Tears dotted Jose Rivas’s cheeks as he watched his television screen. President Barack Obama was announcing a program to help him stay in the U.S. It was June 15, 2012, and Rivas, then 22, was at home nursing a serious injury. While he was working in the oil fields of Gillette, sheet metal sliced through his quad tendon. Rivas would undergo emergency surgery and months of physical therapy—the fear of medical debt weighing on his mind.

Normally such an injury would be covered by workers’ compensation. But under Wyoming law, undocumented workers like Rivas do not qualify for those benefits. Rivas hired a lawyer and a yearlong legal battle ensued that he ultimately won.

That day, he cried watching Obama speak because the immigration program, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, signaled a way to climb out of the shadows, out of a job where he had little recourse when things went wrong.

“They were tears of joy,” Rivas said.

Rivas, like many young people in the U.S., is still in a tug-of-war over his immigration status. In 2017, President Donald Trump tried to end DACA. The Supreme Court rejected that attempt in June. But advocates say the fate of DACA recipients still hangs in the balance—the reelection of Trump would likely mean the program will once again face litigation and this time a solidly conservative Supreme Court majority would have the final say.

Nearly eight years to the day that Obama announced DACA, Rivas, now 30, felt a similar jolt of emotion when the Supreme Court rejected Trump’s attempt to end the program. In a 5-4 decision, the high court ruled that the Trump administration unlawfully rescinded DACA in an “arbitrary and capricious” way.

The night before that ruling, after weeks of anxiety, Rivas knew the decision was imminent—word had been swirling through immigrant advocacy circles. Rivas went for a bike ride the next morning, pedaling past the Jackson National Fish Hatchery as rays of sunlight fractured through the clouds and glittered across the river. The scene was an omen.

“As cliche as it sounds, I knew at that moment we would get good news,” he said.

The good news spread fast. On his way home, Rivas’s cell phone erupted with text messages and phone calls from fellow DACA recipients in Teton County and across the state.

DACA has given roughly 650,000 young people brought to the U.S. as children a shot at a normal life in America. It does not present a path to citizenship, but the program has shielded them from deportation and cleared roadblocks so they can obtain driver’s licenses, work visas, and pursue higher education.

Rivas, who was brought to the U.S. by a family member when he was six years old, says DACA meant advancing his schooling. When Obama enacted the program, Rivas was taking a night class at Gillette Community College. After receiving DACA, he transferred to University of Wyoming and graduated at the top of his class with a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice.

It also meant giving back to his community through a new career. After he earned his bachelor’s, Rivas planned to go to law school and study immigration law.

But a job Rivas landed after graduation positioned him on a different path.

Rivas began working as a case manager in a group home for at-risk youth. He decided there that he could have a greater impact in a preventative role—helping young people before their problems escalated with law enforcement or attorneys. So he went back to school and earned a master’s in counseling. Today he works as a school counselor at Munger Mountain Elementary School as part of its dual immersion program.

“What better way than to catch troubled young people at an earlier stage in their life and do it through education?” Rivas said.

He views counseling as a way to build bridges with first-generation students, something that was missing from his time in school. Rivas’s school counselors did not understand the ramifications of being undocumented, he said, and the uncertain path undocumented young people confront after high school. Rosa Sanchez, a client services advocate at Community Safety Network, was walking that path.

“It was very disappointing to learn that no matter how hard I worked in school or other realms in my life, because I was undocumented I wouldn’t have the same results as someone who was,” the 26-year-old said.

After she graduated high school, Sanchez attended community college but she couldn’t work to support herself. Her status as an undocumented person precluded her from getting most jobs. Receiving DACA her freshman year was “life-changing,” she said. Sanchez was able to get a serving job to help pay for her tuition. DACA yielded the things that many of her peers do not think twice about: “a work permit, a social security card, and all the great stuff that comes along with that.”

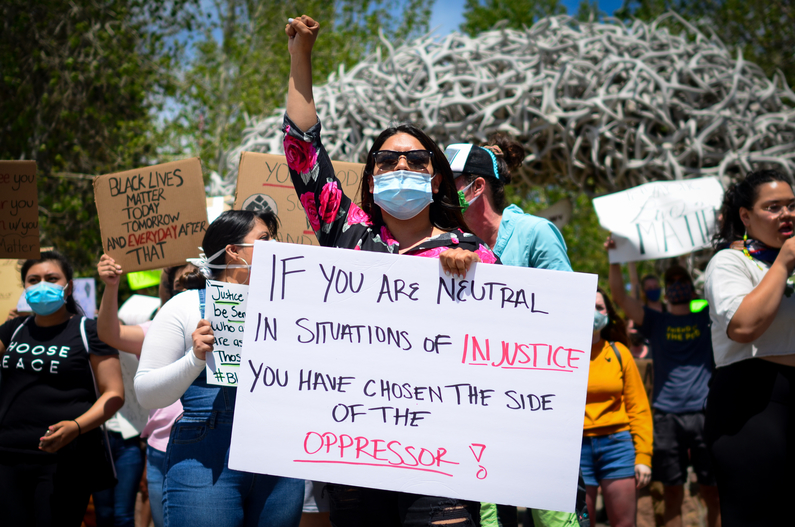

Rosa Sanchez at a Black Lives Matter rally in May. She came to the U.S. when she was seven years old, is a DACA recipient and college graduate. Today she works as an advocate at the Community Safety Network to give back to a community that has supported her, she said. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

Rivas said in addition to an uncertain path after high school, which forces young undocumented people into the shadows, his school counselors were also unfamiliar with the stigma that many in the Latinx community face accessing mental health services.

“Immigration, acculturation, trauma, and generational conflicts” compound that stigma, Mental Health America notes. The community-based nonprofit writes that the Latinx community faces “unique institutional and systemic barriers that may impede access to mental health services.”

Latinx children and adolescents, meanwhile, are at significant risk for mental health problems, and in many cases at greater risk than white children, according to the American Psychiatric Association.

Rivas says he is working to dismantle the stigma his students face.

A Lifetime of Anxiety

In 2019, more than 500 DACA recipients called Wyoming home. The Supreme Court’s decision touches many DACA recipients and their families in Teton County. Some are people like Rivas—school counselors. Others are social workers, nurses, educators, bankers and accountants.

DACA recipient Alejandra Jacobo, 24, is a nursing student at Central Wyoming College and a certified nursing assistant at St. John’s Health. She is among the roughly 30,000 healthcare workers in the U.S. who are DACA recipients. The Supreme Court’s decision, she said, opens a door that was closing before her eyes. Without DACA, Jacobo would be ineligible to obtain a nursing license after graduation. Now, amid her endless hours of homework, she has peace of mind. Her DACA status will allow her to take the six-hour nursing license exam and apply for nursing jobs. Yet she is in limbo, a sentiment that Jacobo traces back to her childhood.

When she was nine years old, Jacobo’s parents brought her from Mexico to the U.S. “It really started to affect me when I couldn’t get my driver’s license, I couldn’t apply for some scholarships, and I couldn’t get most jobs,” she said.

Jacobo grew up feeling anxious. Seeing police officers around town “was really scary,” she said. Now Jacobo harbors much of that same anxiety because she has trouble envisioning a permanent existence in the U.S. She constantly worries about school, life, work, her ability to travel, and the future. She dreams about home ownership, about entrenching her roots.

“But then it’s like, I don’t know if I’m going to be able to stay.”

DACA recipient Alejandra Jacobo, 24, is a nursing student at Central Wyoming College and a certified nursing assistant at St. John’s Health. The Supreme Court’s decision to reject President Donald Trump’s attempt to end DACA means she can take her nursing license exam after she graduates. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

Bianca Infante remembers a similar experience growing up in Jackson. When she was a sophomore in high school, she learned that to be undocumented was to live life on the sidelines. A driver’s license, scholarships, and part-time jobs were all out of reach for her too.

“That’s when I knew I had to protect myself more, and pretend that I was like everybody else,” Infante said.

After Infante received DACA, she attended the University of Wyoming and much of that fear dissolved. She met other DACA recipients and began speaking out about her experiences, addressing students for the university’s DACA symposium, an event where Rivas also opened up about being undocumented and receiving DACA.

Infante, the first person in her extended family to graduate from college, then utilized DACA’s “advance parole” program. It allowed DACA recipients to leave the U.S. for educational, humanitarian or employment purposes before it was suspended by the Trump administration in 2017. During an impactful trip to Mexico, she performed ethnographic research work and connected with family members.

“It made me want to do more. It made me want to be an advocate for everyone who has DACA status,” Infante said. Because even with DACA, “we still feel like we need to hide.”

Infante is focusing her master’s studies on immigration issues across the nation. For her thesis, she is studying the achievements of Wyoming’s DACA recipients. She is contrasting that with the experiences of young people who could not apply for DACA after the Trump administration rescinded it.

When the Supreme Court handed down its decision in June barring Trump from ending DACA, Infante was at the Laramie law firm where she is an intern, the Immigration Law Office of Travis Helm. She has been working there in preparation for her “overall goal”—to attend law school next fall and specialize in immigration law.

At the law firm that morning, Infante was in shock; she had been nervous since traveling to Washington D.C. in November 2019, when the Supreme Court heard arguments for ending DACA. She looked around the law office that day and saw tears streaking the face of her boss Helm. And reality set in—the grim prognosis for DACA had not been realized. She and the law office staff spent an hour and a half reading the Supreme Court opinion written by Chief Justice John Roberts, embracing, crying, talking.

Just a few days prior, Infante had submitted her DACA renewal form, uncertain if it would be the last time. Although the program has not accepted new applicants since 2017, current recipients have been able to submit applications to renew their status, which now expires every year—a change the Trump administration implemented after the Supreme Court’s decision. DACA recipients used to have a two-year window.

Infante says she is relieved that her renewal is safe for now, but she worries about other undocumented young people who did not meet the requirements to apply. And she knows her temporary legal status could be just that.

Bianca Infante is a graduate student at University of Wyoming who plans to attend law school next year. She is studying the achievements of Wyoming’s DACA recipients for her master’s thesis and comparing those experiences to young people who could not apply for the immigration program. (Courtesy photo)

Uncertainty Deepens Amid Supreme Court Appointment, Presidential Election

The hundreds of thousands of DACA recipients in the U.S. are known as “Dreamers,” a term that harks back to the 2001 DREAM (Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors) Act. Since the initial legislation was proposed, 10 versions of the act, which would have provided a pathway to citizenship for undocumented young people, have been introduced in Congress. Immigration advocates lament its long trajectory and near passage. The American Immigration Council notes that some iterations have drawn as many as 48 co-sponsors in the Senate and 152 in the House, but none has become law.

In 2010, the bill came closest to approval when it passed the House of Representatives but fell just five votes short of the 60 it needed in the Senate, AIC notes. Two years later, Obama stepped in and issued DACA by executive order to address Congress’s many failed bipartisan attempts to pass the measure.

Trump, meanwhile, campaigned in 2016 on a strong anti-immigration platform. It was no surprise when he rescinded DACA the following year. But since then he has flip-flopped about the immigration program. The president vowed to challenge the Supreme Court’s decision in June. Three weeks later he took a different stance. During a Telemundo interview, he said he would be signing a sweeping executive order that would include a road to citizenship for DACA recipients.

“It’s going to be a very big bill, a very good bill, a merit-based bill, and it will include DACA and I think people are going to be very happy,” Trump said in the July 10 interview.

The White House quickly walked back that announcement. “This does not include amnesty,” White House spokesman Judd Deere said in a statement.

The Supreme Court’s ruling, legal experts say, means the Trump administration must not only continue to accept renewal applications from people like Infante, Jacobo and Rivas, but it also must accept new DACA applications—something that has not happened since Trump ended the program in 2017. A federal judge recently reinforced that decision. Judge Paul Grimm of the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland said the program is to be restored to its “pre-September 5, 2017 status,” CNN reported.

New applicants, though, are still waiting.

On the heels of the high court’s recent decision, a number of local undocumented people have requested assistance filing their applications with Immigrant Hope, a local nonprofit that assists people in Wyoming and Idaho with DACA applications. “But everyone’s a little afraid to send it in,” Lori McCune, head of Immigrant Hope, told KHOL in July.

McCune said some of that fear stems from the price of the application. It costs $495 to file with United States Citizens and Immigration Services and there is no guarantee applicants will get that money back if their application is rejected. McCune said Immigrant Hope is providing funding for as many applicants as possible.

Immigrant Hope began encouraging people to renew their DACA applications ahead of the Supreme Court’s decision. Since then it has assisted dozens of young people in doing so. McCune says she also has had emotional phone calls and visits with undocumented folks who do not qualify for the program, typically because they fall outside of the required dates by as little as one to five months.

To qualify for DACA, applicants must have come to the U.S. when they were under the age of 16 and must have been under the age of 31 as of June 12, 2012. They must have continuously lived in the U.S. beginning June 15, 2007. Applicants must be in school, graduated from high school, obtained a GED or have been honorably discharged from the military.

McCune said even current DACA recipients are running into issues renewing their applications. “They desperately want it,” she said. “But they are either terrified of losing that money or they send it in and get some really weird answers back.”

She said the folks working at the USCIS offices “don’t quite have it together.”

McCune pointed to a recent application of a young woman who was applying for DACA renewal. USCIS, McCune said, sent back a confusing reply: 20 pages of receipts from the applicant’s 2018 application with no acknowledgment of the current renewal.

A Prideful, Fleeting Moment

Immigration attorney Elisabeth Trefonas works with potential DACA recipients in a number of ways. She represents young people, typically college graduates in their 30s who are employed full-time in Jackson. She also screens people to determine if they’re eligible; explains how they can apply and then sends them on their way; and she advises McCune at Immigrant Hope on how to proceed with applications.

Trefonas once offered informational DACA forums for potential applicants but turnout was low because young people feared attending the forums would make them a target for deportation, Trefonas said.

When the Supreme Court ruled in favor of DACA in June, Trefonas was stunned. The immigration attorney said she had always believed in Obama’s right to create the program via executive order and by extension, she knew it could also be dismantled with the stroke of a president’s pen. But, as she pondered the decision more she realized it was in keeping with a positive trend. Trefonas says the judicial system often tries to rule in ways that advance society despite its apparent insulation from politics and public opinion.

The ruling represents “a fairly technical way of getting to the right answer and courts “very much like to do that,” Trefonas told KHOL in July. “If they can rule on something in a way that gets us as a population where we should be, I think they try.”

Trefonas said with the two decisions handed down from the Supreme Court that week, recognizing the rights of LGBTQ people and upholding DACA, she had “never been more proud of being a lawyer or working in the judicial system.”

But since that ruling, the makeup of the high court has profoundly changed. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a fierce defender of equal rights, died in October at the age of 87, prompting Trump to hastily fill her seat before the November 3 general election.

The ideological opposite of Ginsburg, Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s appointment to the Supreme Court concerns immigrant rights advocates.

The Arizona Republic reported that Barrett has written decisions on three immigration-related cases. “Those decisions indicate Barrett could side with many of the Trump administration’s immigration policies facing legal challenges,” Daniel Gonzales writes.

Trump has signaled he will challenge the program again, which means it is likely to face future litigation. The DACA ruling was a narrow 5-4 decision with Roberts siding with the court’s liberal judges. Barrett, a darling of the conservative movement, could determine the next such ruling. In other words, there’s no guarantee the court will continue to advance society in the way Trefonas suggests.

Hence, whether Trump or former Vice President Joe Biden wins the presidential election could seal the fate of Dreamers. In sharp contrast to Trump, Biden says DACA recipients should be immediately granted citizenship. During the October 22 presidential debate, Biden acknowledged that many Dreamers may know very little about their home countries. They are Americans, through and through, he said.

“They’ve been here, many of them are model citizens, over 20,000 of them are first responders out there taking care of people during this crisis,” Biden said. “We owe them.”

Rivas, for his part, says he has always felt like a true American—and especially a Wyomingite. The state he has lived in for much of his childhood and his entire adult life has shaped who he is today.

“I always tell folks—‘I’m a Wyoming cowboy,’” Rivas said. “I’ve been through the community college system, I’ve been through University of Wyoming—bachelor’s, master’s.”

Rivas pointed to University of Wyoming’s motto: “Once a cowboy, always a cowboy.” He said that’s how he and many fellow DACA recipients in Wyoming see themselves.

“We’re cowboys, we’re Americans—heart, mind and soul,” Rivas said. “We just don’t have that paper that tells us we’re American.”