When Arthur Carhart visited Trappers Lake in 1919, he was struck by the majesty of the Flat Tops mountains, the sounds of birds from stands of aspen and pine trees, and the crystal clear water of the lake: all of which you can still appreciate today.

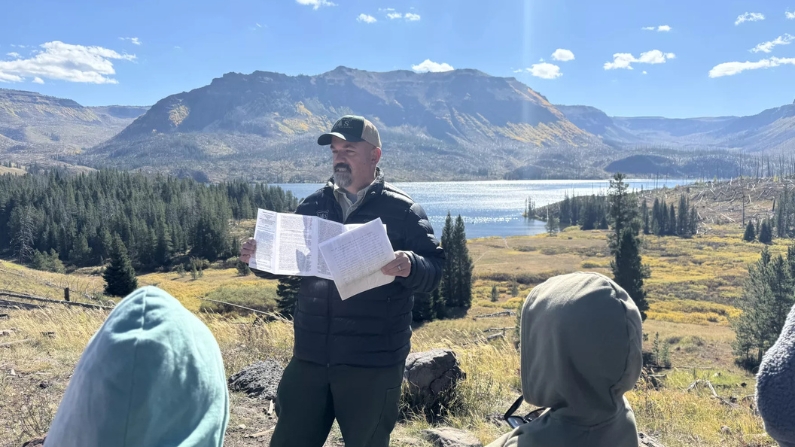

Curtis Keetch, the Blanco District Ranger for the White River National Forest, described Carhart’s reaction to the area.

“Just the wildness of Trappers Lake and the significance of how peaceful it was captured his soul, and really changed his mindset,” he said. “And he started to question, ‘do we really want to develop this?’”

Curtis Keetch holds a paper copy of the Wilderness Act of 1964, and shares with Meeker Elementary School students how the act helped to protect Trappers Lake, seen in the background. (Caroline Llanes / Aspen Public Radio)

Carhart was a landscape architect working for the Forest Service. He’d been sent up to the area, about 50 miles east of Meeker, on an assignment to make plans for roads, boat ramps, and summer homes on the lake.

“He felt that it was wild and it needed to stay wild for all the people to enjoy, not just the rich people that could buy a summer home, but all of us and not develop it, right?” Keetch said.

Carhart went back to Denver and told his supervisors he had a completely different concept for the area. Keetch explained that this is where the idea of wilderness was born.

“And because of that, Trappers Lake, this area is nicknamed ‘Cradle of Wilderness,’” he said.

It wasn’t until 45 years later that Congress passed the Wilderness Act, and it would be another 11 years before Trappers Lake itself was protected as part of the Flat Tops Wilderness.

This fall marks the 60th anniversary of the Wilderness Act, the law that gives Congress the authority to establish wilderness areas.

The act establishes that: (block quote here)

“A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

Decades later, land managers and advocates say it’s still a valuable tool to protect landscapes, and hope to expand its legacy.

“It provides a really high level of protection from extractive industries,” said Will Roush, executive director of Carbondale-based Wilderness Workshop. “So there’s no logging or mining or oil and gas development, no road building, no ski resort development in wilderness.”

Wilderness Workshop was actually founded shortly after the Wilderness Act became law to advocate for wilderness in the Roaring Fork watershed, areas that would become Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness, Hunter Fryingpan Wilderness, and Raggeds Wilderness.

There’s now hundreds of thousands of acres of wilderness in the watershed, and millions in western Colorado. Other wilderness areas near the Roaring Fork Valley include the Holy Cross Wilderness, the Eagle’s Nest Wilderness, and the Collegiate Peaks Wilderness.

“They took this new law and just ran with it,” Roush said of the group’s history. “And now, we’re the beneficiary of all that work to have all this wonderful wilderness surrounding us.”

Roush said wilderness areas also help build resilience against human-caused climate change.

They create clean air sheds, and are often areas for headwaters: water from Trappers Lake eventually feeds the Green River. Wilderness areas are also carbon sinks: they absorb more carbon than they release, storing it in soil, trees, and water sources.

As the pressure of human development in places like Aspen and the valley grows, they’re increasingly important for animals.

“It’s probably our best tool for protecting wildlife habitat, for protecting large areas of unfragmented lands, for the benefit of ecosystems and wildlife,” Roush said.

To that end, there are multiple bills in Congress to designate more wilderness in Colorado, and over 80 lawmakers have sponsored a bill to create Red Rock Wilderness in Utah.

But Roush said there are limitations to creating wilderness areas. He said one glaring error is the idea that these landscapes were completely devoid of people.

“There’s millennia of people living in all these places that are now public lands and that we’re protecting, and that they were home, and not like a recreational experience,” he said. “And so that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t keep protecting wilderness, but it means we need to really tell that story.”

Back at Trappers Lake, a group of fifth graders from Meeker Elementary got to learn that story on an annual field trip. Cate Blanch, the wilderness trails lead for the White River National Forest, explained to the students that it preserves a specific kind of feeling and experience.

Cate Blanch (left) demonstrates how to use an antique crosscut saw to a class of fifth graders from Meeker Elementary School. Caroline Llanes / Aspen Public Radio)

“What are you guys hearing?” Blanch asked the students.

Birds, chipmunks, and the lake were all answers provided.

“Yeah. You’re hearing these natural sounds, right? What are you not hearing?”

The kids sound off again: People. Electric stuff. Cars. Trucks.

“Beep beep,” one student said.

“Yeah. You’re not hearing all these sounds that humans make, right?” Blanch said.

Trappers Lake is often called the “Cradle of Wilderness,” because it’s where the idea of wilderness in America was born. It’s located in the Flat Tops Wilderness Area of the White River National Forest. (Caroline Llanes / Aspen Public Radio)

For Blanch personally, wilderness is a very nourishing, spiritual experience.

“What we’re looking at right now, this clean air, beautiful fresh water that you can see to the bottom of majestic mountains,” she said. “The solitude experience and listening to that sound of the wind, it’s incredibly difficult, especially in the modern area, to even be able to experience something like that.”

It’s all part of Arthur Carhart’s original vision to have places where anyone can enjoy nature at its most wild.

Curtis Keetch, the Blanco District Ranger, said he thinks it was ahead of its time.

“To me it’s, it’s impressive that he had the foresight and the courage to step up and start, you know, to push for that,” he said.

It’s a legacy that Colorado kids are still enjoying over a century later.