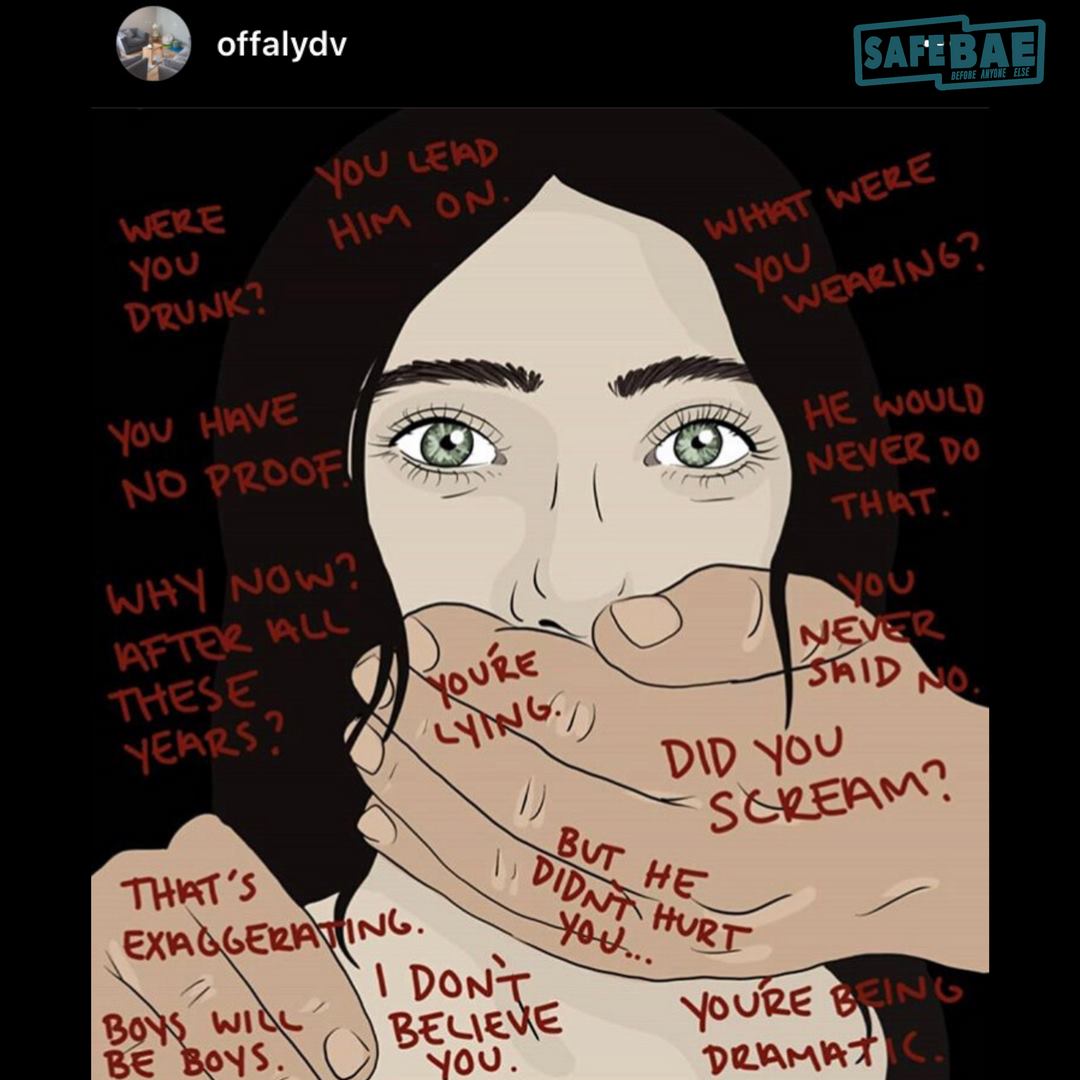

Ending sexual violence hinges on changing the culture of consent. That’s according Shael Norris of the nonprofit SafeBAE. She points to the problematic messages in television shows, movies and music videos. “The depiction of consent is so messed up on that level,” Norris said.

Young people are constantly seeing sexual situations where coercion and alcohol are normal ingredients. “And so they think, well, that’s OK. That’s not a big deal.”

Norris said it’s also important to remember that survivors often know their assailants. “We’re still taught in every way, shape and form that rapists are people who are strangers who jump out of bushes, hit you over the head and assault you. And that’s not actually the reality at all.”

Norris is the co-founder of SafeBAE. (BAE stands for “before anyone else.”) You may have guessed by the name that it’s geared toward young people. It is also largely run by them.

The mostly young members of SafeBAE speak at schools and events all over the country. They teach students about sexual violence, what it really looks like and what young people can do about it. They also advocate for consent-based education. That means teaching young people about consent that is mutual, ongoing, verbal, enthusiastic and sober.

The Community Safety Network and Teton County Family Planning are hosting members of SafeBAE this week in local schools. Dr. Karin Waidley, of the Community Safety Network, said SafeBAE checks all the boxes when it comes to effectively engaging young people. It’s youth-led, sustainable programming that is centered on peer-to-peer communication, Waidley said.

Since members of SafeBAE arrived in Jackson this week, Norris said she’s been encouraged by her interactions with Teton County students. Even with the problematic messaging that permeates pop culture, young people here and across the country are rejecting the narratives that downplay the value of consent, she said.

“My generation called it ‘a bad date’ and this generation is refusing to accept that,” Norris said.

Norris has long focused her career on advocacy. She is a founding staffer of V-Day, a global movement that is working to end sexual violence around the world. She was drawn to this work, “because I think I’m somebody who, in the face of injustice, gets very indignant. My motivation to be involved is by knowing people that this has happened to and wanting to be a part of change.”

“I don’t believe we can rely on survivors to change it for themselves,” she added.

“My generation called it ‘a bad date’

and this generation is refusing to accept that.”

Several of the other people who co-founded SafeBAE are survivors.

Daisy Coleman is one such person. Seven years ago, she was raped at the age of 14 in what became a highly publicized case out of Maryville, Missouri. She and a friend were partying with older high school boys who fed the young girls alcohol and assaulted them.

Coleman’s assailant left her outside her home, inebriated, on a frigid winter night. She woke up the next morning with her hair frozen to the ground. Her assailant came from a politically connected family and was never charged with assault.

After the night she was raped, Coleman’s life changed forever. Because she spoke out, Coleman was disbelieved, condemned and harassed. What she endured and how she survived is the subject of the 2016 documentary Audrie and Daisy.

Coleman said her work with SafeBAE has helped her to heal.

“There’s really been kind of this very specific path to my healing, which in the beginning I was obviously a victim and then I turned into a survivor.” Now, working with young people, giving them the courage to speak, Coleman is the healer, she said. “And I think that’s been the biggest portion of my progress.”

Sharing her story is also a way for Coleman to build bridges with survivors and non-survivors alike. “Whenever you’re talking to a survivor, you kind of see this moment of solidarity within the survivor,” she said. “But talking to someone who hasn’t experienced something like this and doesn’t know a lot about rape culture, I think it’s really kind of like an awakening for them.”

That solidifies the notion that there is a person behind the story, Coleman said.