COVID in luxury real estate but virtually none of that’s going into the community. At the state level, I talk about Wyoming’s lack of income tax. I talk about lack of a corporate tax. And so, there are some really easy remedies on paper, but the State of Wyoming is not instituting an income tax anytime soon. The local government where I was born in Cheyenne, I mean, it’s gone further and further to the right. Even if it’s you know, we’re talking about taxing people that, to be honest, they don’t like in terms of Jackson and Teton County, they don’t even really consider it Wyoming, yet even still they’re not willing to tax those folks coming from California or Texas or wherever it is that are not like them, don’t really share their values and are coming to benefit financially from this tax shelter that, you know, Wyoming has become. So, I talk about that a little bit in the book.

Then I have, you know, as a sociologist, I’m really interested in studying community and what makes a community. And this is a little more mushy and rather than just saying, you know, ‘institute this policy’ or ‘the town council should do this,’ or ‘here’s how you fix the housing crisis,’ which is [laughs]—let’s not even get into that—but what type of community do you want to be? Who belongs in the community? What gives a community character? And starting at that broad level with those types of questions, that again sounds sort of like, ‘Okay, what’s that going to do?’ And then moving from there with the policy… I don’t think that Jackson has really done that. They have the comp plan [Jackson/Teton County Comprehensive Plan] and everything but there’s not a lot of room or a lot of space, especially for local politicians who are overworked and, you know, work part-time and all of that, to get up to speed, but also to just get everyone together in the community and say, ‘Where are we going and where do we want to go and how can we get there?’ And so, I think that’s probably the biggest thing. The only thing that would probably slow growth or make it more difficult would be like shutting down the airport [laughs]. But I’m not sure that’s going to happen, and I don’t advocate that in my book. But that would make an impact.

MACKIE: Will you continue to study Teton County?

FARRELL: I will, yup. I already have so many different projects and I have students doing their projects and I have a field course out here—one of the courses I teach at Yale is we actually come out here and the students meet with all different stakeholders and learn about different issues with the parks, with the town, everything. And so, yeah, I’ll be around for the foreseeable future.

MACKIE: Okay, great. Well, Justin Farrell, thank you so much for taking the time to chat with us at KHOL.

FARRELL: Great, thanks so much.