Rays of sunshine spilled from between the trees, painting shadow and light onto protesters. Their knees to the damp earth, some people raised their fists in the air. Others clasped their hands together, looked at the ground and prayed.

Hundreds of people kneeled at George Washington Memorial Park on Town Square Monday for eight minutes and 46 seconds, the time that Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin pinned George Floyd to the concrete while he called out for his mother.

Moments before, organizer Ellen Weddington addressed the crowd through a megaphone. She praised the community for showing up in large numbers and told them they were there to honor Floyd and all the other black Americans that died unjustly before him. “We’re here to say we’re not going to stand for that.”

Weddington urged people to educate themselves about “how we got to where we are today,” and encouraged them to keep the momentum going.

Ellen Weddington organized a Black Lives Matter demonstration on Monday that drew hundreds to Town Square. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

Weddington was resourceful in planning for one of Jackson’s biggest demonstrations in recent memory. She borrowed supplies from recent area rallies. She drove to Victor, Idaho, earlier that day to pick up the megaphone from Gregory Meyers, among the leaders of a Black Lives Matter march that drew roughly 300 people to Teton Valley on Saturday.

Weddington and friend Sage Lefkowitz, who are both white, handed out pamphlets that mirrored ones Weddington received at a protest in Pinedale last week. They prompted self-reflection for white folks, describing how to be allies to people of color, organizations to support, books to read, movies to watch, and a quiz that challenged white people to consider their privilege.

“Check all that apply,” the pamphlet instructed.

“I have never taken a job where coworkers suspected I was hired due to affirmative action.”

“I have never had someone lock their car door as I walk by.”

“I have never been followed and harassed while shopping.”

“I have never been treated harshly or unfairly by the police.”

Eight more experiences were listed, each exemplifying the ease with which white people move through America’s white spaces and the structural racism baked into different spheres and systems.

Lefkowitz said she has seen firsthand how people of color endure those examples of racism. In such instances, she has used her privilege as a white person to speak up. “But now it is time to be louder and make a change, a big change,” she said.

Wes Gardner and Meghan Warren brought their 11-week-old son Wren to his first protest that day. As a white man, Gardner said it was important for him to support the folks who are feeling “the trauma”—pain that is foreign to him.

“It’s just unacceptable that there are not only two systems of justice, but some of the arbiters of that justice are seeing us through different eyes when they’re dealing with me versus someone of color. That’s gotta stop and we have to do whatever we can to support that.”

Gardner wants swift government action. He was happy to see House Democrats release a police reform bill earlier that day. The word in the front of his mind right now: urgency. “With each one of these, another person dies. That’s very final and we can’t accept that any longer. This is a representative democracy, that means we’re the ones who control the policy and we have to hold ourselves accountable.”

The death of Floyd, an unarmed black man killed on May 25 while in police custody, has triggered a national uprising and sparked global demands for justice. His death has placed sustained focus on this country’s systemic racism and the disproportionate number of black people who die at the hands of police, prompting cities across the nation to examine their community’s policing practices and budgets.

“This is a representative democracy, that means we’re the ones who control the policy and we have to hold ourselves accountable.”

Lucy O’Connor, who is white, held a sign that read “defund the police.” O’Connor, 20, said she was encouraged to learn Minneapolis City Council was moving in a direction to do that. “I hope it creates some sort of ripple effect and that more communities start talking about it,” she said.

Lucy O’Connor holds a sign reading “Defund the police.” She said she hopes a national conversation about policing leads to deep reforms. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

Policing Under the Microscope

Protesters on Monday largely acknowledged Jackson does not have a history of police violence, something Jackson Chief of Police Todd Smith has readily pointed to in recent weeks. He told KHOL that in his 29 years on the force, police have never shot a citizen. In the last decade, he recalled two times officers have used a taser. In 2018, a female officer deployed hers to break up a fight at the Cowboy Bar during Hill Climb weekend. Five years prior, a female officer used a taser at the hospital. A person detained on a mental health hold there escaped from his room, obtained a knife and was “going around the hospital threatening people with it.”

“It would have been a deadly force situation to shoot him legally because he came at the officer with a knife,” Smith said. Instead, the officer opted to tase the man.

Smith and Teton County Sheriff Matt Carr follow a community policing model that contrasts policing in big cities and few have publicly taken issue with many of those policies. But some community members are challenging local policing as we know it amid national cries to defund or reimagine law enforcement. They want to redirect money away from the police department and sheriff’s office and into social services.

Jackson Town Council is set to approve its 2021 budget on June 15 and Teton County Board of County Commissioners at the end of the month. Ahead of those meetings, more than a dozen people have sent emails to officials about the police and sheriff budgets.

“I support reallocating the massive and unnecessary funding of our police and public safety institutions, instead devoting money to health, education, childcare, and food insecurity,” wrote Stuart Agnew in a June 4 email to elected officials. “These are absolutely the most vital services in our community, whose existence and impacts reach far beyond the need for overly funded law enforcement.”

“I support reallocating the massive and unnecessary funding of our police and public safety institutions, instead devoting money to health, education, childcare, and food insecurity.”

Mayor Pete Muldoon, for one, is engaging in this discussion. On June 6, he posted to his Facebook page an Atlantic article titled “Defund the Police”— with the caveat that Jackson’s police are nothing like the troubled officers in Minneapolis.

“We have a fine police force who do the job their town council asks them to do, and do it well,” Muldoon wrote. “This is a credit to the officers and to the police department leadership, and I know that if our officers had arrested George Floyd, he would be alive and well today.”

Still, he told KHOL it is a useful exercise to look at what falls under the umbrella of police work. Should law enforcement be in charge of parking or answering mental health calls, Muldoon asked.

Muldoon said Jackson Town Council’s first priority, however, is to review police use of force policies. “Community members are asking for this,” he said. The council will schedule a time for that during its June 15 meeting. Conversely, addressing police responsibilities will take time, Muldoon said. That conversation requires multiple folks at the table, from elected officials and town staff to law enforcement and social service providers, he said.

Smith said Jackson police follow all but one of the 8 Can’t Wait directives outlined by activists to reduce police violence. The “Use of Force Continuum,” Smith said, is outdated. It requires officers to follow a pyramid, meaning “when this happens you can do this, when this happens you can do this, and it pyramids up to a greater use of force.” Instead, his officers follow a policy of “reasonableness” per the 1989 Supreme Court case of Graham v. Connor. The Use of Force Continuum is about “what you can do,” Smith said, whereas “the reasonable officer approach is about what you should do.”

But the jury is out on Graham v. Connor, at least according to some. An opinion piece in the Washington Post argues the case is “unintentionally providing cover for police brutality.”

What role police should have in situations such as mental health crises is a good question, Smith said. The burden of addressing nuanced social issues has fallen on law enforcement, he said, filling “a need” in social services.

“I think the complex part of this is that police are arguably not experts about anything. They are a jack of all trades and they wear many hats. So sitting in an office on Monday morning, it looks good on paper to say, the cops shouldn’t do that, that’s not their job. So whose job is it?”

Smith said the use of force is often necessary when dealing with people who have mental health issues or are homeless.

“True transients, living in the bushes all year long, often suffer from mental illness or substance abuse issues. When they start doing something that people don’t like, are you going to call a counselor to go into the bushes at 3 o’clock in the morning or are the police going to go there first, make sure it’s safe for a counselor to go there and size it up? That’s the system in place throughout America.”

Some communities have found novel ways to limit the interactions that police have with folks suffering from mental health crises. NPR offers the example of Eugene, Oregon.

(Should the police’s role in Jackson shift? KHOL will be exploring this topic further. Stay tuned for that coverage.)

A New Image of Jackson

“Say his name!”

“George Floyd!”

Back on Town Square, protesters erupted into chants. “No justice, no peace, no racist police!”

Many older folks and families left after kneeling in silence, but a few hundred remained, assembling into groups on the four corners of Cache and Broadway. Occasionally they poured onto the street blocking traffic. Some laid face down on Cache.

Protesters blocking traffic on Cache and Broadway drew honks and fists of support from motorists stuck in a line the cars. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

A number of motorists responded in support, raising their fists and honking while a few disapproving pickup trucks revved their engines as they sped down Cache.

Police presence, meanwhile, was minimal. Jackson Sgt. Michelle Weber said Jackson Police had a few officers there “just to keep people safe.” One sheriff’s deputy attempted to redirect protesters from the street back to the sidewalk. For several minutes on Cache, protesters stood in front of the deputy’s car chanting, “No justice, no peace, no racist police.” The deputy opened his car door and asked the protesters to move from the street. They didn’t budge and he ultimately drove around them.

Near the antler arches, Malak Ghazal, a Palestinian American, launched into a chant that has perhaps never filled the streets of Jackson, a town with a tiny Arab American population: “Black lives matter! Free Palestine!”

The Moose resident later invoked Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” she said, drawing parallels between the oppression of black people in America and that of Palestinians in the Middle East. “The Black Lives Matter movement connects directly to the Free Palestine movement,” she said. “The militarization in the United States against its own civilians is directly related to the militarization of the United States abroad.”

The chanting morphed back to “Black Lives Matter” and one anxious moment unfolded soon after.

People’s attention shifted to the intersection of Cache and Broadway when a white man in a wheelchair got out of a car that was stopped on Cache. He confronted protesters that were blocking traffic and his sister, the driver, joined him.

Yaya Birch, an African American resident, said she approached the brother and sister to diffuse the situation. “I told them if they stepped back, we would move,” she said. In response, Birch said they yelled racist remarks at her.

The encounter was one reason Birch was protesting: “to show light to what has been in my life.”

Still, Birch does not paint racism in America with broad brushstrokes. She has long navigated life through a multicultural prism. Birch is adopted, has white parents, white siblings and grew up in Rexburg, Idaho, an area with few black people. “So, do I think all white people and all police are bad? No, I am in the middle. I just want peace. There is a problem and I feel like people are finally starting to realize it and I am here to fight.”

Afterward, the man called the police. His sister “initially claimed she was assaulted,” Weber said. Police, however, determined there was no physical altercation, “just a moment of chaos,” and the woman decided against filing a complaint.

Yaya Birch, left, attempted to diffuse a situation with two white people who were angry that protesters were blocking traffic. She said they responded to her with racist remarks. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

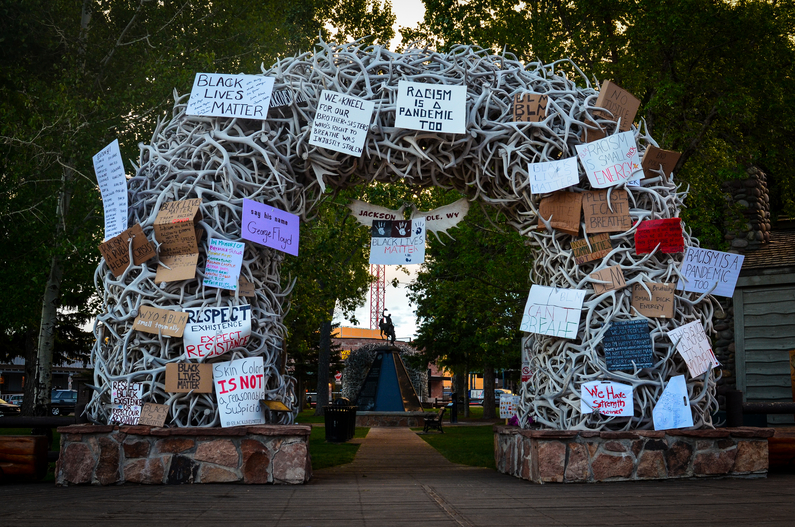

That tense moment was eclipsed, for some at least, when the elk antler arch on the southeast side of the square got a new look. People climbed the arch toward the end of the rally, affixing signs that read “Black Lives Matter,” “WYO for BLM” and “Racism is a pandemic too.”

Abraham Perez posed with a group of friends underneath the transformed arch. “Just like my sign reads, this isn’t a moment, it’s a movement,” Perez said. “This is not just a hashtag or a trend, it is something that needs to be reformed.”

Perez was struck watching an iconic Jackson Hole image shift before his eyes and display a message that felt modern, inclusive, and for the first time, directed at people like him. The 20-year-old came to Jackson from Mexico when he was eight and has sometimes struggled to find acceptance. “I’ve seen segregation here. I’ve seen it in school. I’ve seen it in the lunchroom of the cafeteria.”

He has experienced racism in the valley too, though Perez says it is more subtle here than in other places. “You get looked at a certain way, you get treated a certain way, just because of your skin color. They find out who you are and it’s, ‘Oh, he’s Mexican, an immigrant.’ You know, all these different names.”

Now, Perez says he is watching with pride as the community comes together, changes, awakens.

An iconic image of Jackson Hole was transformed but for a few hours on Monday. (Robyn Vincent/KHOL)

The elk antler arches did not bear the signs of an awakened populace for long, however. A few hours after the rally, a man named Tyler Van Sice can be seen in a video climbing the arches and plucking from the antlers each cardboard message demanding justice and decrying racism. Several bystanders angrily engaged and disparaged Van Sice. Why was he was removing the signs, they asked.

“Because all lives matter,” Van Sice said.

Passersby continued to press the man on his views, but he seemed more concerned about disposing of the signs. He didn’t want to leave litter behind, he said.

The cops were called shortly after about a person climbing the arches, according to Sgt. Weber. By the time police arrived, however, Van Sice was back on solid ground.

“It was just very disrespectful and ignorant,” said Josh Forman, among the bystanders demanding Van Sice stop tearing down signs on Monday evening.

KHOL contacted Van Sice but he declined to comment.

All Voices Heard

That someone tore down those messages of hope and equality was disappointing, said activist Luke Zender. He was thrilled on Monday when fellow protesters “finally found a use for the antlers.”

But he and fellow activists are hardly discouraged.

“Black voices in this community, all minority voices in this community, should be heard and that’s not happening. We need to strive to get to that point where we can have all of our voices heard.”

Zender and members of the newly formed group Teton People of Color and Allies talked logistics this week about a march they are organizing for Sunday at 4 p.m. It will begin at the Teton County Fairgrounds and end at Town Square. They are preparing for a massive crowd, setting up food and water stations and securing several speakers.

Zender and Tina Seay, who are both white, launched the group with two people of color, Jailyn Wallace and Koriann Arritt, to unify a rising movement. Zender said it is also the group’s goal to amplify the voices of people of color. He pointed to a Black Lives Matter demonstration he organized last week. Wallace and Arritt approached Zender there. They told him they hadn’t heard about the protest till moments before they showed up.

“I had gotten people together to protest Black Lives Matter, but we were not able to reach members of the local black community,” Zender said. He hopes the efforts of this collective have a broader reach.

Though the group is in its infancy, Wallace has identified a central goal: registering people of color to vote in 2020 and grooming them to run for office in 2022. The primary election filing period for local elections just closed with zero candidates of color throwing their hats in the ring. Meanwhile, there are no people of color sitting on Jackson Town Council or the Board of Teton County Commissioners.

Wallace wants to change that.

He said the onus is on white people to actively fight for racial justice and examine the ways they benefit from and perpetuate structural racism. But it is also important, he said, to position the voices of people of color at the center of this rising local movement and to help such folks have a voice in local decision making.

“Black voices in this community—all minority voices in this community—should be heard and that’s not happening. We need to strive to get to that point where we can have all of our voices heard.”